Locked away from society and at the end of the criminal justice chain, detention centres and prisons in many countries are vulnerable to corruption.54cc4e3404b7 Incentives to bribe prison officials for basic amenities, visiting rights, or early release are high, while external scrutiny is low.9d6434427df0 A driving factor is the overcrowding of many prison systems. According to Penal Reform International, overcrowding ‘undermines the ability of prison systems to meet basic human needs, such as healthcare, food, and accommodation’.9de68c1922e2 In this environment, competition for scarce resources increases corruption pressures on both prisoners and corrections personnel.6902022e39d8

Indonesia’s prison system faces severe overcrowding. As of December 2024, there were 273,495 people in prison nationwide, spread across 526 institutions with a total capacity of 145,699.a01a188241ef About a fifth of prisoners are pre-trial detainees. On average, Indonesian prisons and detention centres are at about 190% of their capacity, with some prisons in Riau and North Sumatra provinces reported to be between 300% and 800% of capacity.91452a20796c The ratio of prison personnel to prisoners was reportedly 1 to 53 on average in 2022.67765db08d93

In a 2018 study, theIndonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK)found that many detainees and prisoners overstayed their detention period and sentences due to an inefficient use of administrative discretion. Overstays add to overcrowding and cost the state an estimated IDR 12.4 billion (approximately EUR 750,000) per month. This brings them within the remit of the KPK, as losses to the state are an important element in establishing an act of criminal corruption in Indonesia.d3ccdbb695eb The KPK also found corruption risks in the placement of different types of prisoners across facilities; weak check-and-balance mechanisms in granting remissions; vulnerabilities in prison data management systems; and irregularities in food supply management, such as non-transparent vendor selection and mismanagement of funds, leading to scanty or poor-quality meals for prisoners.

In 2021, KPK found that 96% of its recommended actions had been implemented.aa3f1db5746f However, corruption in Indonesian detention centres and prisons remains a reality, one to which KPK’s own detention centre succumbed.f779b5c0264a No survey or comprehensive analysis has been conducted to quantify the extent of corruption in Indonesian prisons. This is not uncommon across prison systems, as all actors involved in corruption have incentives to conceal it, and prison facilities are physically walled off from public scrutiny.fb5745b7084d There is, however, plentiful anecdotal evidence on the various means by which corruption occurs in prison settings.22a5ac538062

For this brief, U4 collaborated with the Center for Detention Studies in Jakarta to learn more about corruption prevention efforts in Indonesian prisons. We focus on the emergence of so-called Integrity Zones, categorised into Corruption-free Zones (Wilayah Bebas dari Korupsi, WBK) and Clean and Service-oriented Bureaucratic Zones (Wilayah Birokrasi Bersih dan Melayani, WBBM). Both form part of Indonesia’s Grand Design of Bureaucratic Reform 2010–2025.

In October 2024, we conducted ten interviews with officials from the Directorate General of Corrections; officials of three prisons, two in Jakarta and one in West Java; and members of the National Assessment Team of the Ministry of Administrative and Bureaucratic Reform. One of the Jakarta prisons is certified as WBK, and the one in Cibinong, West Java, holds the higher-level WBBM certification. In semi-structured interviews, we enquired about the types of corruption prevention interventions that were undertaken as part of the efforts to have these two prisons certified as Integrity Zones.

In the following sections, we first provide a brief overview of the Indonesian corrections system. We then describe the process for certification of facilities as Integrity Zones, looking at specific initiatives to reduce corruption and improve services in the two certified prisons where we conducted interviews. While certification has led to some local reforms and innovations, there has been no systematic and transparent evaluation of their impact. We conclude that more transparency and collaboration with external actors could help monitor evolving corruption risks and progress towards reform at a time of government budget cuts. Ultimately, broader reforms of the criminal justice system are needed to address the drivers of prison overcrowding and its associated corruption risks.

The Indonesian prison system

Until November 2024, prisons in Indonesia were under the Ministry of Law and Human Rights, specifically under its Directorate General of Corrections (DGC) and its Regional Office (Kantor Wilayah). The DGC formulates corrections policy. The Regional Office coordinates operational implementation by Technical Implementation Units (UPT) in areas such as procurement. Both entities have the task of carrying out technical guidance and supervision, monitoring, evaluation, and reporting on correctional facilities.

As of late 2024, Indonesia had 526 prisons across its 38 provinces. Some of them contain detention centres for individuals who have been indicted for a crime but have not yet received a verdict. The total number of such detention centres cannot be confirmed, as the police, public prosecution offices, the KPK, the National Counter Terrorism Agency, and the National Narcotics Agency all run their own detention centres with their own procedures.Each centre is supposed to be registered with a prison, but the actual number remains uncertain, and monitoring by the Directorate General of Corrections has been difficult.

The splitting of the Ministry of Law and Human Rights into a Ministry of Law, a Ministry of Human Rights, and a Ministry of Immigration and Corrections in late 2024 led to further structural changes.9c6e653e505f The new Minister of Immigration and Corrections has created two new directorates under the DGC: a Directorate on the Corrections System and Strategy and a Directorate on Internal Compliance. The latter has the role of preventing corruption, managing gratuities, and monitoring the implementation of Integrity Zones. By the end of 2024, about 24% of Indonesian prisons were considered Integrity Zones.

Integrity Zones: 128 prison units certified

In the period from 2018 to 2023, 128 units in the corrections system were certified as Integrity Zones.832dd344bbd3 Of these, 122 obtained Corruption-free Zone (WBK) status. Six units were designated as Clean and Service-oriented Bureaucratic Zones (WBBM), requiring a higher level of innovation in the management of performance, integrity, and service, along with an ‘unqualified opinion’ from the Indonesian Audit Board.

Figure 1: Map of certified prison units by the end of 2023

Certified integrity zones across Indonesia’s prison system, with 122 facilities recognised as Corruption-free Zones (WBK) and 6 as Clean and Service-oriented Bureaucratic Zones (WBBM).

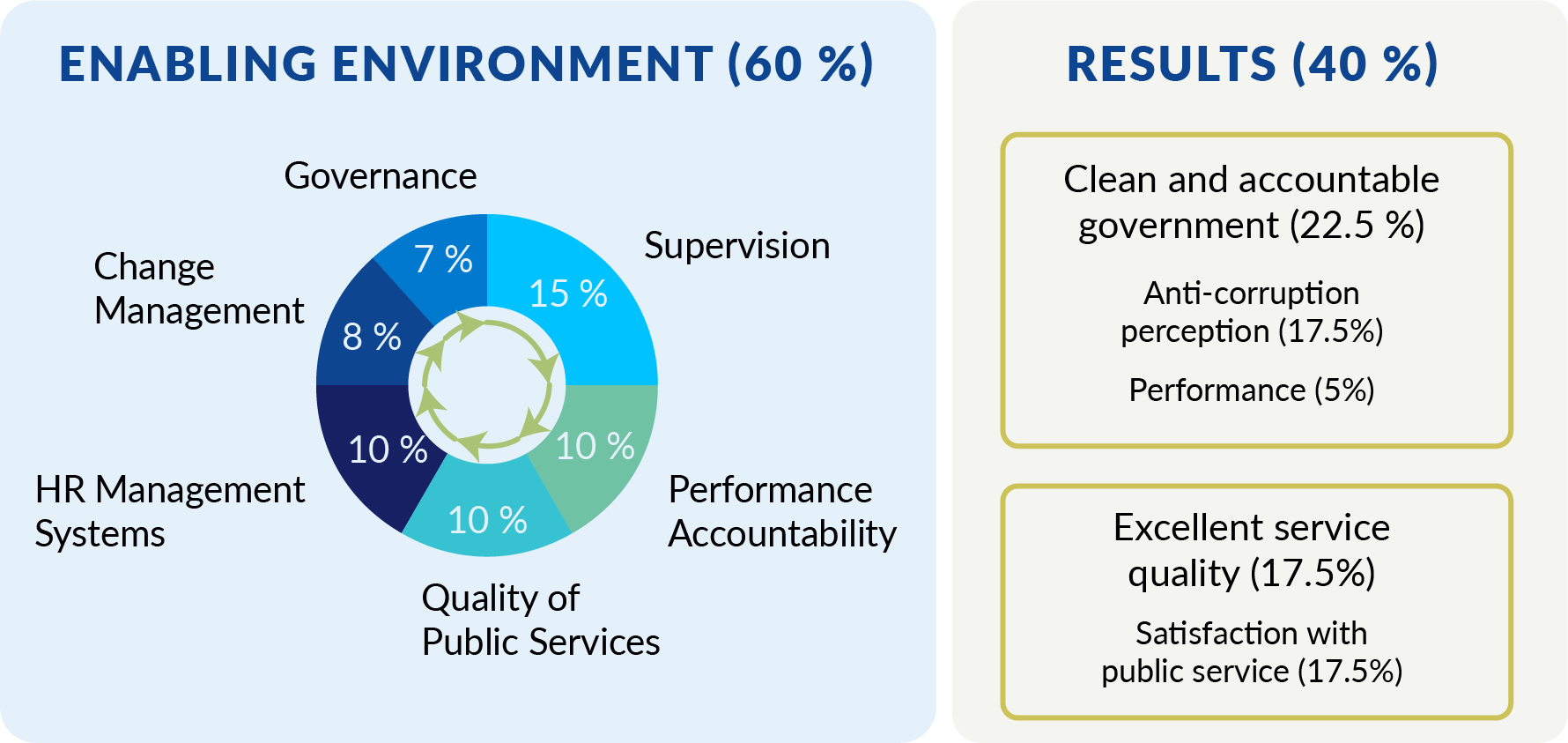

Certification as an Integrity Zone is based not on an evaluation of corruption levels in a prison, but on bureaucratic measures it has taken to reduce the likelihood of corruption, such as the provision of clear and transparent guidelines and the digitalisation of processes. An Internal Assessment Team (Tim Penilai Internal) and a National Assessment Team (Tim Penilai Nasional) evaluate improvements in the enabling environment (60% of the score) and results (40%). These assessment teams can also withdraw certification.a7cd641ed6d0 Figure 2 shows the assessment components.

Figure 2: Components of Integrity Zone assessments

The assessment examines six areas of change: change management, governance, human resources management systems, supervision, performance accountability, and quality of public services. These components of reform are expected to contribute towards two broad results: clean and accountable government, with targets based on anti-corruption perception and performance indicators, and excellent public service quality, for which a public satisfaction indicator is used. Since 2023 the units themselves are required to conduct these assessments using a standard methodology, under the guidance and supervision of the Ministry of Administrative and Bureaucratic Reform. To obtain WBK or WBBM status, a unit must score 3.6 or above on a 4-point scale of corruption perceptions, thereby reaching at least 15.75% under the corruption perception component.08f38c76ad31 Unfortunately, survey results are not made public.

In the context of corrections, the implementation of Integrity Zones depends entirely upon the initiative and responsibility of the relevant unit. The assessment is done upon application by an Internal Assessment Team (Tim Penilai Internal), which is formed by the head of the respective government agency – in this case, the Inspectorate General of the Ministry – to conduct assessments and provide recommendations to units that are currently building Integrity Zones. Only units applying for WBBM status have been assessed by the National Assessment Team, reportedly due to capacity constraints at national level.

Our research team carried out four interviews with officials of three different prisons, of which one is certified as WBK and one as WBBM; the third is not yet certified. These interviews revealed that a variety of small changes and innovations, many supported by digital tools, have taken place. However, it was impossible within the scope of this study to assess whether these measures have indeed reduced corruption. An official of Jakarta Women’s Prison suggested that when employees are required to fill out documents and provide supporting data, they become more accountable, aware that they should not carry out their duties without creating records that can serve as evidence of responsibility. However, if such changes are being systematically captured, the results are not publicly shared. Beyond the overall certification framework, which is outlined in the ministerial decrees, the assessment criteria and survey methodology are difficult to access in detail. Neither the results of surveys nor the overall assessments have been published.

Two examples of certified prisons are described in Boxes 1 and 2.

Box 1: Jakarta Women’s Prison – WBK certification

Indonesia’s female prison population has made up around 5% of the general prison population for the past decade.5c9c63f0b723 Jakarta Women’s Prison, established in 2017, held about 320 inmates in December 2024, about half of whom were incarcerated for drug-related offenses. After a visit to Semarang Prison, which already had the Corruption-free Zone status, the management of the women’s prison undertook efforts to achieve certification, which was granted in 2020.

The main steps taken by the women’s prison to become certified were as follows:

- Doubling of staff, from 50 to 100 employees.

- Development of various standard operating procedures.

- Emphasis on keeping records and receipts.

- Improvement of facilities, in particular the visiting area.

- Establishment of an electronic cashless system that keeps a record of transactions.

- Creation of an information system on WhatsApp, known as SiGawat (Sistem Informasi Keluarga Lewat WhatsApp), which prison officials and prisoners’ family members can use for updates and complaints.

Box 2: Cibinong Prison – WBBM certification

The prison in Cibinong, near Bogor in West Java, is one of six in Indonesia that held WBBM status at the end of 2024. It is classified as an IIA prison, meaning that it has medium-level security and facilities. At the beginning of 2025, Cibinong Prison housed 1,950 men, of whom about 360 were in pre-trial detention. The large majority of prisoners are serving sentences longer than one year.

Cibinong Prison obtained WBK status in 2018 and WBBM status, the highest level of certification, in 2020. The innovations that gained it this status include:

- Improvement of the visitor entry-exit system to reduce the smuggling of illegal items.

- Installation of air conditioning to enhance comfort in the visiting area.

- Digitalisation of visitor registration to reduce congestion and waiting times.

- Training of officers on customer service, by learning from several major state-owned enterprises in Indonesia.

- Creation of a fingerprint-access system that provides information about a prisoner’s sentence. Prisoners and their families can use the system to learn when parole and other rights can be obtained, and when the prisoner will be released. This can help reduce the potential for extortion by rogue officers.

- Recording of donations, including those made under corporate social responsibility schemes. These are then reported to the Ministry of Finance through the Financial Application System at Agency Level (SAKTI).

- Creation of complaint channels for visitors through SmartPASS, WhatsApp, and the social media of Cibinong Prison.

- Public service satisfaction surveys, which are regularly updated on the prison’s social media.

Beyond the scope of these individual prisons’ initiatives and the institutional risks identified by the KPK study, broader criminal justice policy reform is required to address the overarching challenge of overcrowding and its resulting ills, including corruption.

Drivers of overcapacity and corruption

While reforms in individual prisons are encouraging, they will be limited in their impact unless key drivers of corruption throughout the prison system, most notably overcrowding, are addressed.

Reforms in criminal justice policy after the end of the Soeharto regime followed a ‘tough on crime’ paradigm, almost doubling the number of criminal offences by turning previously administrative sanctions into criminal ones. In 2009 a range of new, overlapping drug-related offences with mandatory minimum sentencing were introduced. These have left a great deal of discretion with police and prosecutors on what charges to bring, increasing incentives for bribery. An offender may offer, or be asked for, a bribe to induce law enforcement personnel to opt for a lesser charge with a lower sentence.bd9d7f7075b4

Excessive use of pre-trial detention, from the time of a person’s arrest to the beginning of a court hearing, is a main cause of overcrowding in Indonesian prisons. About 21 percent of prisoners in Indonesia are in pre-trial detention, many of them housed in regular prisons due to a lack of separate detention facilities. No court warrant is needed for the first 90 days of detention after arrest, and pre-trial detention can be extended to a total of110 days.Once court procedures begin, judges may extend detention throughout the trial, appeal, and cassation stages, up to a maximum of 400 days before the final court decision is issued.7cfd71b1b908

The current Criminal Procedure Code allows accused persons to challenge an arrest or detention through pre-trial hearings, but the process is difficult and expensive for poor and marginalised people. By law, free legal representation must be offered to those who cannot afford it, but in practice many detainees forfeit that right. The main reason is reportedly detainees’ concerns about delay, as eligibility for free aid needs to be proven, and both local law enforcement budgets and the number of attorneys outside urban centres are very limited.56d153508f00

Official reasons for the use of pre-trial detention include the need to avoid evidence tampering, repeat offences, or the disappearance of suspects.94c790a6931d Reported reasons for the excessive use of pre-trial detention are punitive sentiment among law enforcement personnel, convenient access to accused persons, and performance metrics.258fbc491015 Some observers also allege that law enforcement agents use detention deliberately as a means to extract bribes from desperate detainees and their families.

Further action to prevent corruption in Indonesia’s prison system

Correctional institutions are just one part of the criminal justice chain. Corruption in prisons cannot be addressed without taking into account the criminal justice paradigm and the overall law enforcement process.

Reduction of overcrowding through non-custodial sentencing and rehabilitation schemes

The new Criminal Code enacted at the beginning of 2023 will enter into force in 2026. Although the new code imposes restrictions on civil liberties,062c646d4f58 it expands sentencing options from death sentence, imprisonment, and fines to include other non-custodial sentences that may be more conducive to rehabilitation, such as community service and probation. This is an important step that can reduce the influx of detainees into the prison system, thereby reducing prison overcrowding and the pressure to bribe.

In November 2024, the newly appointed Coordinating Minister for Law, Human Rights, Immigration and Correctional Institutions, Yusril Ihza Mahendra, acknowledged the urgent need to address overcrowding. In particular, the government seeks a more rehabilitative approach to drug users. In 2024, about 50% of all detainees in Indonesia were incarcerated for drug-related offences.c07c3f72e92e

In addition to preventing an excessive inflow of detainees and prisoners, an equally important means to reduce overcrowding is to ensure a more efficient outflow of prisoners. Reformers for years have recommended investing in accelerated and increased assimilation, particularly of juvenile prisoners, in half-way houses, in religious and social institutions, and in work and training programmes outside prisons during the day.56cafdec24cf

More accountability in the pre-trial detention process

Changes to the detention process could limit the number of pre-trial detainees and help reduce prison overcrowding, thereby addressing one of the enabling factors of prison corruption. Reformers are demanding amendment of the Criminal Procedure Code to improve accountability in pre-trial detention. The reform process should explore the feasibility of introducing a preliminary hearing session in front of a judge before police are permitted to detain a suspect, ideally with legal representation made available to all.fa9ae9b36885 Different drafts of a proposed new Criminal Procedure Code have been developed and are expected to be deliberated in Parliament during the 2025–2029 legislative period.

Stocktaking and evaluation of bureaucratic innovations

The creation of Corruption-free Zones in selected correctional facilities is an important innovation that other correctional institutions, within and outside Indonesia, could potentially learn from. However, for that to happen, the certification system needs to become more transparent so that assessments can be verified or corrected by independent reviews.

The establishment of a new Ministry of Immigration and Corrections and the approaching end of the Grand Design of Bureaucratic Reform 2010–2025 should prompt a review of efforts so far. A stocktaking of the results of Integrity Zone certification, if not a fully-fledged independent evaluation, could inform the design of a next phase of reforms.

For the corrections system in particular it would be timely to assess the impact of certification and the innovations it has brought, such as the introduction of a plethora of digital tools, before scaling up. Which of these are working well and could be rolled out across the corrections system? Currently, the drive for innovation comes at the cost of standardisation and equal treatment. For example, some prisons, but not all, are using different cashless systems and communication platforms for interaction between prison officials, prisoners, and their families. Innovations have blossomed, but they should not be left unattended. Those best adapted to the prison environment and its risks should be identified and propagated.

More transparency and collaboration with external actors

Lastly, it is high time that Indonesian prisons follow good practices in other countries by opening their gates to external oversight to allow for external monitoring and verification.cfc42978d0b7 Collaboration with external monitoring bodies seems particularly pertinent in light of recent budget cuts. A new scheme launched by the President in February 2025 to provide free lunches to high school students has led to severe cutbacks in other areas. The 2025 budget of the DGC was cut by about 33%, from IDR 9 trillion (528 million EUR) to IDR 6 trillion (352 million EUR). According to DGC officials, savings will be made on office stationery, official travel, and meetings and events outside the government’s office. A side effect of this will be the replacement of much of the onsite monitoring of prisons with online monitoring.

Previous collaboration between the Ombudsman Office, the National Commission on Human Rights, the National Commission on Violence Against Women, and the Directorate General of Corrections on the prevention of torture has included some prison monitoring. This monitoring should be revitalised and extended to include relevant civil society organisations.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2013.

- Penal Reform International 2025.

- Messick and Schütte 2015.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2017.

- Budi 2022. More recent data could not be obtained from the Directorate General of Corrections.

- Guritno and Asril 2023. For an up-to-date account see the database of the Directorate General of Corrections.

- World Prison Brief data on Indonesia, accessed 2 December 2024.

- KPK 2018.

- Purwaningsih 2018; Indonesia Corruption Watch 2018.

- Hill 2015.

- Tim Kompas 2024.

- KPK 2021, p. 5. Unfortunately, these studies conducted by KPK have not been published in their entirety, unlike KPK reports on other topics, but recommendations and progress on implementation of the actions were shared in press conferences. See, for example, Fadhil 2019; CNN Indonesia 2020; Ni’am and Setuningsih 2023.

- The number of ministries and resulting cabinet posts was increased from four coordinating ministers and 34 ministers in the previous administration to seven coordinating ministers and 41 ministers in the ‘Red-White Cabinet’ to accommodate a large political coalition under President Prabowo.

- Technical units can be detention centres, prisons, parole-probation offices, and storage houses for goods confiscated by the state.

- In 2021 five units in the corrections system reportedly lost their WBK certification (Kementerian Imigrasi dan Pemasyarakatan Republik Indonesia, Direktorat Jenderal Pemasyarakatan 2021). While the exact reasons in these cases are unknown to the researchers, we know that in other parts of government certification was withdrawn when bribery and extortion cases were being investigated in the relevant unit. See Kementerian Pendayagunaan Aparatur Negara Dan Reformasi Birokrasi 2022.

- Regulation of the Minister of Administrative Reform and Bureaucratic Reform No. 90/2021 on the development and evaluation of Integrity Zones towards Corruption-free and Clean and Service-oriented Bureaucratic Zones.

- Sudaryono 2021; KPK 2018.

- Kementerian Imigrasi dan Pemasyarakatan Republik Indonesia. Direktorat Jenderal Pemasyarakatan 2023.

- Situmorang 2011; Collins, Trisia, and Oktaviani 2021.

- Sudaryono (2021) describes how the need for increased budgets (based on the previous year’s records) leads to setting ever higher targets for the number of criminal cases successfully referred to the prosecutor.

- Sudaryono 2021; KPK 2018.

- Butt 2023.

- Of those imprisoned on drug offenses, 36 percent are classified as users, not dealers, though some may in fact be both. TVonenews 2024.

- For examples, see Center for Detention Studies and Indonesian Directorate General of Corrections 2024; Indriana and Maulana 2021.

- Kusadrianto 2019.

- Penal Reform International and U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre 2024.

- World Prison Brief data on Indonesia, accessed 5 December 2024.