Query

Please provide an overview of corruption and anti-corruption in Sudan, with a focus on corruption risks in agriculture, energy and environment, and obstacles that sustainability initiatives in these sectors are facing.

Background

Sudan gained independence in 1956 after over a hundred years of British colonial rule (Al-Shabi and Collins 2025; The Enough Project 2017:3). Since then, the country has experienced several periods of dictatorships, including from 1958-1964, 1969-1985, and 1989-2019 (Abbashar 2023). The longest rule was that of Omar al-Bashir, who remained in power for three decades. During his tenure, al-Bashir, alongside the National Congress Party (NCP), established a ‘centralised kleptocracy’ in which state resources were allocated to his cronies, family members and security agencies (Sudan Armed Forces – SAF – the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces – RSF382f195a7ea0 – and the National Intelligence and Security Services – NISS) at the expense of the public interest (De Waal 2019; Osman and Salih 2024).

Upon taking power in 1989, al-Bashir dismantled trade unions and professional associations, and purged non-Islamists from the officer corps (De Waal 2019). His regime was characterised by state capture and the co-optation of institutions, enabling a small elite to profit by instrumentalising institutions to loot resources, ensure impunity for corruption, and facilitate political repression and state violence (The Enough Project 2017). In parts of the literature, al-Bashir’s regime is described as a ‘violent kleptocracy’, defined as:

‘a system of state capture in which ruling networks and commercial partners hijack governing institutions for the purpose of resource extraction and for the security of the regime. Ruling networks utilise varying levels of violence to maintain power and repress dissenting voices. Terrorist organisations, militias, and rebel groups can also control territory in a similar manner’ (Menkhaus and Prendergast 2016).

Al-Bashir’s rule was also marked by the civil war in the Darfur region of Sudan, during which at least 300,000 people were killed in the conflict between rebel groups and government forces (BBC 2021). In 2009, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant against al-Bashir for war crimes (BBC 2021).

South Sudan’s vote for independence from Sudan in 2011 took a toll on Sudan’s economy as the country lost 75% of its oil reserves (The Enough Project 2017:12). As a result, oil revenues declined from approximately US$11 billion in 2010 to less than US$1.8 billion in 2012 (The Enough Project 2017:24). Since oil exports served as the main source of foreign currency, which paid for food and other imports, Sudan lost 95% of its foreign currency in the immediate aftermath of secession (The Enough Project 2017:24).

Sudan’s economic crisis intensified from mid-2017, despite the removal of US economic and trade sanctions in October of that year (Baldo 2018). In response, the government introduced austerity measures and a sharp currency devaluation in December 2018 and implemented cuts to bread and fuel subsidies (BBC 2019a). These actions triggered protests in the east that quickly spread across the country (BBC 2019a). Following months of mass protests by a civilian protest movement against poverty, kleptocracy and cronyism, the leaders of military, security and militia formations overthrew al-Bashir in a palace coup in April 2019, effectively ending his 30-year long rule (De Waal 2019; Abbashar 2023; Al Jazeera 2024).

In December 2019, al-Bashir was sentenced to two years in detention on corruption charges for receiving illegal gifts and possessing foreign currency. During the trial, it was revealed that he had admitted to receiving US$25 million in cash from Saudi Arabia for personal use (Burke 2019; Al Jazeera 2019).

Following his removal, protesters demanded the dismissal of his military loyalists and the establishment of civilian rule and democracy. However, in June 2019, security forces including the RSF, SAF and police violently dispersed a sit-in protest in Khartoum, firing on unarmed protesters, killing scores and injuring hundreds (assistant researcher and Henry 2019; Al Jazeera 2024).

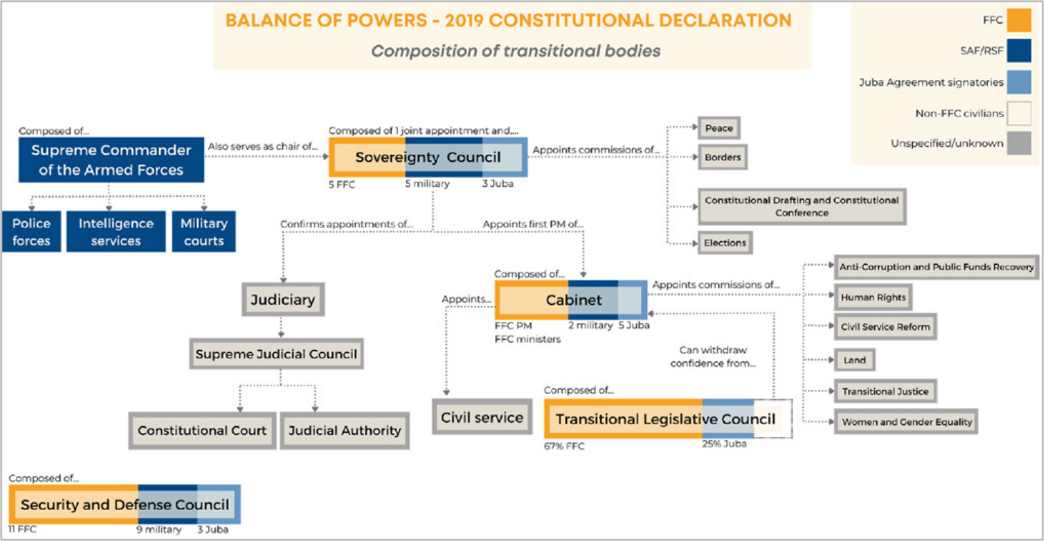

In August 2019, the civilian opposition, under the umbrella of the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC), signed an agreement with the transitional military council (TMC) to form a transitional government (Davies 2019; Abbashar 2023). As part of this process, the parties adopted a draft constitutional charter, which replaced the 2005 interim constitution. Prior to that, they had reached a political agreement intended to guide the country through the transitional period (Davies 2019). The agreement established a power-sharing arrangement between the FFC and TMC, and the first negotiated document was the July 2019 political agreement, which outlined the formation of three main branches of the transitional government: a sovereignty council,1e827e735c05 a council of ministers53a894ef018b and a legislative council0dd4459855b0 (Davies 2019: 11). The draft constitutional charter, signed in August 2019, elaborated on this structure and included provisions on the transitional form of government (detailing the powers of the three main bodies defined in the political agreement), oversight institutions (e.g. the public prosecutor) and a list of independent commissions, among other elements (Davies 2019: 12).

Figure 1: The balance of power according to the 2019 constitutional declaration and its amendments.

Source: Davies 2019: 17.

The constitutional declaration was amended shortly thereafter, following the October 2020 Juba Agreement for Peace in Sudan, signed between the transitional government and a series of armed groups. This agreement resulted in changes to the composition of the three main governing bodies, sovereignty council, the cabinet and the legislative councild3edc3b07222 (Davies 2019: 19) (Figure 1).

However, just two years after the signing of the constitutional declaration, in October 2021, the SAF and RSF jointly orchestrated a coup. They detained the prime minister Abdalla Hamdok and suspended key provisions of the 2019 constitutional declaration, including those establishing the sovereignty council and the transitional cabinet. These actions were justified by claims of a political deadlock and a worsening economic crisis (Center for Preventive Action 2025).

After several weeks, the military reinstated Hamdok and reconstituted the government based on a later agreement, a move that sparked widespread public outrage (Davies 2019). This agreement proved short-lived, collapsing in January 2022 when Hamdok resigned, effectively dissolving both the government and the previous agreement (Davies 2019). Since then, Sudan has lacked civilian leadership, with military commander General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan becoming the de facto head of state (Al Jazeera 2023).

In December 2022, a framework agreement was signed between the military and a coalition of some pro-democracy forces, facilitated by the United Nations (UN), the African Union (AU) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). The agreement promised a two-year transition to democratic elections, during which the military pledged to transfer power to civilian authorities (Gavin 2023).

However, delays in reaching consensus and ongoing disputes over the future governance structure, especially of the security sector, led to the outbreak of violent clashes between the SAF and RSF in April 2023 (Ricket 2023; Willis 2025; Center for Preventive Action 2025). In 2025, the SAF regained control of Khartoum from the RSF (Willis 2025). Despite this shift in the balance of power, violence has not diminished. On the contrary, civilian actors and pro-democracy groups have faced a backlash from both warring parties due to their vested interest in suppressing the democratic movement in the country (Khalafallah 2025).

Military and paramilitary actors exert strong control over Sudan’s most lucrative economic sectors, operating without institutional oversight. Dispersed networks of firms linked to these forces span multiple industries, including gold mining, which has become the ‘new oil’ for Sudan, following large discoveries in 2011 (The Enough Project 2017).

The current conflict has resulted in approximately 150,000 deaths and the displacement of nearly 14 million people, triggering a severe humanitarian crisis (Freedom House 2025a). According to NGOs and the UN, Sudan is currently facing the world’s largest humanitarian crisis, with hundreds of thousands at risk of famine and widespread violations of international humanitarian law being documented (Savage 2025).

The civil war has further exacerbated Sudan’s already high levels of corruption, creating new opportunities for resource extraction by armed actors at the expense of the general population. These include the obstruction and diversion of humanitarian aid, engagement in smuggling and negotiations of illicit deals with importers, such as fee exemptions in exchange for in-kind payments (Paravicini and Michael 2024; STPT and New Features Multimedia 2025).

Extent of corruption

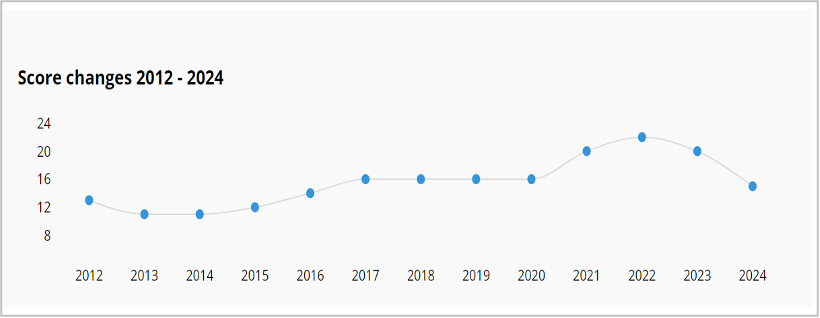

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) for 2024, Sudan scored 15 out of 100, ranking it 170 out of 180 countries (Transparency International 2025). Its score is below the regional average for sub-Saharan Africa of 33, and it declined 7 points between 2022 and 2024 (Transparency International 2025; Banoba et al. 2025).

Figure 2: CPI score for Sudan (2012-2024).

Source: Transparency International 2025.

While Sudan’s score improved following the ousting of al-Bashir, it started to decline again after the coup jointly orchestrated by the SAF and RSF to dissolve the transitional government. The subsequent failure to reach an agreement on Sudan’s future governance structure ultimately led to civil war (Freedom House 2025b; Willis 2025; Center for Preventive Action 2025).

Freedom House’s (2025b) Freedom in the World report categorises Sudan as ‘not free’. The country’s score has sharply declined from 17 in 2020 to just 2 in 2024 (Freedom House 2025b). In its latest report, Freedom House (2025) highlights the absence of effective anti-corruption laws and institutions in Sudan. It notes that bodies established by the transitional authorities to investigate financial crimes committed under al-Bashir’s regime, such as the Empowerment Removal Committee,4661bfaa8735 were suspended following the October 2021 coup (see also Sudan Tribune 2025b).

Similarly, the latest Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) (2024) report notes that corrupt practices from the al-Bashir’s era, including abuse of power and the misappropriation of public funds, continue without accountability. Efforts to establish anti-corruption institutions after al-Bashir’s removal were largely unsuccessful, and those that were created were quickly dismantled and their members subjected to politically motivated persecution (BTI 2024).

The World Bank’s (2024) Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI)ab3c6fc88d7f for 2023 assign Sudan a control of corruption9d8991d24d79 score of -1.50, indicating a decline compared to 2018, the year before al-Bashir was ousted. This aligns with other assessments suggesting that corrupt practices persisted and continued after the 2019 coup (e.g. BTI 2024). The rule of lawe8128d5bb181 score also worsened, dropping from -1.14 in 2018 to -1.67 in 2023, placing Sudan near the bottom globally, in the 4.25 percentile rank (World Bank 2024).

Table 1. Sudan’s scores on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) in 2013, 2018, and 2023.

|

|

2013 |

2018 |

2023 |

|||

|

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

|

|

Voice and accountability |

-1.78 |

3.76 |

-1.85 |

2.91 |

-1.60 |

5.88 |

|

Political stability |

-2.19 |

2.37 |

-1.82 |

6.13 |

-2.47 |

1.90 |

|

Government effectiveness |

-1.49 |

4.27 |

-1.63 |

4.76 |

-1.98 |

2.36 |

|

Regulatory quality |

-1.46 |

6.64 |

-1.64 |

4.29 |

-1.60 |

4.72 |

|

Rule of law |

-1.28 |

7.98 |

-1.14 |

10.95 |

-1.67 |

4.25 |

|

Control of corruption |

-1.49 |

0.47 |

-1.46 |

6.19 |

-1.50 |

4.25 |

Source: World Bank 2024.

The latest round of the Afrobarometer (2024) survey, conducted in late 2022 in Sudan, indicates that the most important problem facing the country is the management of the economy, with 43.3% of respondents identifying it as their primary concern. Corruption as an issue ranked fifth, following the economy, education, crime and security, and health, with 4.7% of respondents citing it as the most pressing issue (Afrobarometer 2024: 11). When asked how often officials in Sudan who commit crimes go unpunished, 73.1% of respondents answered ‘often’ or ‘always’, suggesting widespread impunity for public officials (Afrobarometer 2024: 37).

This survey also revealed rising perceptions of corruption. A total of 66.2% of respondents stated that corruption had ‘increased a lot’ over the past year. When including those who said it had ‘somewhat increased’, the figure rises to 79.7% (Afrobarometer 2024: 47). Regarding government performance in countering corruption in the government, 90.8% of respondents rated it as ‘fairly badly’ or ‘very badly’ (Afrobarometer 2024: 58). Additionally, 62.2% of respondents stated that ordinary citizens risk retaliation or other negative consequences if they report corruption (Afrobarometer 2024: 47).

Transparency International’s Governance Defence Integrity Index (GDI) for 2020 found Sudan’s security sector to be at critical risk of corruption, assigning it the lowest-possible rank. The report highlighted that civilian democratic control and external oversight are non-existent in the defence sector, corruption is widespread and there are no anti-corruption mechanisms in place (GDI 2020).

Forms of corruption

State capture

Omar al-Bashir’s regime was characterised by the systematic diversion of public resources to regime cronies, family members and armed actors, as well as the enactment of tailor-made laws that benefited narrow interests at the expense of the broader public. This was facilitated through an elaborate network of politically controlled firms (Dabanga 2017; Baldo 2018; The Enough Project 2017; De Waal 2019).

Regime-connected businesses received preferential treatment, enabling them to extract public resources. The Sudanese economist Siddig Ombadda estimated that the NCP owned over 500 firms spanning various sectors, including oil and gold, land deals and the arms industry (The Enough Project 2017: 15).

During al-Bashir’s rule, the government engaged in legislative capture to facilitate extraction from the most lucrative sectors. For example, constitutional amendments during al-Bashir’s rule further centralised control over land allocation, granting the president authority to allocate land for investment, which was previously the responsibility of individual states. In 2015, the then-minister of investment announced the establishment of a special body empowered to allocate land, order the removal of local populations and determine compensation without any legal mechanism for appeal. This move further consolidated regime control over land distribution while evading accountability (The Enough Project 2017: 31). As a result, al-Bashir’s cronies and NCP insiders were able to exploit land to accumulate wealth and sustain patronage networks (The Enough Project 2017: 31).

Moreover, politically connected businesses were granted access to the official, overvalued exchange rate intended for the import of strategic goods. As highlighted in a report on the Sudanese economic crisis, the preferential allocation of hard currency to government-owned firms and parastatals created opportunities for corrupt practices in public procurement, including false invoicing for allegedly procured strategic goods and the payment of kickbacks to foreign suppliers or officials responsible for awarding contracts (Baldo 2018: 9). One example refers to the 2016-2017 period when a group of businessmen and senior bank officials, including individuals at Bank al-Shamal al-Islami, allegedly conspired to embezzle US$230 million earmarked for the import of life-saving drugs at subsidised prices. The scheme involved traders and bank officials selling dollars acquired at official rates on the black market to generate illicit profit (Baldo 2018: 9).

A 2017 report on corruption in Sudan’s telecommunication sector highlighted that companies shield themselves by appointing influential individuals from the president’s inner circle to their boards (Dabanga 2017). The report noted the existence of entrenched corruption networks engaged in the manipulation of public funds, violations of citizens’ freedoms and surveillance of the population (Dabanga 2017).

Corruption involving high-level officials persisted after the coup that overthrew al-Bashir. For example, in 2021, a scandal emerged involving the minister of finance, who granted customs exemptions for his nephew’s car (BTI 2024).

Both before and after the 2019 coup, military and paramilitary actors continued to dominate Sudan’s most lucrative sectors, particularly gold mining, operating with little or no scrutiny (The Enough Project 2017; Abdelaziz et al. 2019; Windridge 2021). In 2019, leaked documents revealed that the RSF controls a large share of Sudanese gold market through a network of front companies based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Sudan (Global Witness 2019). During al-Bashir’s regime, the SAF and RSF were allowed to engage in unofficial gold exports through their front companies. In the case of SAF, these were nominally state-owned, and in the case of RSF, they were privately owned by their commanders (Soliman and Baldo 2025).

According to a recent report by the Sudan Democracy First Group (2024a), approximately 250 companies are linked to the SAF, RSF and other security services. These companies operate across various sectors, including in the production and export of gold and other minerals, marble, leather, livestock and control over 60% of the wheat market (Sudan Democracy First Group 2024a). Their activities also extend into communication, aviation, construction, real estate development and transportation. These firms are not subject to audit and operate outside the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance yet receive substantial government privileges such as tax exemptions (Sudan Democracy First Group 2024a).

The auditor general’s 2020 report noted that ten companies, among which were SAF-linked firms, received tax exemptions ranging from 10 to 26 years, and highlighted that such long exemptions have no basis in any Sudanese law (Sudan Democracy First Group 2024a).

Notable companies affiliated with the SAF include Defence Industrial Systems (DIS), which oversees a number of civilian companies with opaque ownership structures, and Zadna International Company for Investment, which engages in a wide range of investment activities (Sudan Democracy First Group 2024a). Companies affiliated with the RSF include Al Junaid Multi Activities Co Ltd, founded by RSF leader Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti), and involving members of his family. Al Junaid is active in gold mining and exportation. Another RSF-linked entity is GSK Advance Company Ltd, led by Hemedti’s younger brother, which operates in the field of information systems and surveillance technologies (Sudan Democracy First Group 2024a: 5). Some of these companies were added to the US Department of the Treasury (2023) sanctions list in June 2023 for generating revenue from and contributing to the conflict in Sudan.

New forms of resource extraction have emerged during the ongoing civil war, with the capture of institutions reportedly reaching unprecedented levels (STPT and New Features Multimedia 2025). Both the SAF and RSF are involved in smuggling goods, such as food, fuel, medicine and Starlink internet devices (Amin 2024). These groups also extort bribes from civilians and impose levies on roadside checkpoints (Amin 2024). These smuggling networks are reportedly either directly run by the SAF or RSF, or are under their protection (Amin 2024). For instance, the RSF reportedly engages in the fuel trade with loyal businesses, charging hefty fees to allow trucks to pass through RSF controlled areas in Darfur (STPT and New Features Multimedia 2025: 12).

There is also evidence that the SAF exempts importers from storage and port charges in exchange for 70% of these fees and charges in-kind, particularly involving the importation of flour, sugar and other food products, all carried out without any official documentation (STPT and New Features Multimedia 2025).

Political interference reportedly shields connected businesses from the reach of state institutions. For instance, after the bank accounts of a petroleum importer were frozen due to unpaid tax arrears (amounting to US$40 million), the secretary general of the tax authority, Mohamed Ali Mustafa, was dismissed (STPT and New Features Multimedia 2025: 10).

Petty corruption

The latest available survey evidence suggests that perceived bribery levels in Sudan remain relatively high. According to the Global Corruption Barometer survey conducted prior to the coup against al-Bashir, between March and August 2018, approximately one in four citizens (24%) reported paying bribes595a9deac55c (Transparency International 2019). This was the third highest bribery rate among the surveyed countries,20b54e95924f following Lebanon and Morocco (Transparency International 2019). Specifically, 33% of respondents in Sudan reported bribery involving the police, placing it just behind Lebanon in terms of police-related bribery (Transparency International 2019: 18).

The most recent Afrobarometer (2024) survey conducted in Sudan in late 2022 highlights high levels of perceived corruption among civil servants and police. According to the findings, 45.4% of respondents believed that ‘most’ or ‘all’ civil servants were involved in corruption, while 64.1% expressed the same view regarding the police (Afrobarometer 2024). In the case of the police, corruption predominantly takes the form of petty bribery. An earlier Afrobarometer (2022) survey, conducted in 2021, found that substantial proportions of those who interacted with public services reported having to pay bribes to obtain the services they needed. The highest rates were recorded in interactions with the police: 51% of respondents reported paying bribes to avoid problems with the police, while 42% reported paying bribes to receive police assistance (Afrobarometer 2022: 3).

Evidence from the period before the 2019 coup suggests that corruption was widespread among traffic police as well as in the healthcare sector. For instance, on-the-spot fines for traffic violations were originally introduced to ease the burden on the courts by allowing drivers to settle minor offences without legal proceedings. However, this mechanism was widely abused and became a revenue source for the traffic police and for personal benefits (Dabanga 2016a). Following the introduction of an internal regulation that allocated 10% of revenue generated by traffic police officers as incentives for the traffic police department, the traffic police units reportedly increased the number of checkpoints on major roads to boost revenue, effectively institutionalising rent-seeking behaviour (Dabanga 2016a).

In the healthcare sector, evidence from before 2019 indicates corrupt practices, including bribery of medical staff in public hospitals to expedite placement on surgery waiting lists (Dabanga 2016b).

Focus areas

Agriculture

Prior to the outbreak of the civil war in April 2023, Sudan’s agriculture sector was the backbone of the national economy (Hoffmann et al. 2024). For example, Sudan was a leading exporter of various cash crops, including groundnuts, sunflower, soybean and sesame (ITA 2022; Hoffmann et al. 2024). Owing to its vast arable land, Sudan was often referred to as ‘the breadbasket of the region’ (Hoffmann et al. 2024: 9). However, for a range of structural and political reasons (e.g. a lack of key inputs, such as fertilisers), the sector consistently underperformed, failing to reach its full potential even before the current war. This underperformance contributed to low agricultural productivity and recurring hunger crises (Hoffmann et al. 2024: 9).

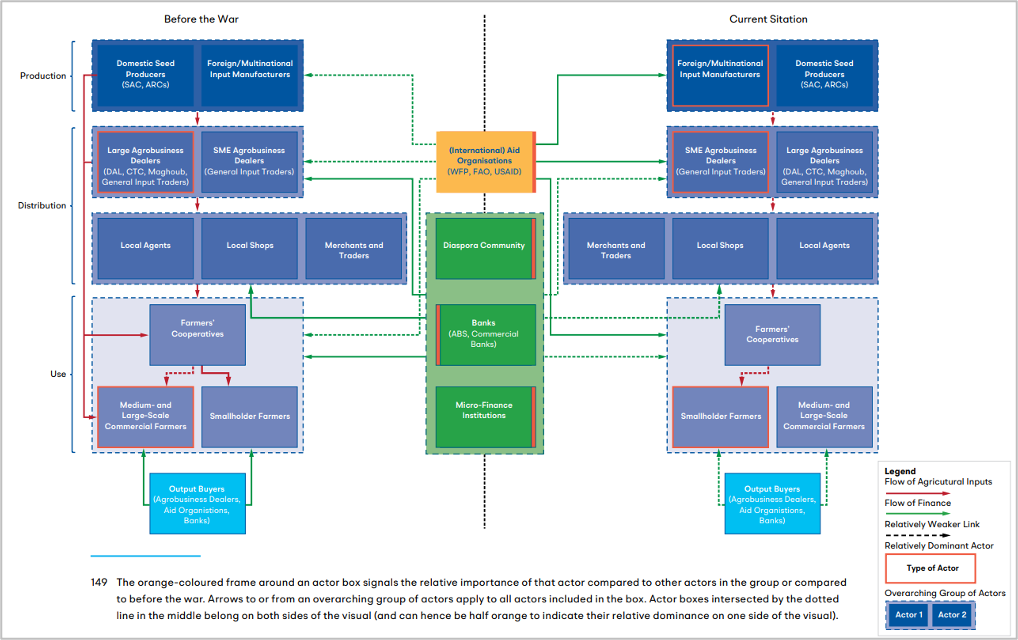

Figure 3: Sudan’s agricultural input supply before the war and now.

Source: Hoffmann et al. 2024: 46.

The current war has had a devastating impact on agricultural production in Sudan. One major factor is that most agricultural input providers, which were mainly based in Khartoum, ceased operations or relocated to the eastern regions of the country, further restricting already limited access to essential inputs (Hoffmann et al. 2024: 10). In addition, the land available for crop cultivation has been significantly reduced due to the conflict (Hoffmann et al. 2024: 10).

Studies have identified numerous corruption risks in the agriculture sector, both before and after the coup that ousted al-Bashir. These include the use of tailor-made laws to facilitate land grabbing,395b281c54aa secrecy in land deals with foreign investors, the strong influence of military and paramilitary actors over the sector and the diversion of agricultural funds, among other issues.

During al-Bashir’s rule, some adopted legislation has facilitated land grabbing. A report by the Sudan Democracy First Group (Taha 2016) highlighted that the imposition of formal laws (the Unregistered Land Act of 1970 and the Civil Transaction Act of 1984) on the use of unregistered lands facilitated land tenure insecurity (Taha 2016: 2). A combination of factors, including the strength of customary laws, limited public awareness of statutory laws, and practical barriers to land registration meant that many Sudanese failed to register their land.

As a result, the state was able to claim ownership of approximately 90% of land, which was then made available for transfer to private, often politically connected individuals (Taha 2016). This system enabled the government to use land allocation as a tool for political patronage (The Enough Project 2017: 30; Taha 2016). Despite provisions in the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which called for laws incorporating customary land rights, the government continued to grant long-term leases over community land, typically to well-connected commercial interests (e.g. private investors, military personnel), without consulting local populations (Taha 2016: 2).

The same report further notes that these land deals lack transparency, particularly in relation to large-scale investment projects, agricultural corridors development and associated supply chains. This opacity increases risks of elite capture in international land deals, including the use of development projects for kickbacks and land as a means of political patronage (Taha 2016: 2). The UAE has been especially active in investing in Sudan for its own food security needs, including in agricultural expansion projects and the development of a Red Sea port (GRAIN 2025).

As El Obeid (2024) notes, most deals made by former president al-Bashir with Gulf countries were highly secretive. For instance, in 2016, he signed a special law granting Saudi Arabia 1 million acres of farmland for 99 years in exchange for financial support in the Upper Atbara and Setit Dams Project (El Obeid 2024: 27). This law explicitly prohibits either party from disclosing any information about the deal to third parties (El Obeid 2024: 28) While the secretive nature of these deals does not necessarily imply corruption, such deals significantly increase corruption risks.

Military and paramilitary actors have exerted strong influences over agriculture and other sectors both before and after al-Bashir’s ousting. A recent report identifies four key strategies used by the SAF and RSF across various agri-food value chains in Sudan (Resnick et al. 2025):

- exclusive capture and rent extraction

- competition through biased licensing and quota allocations

- silent acceptance of private competitors when value-addition is overly complex

- innovation when potential is high and private sector presence is lacking

The capture strategy is particularly evident in the livestock production and trade, a critical industry upon which at least 26 million Sudanese depend for their livelihoods (Resnick et al. 2025). Capture is possible, according to Resnick et al. (2025), due to the absence of private sector actors, relatively low technical complexity and longstanding networks via Egypt and Gulf states, maintained by the SAF and RSF. The livestock value chain in Sudan is fragmented, involving input suppliers, pastoralists, herders, brokers and others, offering numerous entry points for rent-seeking (Resnick et al. 2025: 14). Both the SAF and RSF are active in the livestock trade. For instance, a company affiliated with SAF, Multiple Directions Company (MDC), opened an industrial slaughterhouse in 2020. This facility, previously state-owned, was transferred to SAF control via a bilateral agreement in 2021, allowing it to export cattle to Egypt (Resnick et al. 2025: 14). The SAF profits from this trade while incurring minimal operational costs, as the Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning (MoFEP) finances transport, fuel and drivers (Resnick et al. 2025: 15).

Where private actors are active, military and paramilitary actors engage in distorted competition, benefiting from advantages such as preferential licensing and quota allocations (Resnick et al. 2025). In the wheat milling industry, for example, SAF-affiliated companies enjoy exemptions from numerous levies and taxes, giving them a significant edge over private competitors (Resnick et al. 2025: 16). A notable case is that of the company Seen, which was controlled by the National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS) until the 2019 coup, after which it came under SAF ownership. The company aimed to take over the wheat flour business, especially in circumstances of increased import to satisfy domestic demand (Resnick et al. 2025: 17). The company benefited from numerous advantages over its competitors, such as preferential access to wheat subsidies (Resnick et al. 2025: 17).

Resnick et al. (2025) point out that, in capital-intensive sectors requiring technical expertise and facing established private competition, military and paramilitary actors tend to focus on exports to expand foreign exchange reserves. Although they have entered markets such as gum arabic and cotton, they have largely failed to dominate due to the complexity and competitiveness of these sectors. The SAF entered both markets through its companies, but their involvement appears primarily driven by the goal of accumulating foreign currency (Resnick et al. 2025: 20).

Finally, Resnick et al. (2025) indicate that in sectors with high potential and limited private sector presence, military actors may even pursue innovation. This is evident in horticulture, where Zedna, a company which has board members from both SAF and RSF, has made significant investments (Resnick et al. 2025: 21). One of Zadna’s projects spans 1 million acres, which were reportedly acquired using opaque means (Resnick et al. 2025: 21).

Amid the ongoing civil war and rapidly deteriorating famine conditions (Mishra 2024), military and paramilitary actors have also been implicated in food aid diversion. For instance, in 2024, the UN World Food Programme launched an investigation into two of its senior officials in Sudan over allegations of fraud and concealing information from donors about its ability to deliver food aid to civilians, as these officials allegedly hid the role of the Sudanese army in obstructing aid (Paravicini and Michael 2024). Meanwhile, the RSF has imposed various restrictions on humanitarian operations in the areas under its control. These include demands for higher fees and tighter oversight of aid operations, including in recruitment and security processes. Almost half of the Sudanese population is reportedly suffering from acute hunger, with the most severe conditions found in RSF controlled areas (Sakr 2025).

Energy

Sudan possesses a diverse mix of energy sources, both renewable and non-renewable. The country’s energy supply is primarily derived from crude oil, hydroelectricity and biomass, with a significantly smaller share coming from other renewable sources (Al-Rikabi et al. 2025). In terms of electricity generation, hydropower is the dominant source, accounting for approximately 54.6% of total production, followed by fossil fuels (44.62%), while renewable sources contribute only 0.78% (Al-Rikabi et al. 2025: 4).

Despite its resource potential, Sudan’s energy sector is plagued by inadequate infrastructure, mismanagement, and an uneven distribution of power grids, with only 21% of the generated electricity reaching rural regions (Al-Rikabi et al. 2025). These challenges have resulted in frequent electricity outages, inconsistent supply and rising energy costs for industrial consumers (Al-Rikabi et al. 2025). Millions of Sudanese experience hours-long power cuts, with only 47% of the population having access to electricity (Basheir 2022; Al-Rikabi et al. 2025). According to 2018 estimates, just 32% of the population had access to electricity through the national grid, primarily concentrated in urban areas, while five federal states of Darfur and the region of South Kordofan were excluded (Basheir 2022). Many residents in remote areas are forced to rely on traditional energy sources, such as biomass, kerosene and charcoal (Al-Rikabi 2025: 4).

The situation worsened following the secession of South Sudan in 2011, which led to Sudan losing 75% of its oil production, 60% of its biomass energy resources and 25% of its hydropower capacity (Al-Rikabi et al. 2025: 3).

However, Sudan has substantial untapped renewable energy potential. Although most of the country’s renewable energy currently comes from hydropower, Sudan also has abundant solar resources, generates significant agricultural biomass annually and possesses potential for wind and geothermal energy development (Al-Rikabi et al. 2025: 5).

Large-scale energy projects in Sudan have historically been associated with corruption, primarily due to the reliance on government-connected companies that drastically inflated project costs. A prominent example is the Merowe Dam project, a major development project officially aimed at expanding the electricity supply network, but a lack of oversight, corruption and nepotism in selecting companies to construct it resulted in exorbitant debt of US$3 billion, while the lack of transparency in the project resulted in increasing environmental costs (Basheir 2022). Major contracts for the project were given to three European firms, Germany’s Lahmeyer International, France’s Alstom and Switzerland’s ABB, all of which have been involved in controversial hydropower projects in the past (Hildyard 2008: 3). In 2004, Lahmeyer International was even convicted in the Lesotho high court for bribing the former chief executive of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project in exchange for favourable contract decisions (Probe International 2003).

Fuel subsidies during al-Bashir’s regime also became a significant avenue for corruption. Under this policy, fuel importers were allowed to purchase US dollars at a preferential exchange rate. They could then overstate fuel imports and sell the subsidised dollars on the black market for profit (ICG 2020).

In the current context of civil war, petroleum imports remain a major source of corruption, reflecting the undue influence of politically connected businesses on state institutions (STPT and New Features Multimedia 2025). Specifically, following the outbreak of the civil war, some businessmen who had enriched themselves under al-Bashir reportedly demonstrated loyalty to the SAF by providing donations and food. In return, they were granted a monopoly position in gold export and the import of fuel, sugar and other essential goods. These actors also benefited from leniency in tax and other obligations, such as storage fees (STPT and New Features Multimedia 2025: 5). These kleptocratic practices not only entrench corruption but also prolong the ongoing devastating war.

Meanwhile, the RSF has also been active in the fuel trade in areas that it controls, collecting transit fees to fuel tankers and trucks (STPT and New Features Multimedia 2025).

Environment

Sudan faces a range of pressing environmental challenges, including deforestation, land degradation, biodiversity loss, air pollution, food insecurity and others (UNEP 2020).

Following major gold discoveries in 2011, which coincided with South Sudan’s independence and Sudan’s subsequent loss of 75% of its oil reserves, gold became the country’s ‘new oil’ (The Enough Project 2017: 24). While official gold production and revenues have steadily increased over the years, they were significantly affected by the outbreak of the civil war (Soliman and Baldo 2025). Control over the gold sector is now shaping the outcome of the civil war, with the billion-dollar gold trade providing the most significant source of income for the two main conflict parties and feeds an associated cross-border network of actors including other armed groups, producers, traders, smugglers and external governments (Soliman and Baldo 2025:5).

Poor oversight of the gold mining sector has also contributed to serious environmental degradation and health risks, primarily due to the use of toxic and polluting materials (Ayin Network 2019; Ziada et al. 2023; Soliman and Baldo 2025). For example, gold mining in the Delgo settlement in Northern State, conducted by Delgo Mining (a joint venture between the Sudanese government and the Turkish company Tahe Mining), has faced strong opposition from local residents due to alleged environmental contamination (Soliman and Baldo 2025: 19). Despite multiple court rulings ordering the company to stop operations, this has not happened due to close business ties with still influential members of the former al-Bashir regime (Soliman and Baldo 2025: 19).

Although environmental impact assessments (EIAs) are legally required, enforcement is weak. As a result, environmental harm, especially in the context of artisanal mining, continues to escalate (Mitchell 2025). For example, proper EIAs were never carried out for the Merowe Dam project (Ejatlas 2022). Specifically, in 2005, the NGO International Rivers received a confidential EIA report produced by Lahmeyer International and passed it on to theSwiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology for review (Ejatlas 2022). The review showed that the report did not follow World Bank or World Commission on dams guidelines on how to write EIA reports for dam projects (Ejatlas 2022).

Another major environmental concern is illegal logging (used for selling as wood or charcoal) profiting militias, which causes further deforestation (ADF 2022). Such practices reportedly intensified after the fall of the al-Bashir regime as militias affiliated with the military, seeking financial support from political patrons, turned to forest exploitation in rural areas to generate income (ADF 2022).

Obstacles to sustainability initiatives

Recent literature identifies several factors, which are exacerbated by corruption, that may hinder efforts toward a renewable energy transition in the future post-conflict period in Sudan. Given that the ongoing conflict has caused severe disruptions to energy infrastructure, Ali et al. (2024) suggest that the post-conflict context presents an opportunity to invest in a modern, sustainable energy infrastructure.

One of the primary structural barriers to renewable energy transition is financial due to the investment costs needed. This has been further exacerbated with the current civil war, which increased costs of solar photovoltaic energy due to disruptions in supply chains and increased demand due to widespread damage to electricity networks (Ali et al 2024). As such, the financial, technological and storage-related challenges associated with renewable energy require robust state support to enable an effective transition (Ali et al 2024). However, this dependence on state resources also creates corruption risks, as evidence from other countries in the region suggests. For example, evidence from Kenya suggest that political officeholders have reportedly used their political positions to allocate resources for solar projects in a biased manner, diverting public spending to politically connected actors (Sovacool 2021).

Ali et al. (2024) also highlight the lack of clear policies and regulatory frameworks governing energy transition in Sudan. This absence of coherent planning has significantly hindered progress, and the limited advancements made under the civilian government have largely been reversed by the ongoing civil war.

In addition to general structural challenges, there are specific barriers associated with certain types of renewable energy. For example, Al-Rikabi et al. (2025: 18) identify several barriers to the development of wind farms in Sudan, including:

- infrastructure deficiencies, such as the need to construct new roads to transport equipment to wind farm sites

- market risks, stemming from Sudan’s low levels of economic development and the capital-intensive nature of wind projects with extended payback periods

- country-related risks, including extremely high levels of corruption

- low political stability, which deters long-term investments

Legal and institutional framework

International conventions and initiatives

During al-Bashir’s regime, Sudan ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) and the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption, although little of it has been translated to the national legislation (Schütte 2020).

Sudan is also a member of the Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force (MENAFATF). It was identified as having strategic deficiencies in 2010 and exited the FATF’s enhanced monitoring list in 2015 (IMF n.d.). Its financial information unit (FIU) is also part of the Egmont Group (Egmont Group n.d.).

Domestic legal framework

There are several key pieces of legislation which contain anti-corruption provisions in Sudan. The 2019 constitutional declaration stipulated the establishment of commissions tasked with uncovering the extent of corruption under the previous regime and reclaiming assets that had escaped state scrutiny (Davies 2019). It also required that, upon assuming office, the chair and members of the sovereignty council and cabinet, as well as governors or ministers of provinces or states and members of the transitional legislative council, submit asset declarations for themselves and their immediate family members (spouses and children) (Constitute project 2021).

Furthermore, the declaration prohibited these officials from engaging in private professions or participating in commercial or financial activities while in office (Constitute project 2021). In practice, however, none of the military leaders in the sovereignty council fully disclosed their assets (Davies 2019: 29). Amendments to the constitutional declaration in February 2025 extended the transitional period by 39 months and significantly strengthened the power of the military by increasing its presence in the sovereignty council and expanding the authority of the council over key appointments (including within the judiciary), policy decisions and legislation (Sudan Tribune 2025a).

The penal code of 2003 criminalises both active and passive bribery, and corruption related offences, including attempted corruption, bribery of foreign officers and money laundering (Martini 2012; Sunjka 2021). Additionally, the anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing law criminalises money laundering and the financing of terrorist organisations (Arab Legislation Portal n.d.).

The Public Procurement, Contracting and Disposal of Public Assets Act (2010) punishes corruption practices by issuing bans to suppliers and bidders in future tenders for up to ten years, with a possible loss of current contracts and criminal sanctions, including imprisonment (Ardigo 2020).

The Political Parties Act (2007) and Electoral Act (2008) stipulate that political parties and candidates must regularly report on their finances and electoral campaign finances (International IDEA 2018). While, in theory, this information is to be made publicly available, that is not the case in practice (Ardigo 2020). And, finally, the law of November 2019 on banning the National Congress Party and confiscating its assets (Dabanga 2019; France24 2019).

There are poor safeguards for whistleblowers in Sudan. The Law on the National Commission for Transparency, Integrity and Combating Corruption, which was passed in 2016 guaranteed privacy rights of whistleblowers, stipulating monetary and prison sentences for those who reveal their personal data (Suliman 2019b). However, this law was repealed in 2021, with the adoption of the Anti-Corruption and Public Funds Recovery Commission Law.7abf79bdbd86 Following the ousting of al-Bashir and the formation of the transitional civilian-military government, the attorney general issued a circular on the protection of whistleblowers, victims, witnesses and experts, calling all prosecutors to protect whistleblowers in investigations related to dangerous criminal cases or those implicating influential officials and to ensure that their identities are protected (Al Taghyeer 2021).

Institutional framework

Following the 2021 coup, anti-corruption efforts in Sudan were significantly curtailed, and much of the progress made by previous anti-corruption bodies was reversed (Dabanga 2024). Government agencies remain highly politicised, with little to no accountability for rule violations committed by their members (BTI 2024).

Empower Removal Committee (ERC)

The ERC was established in 2019 to recover assets believed to have been acquired through illegal means by leaders linked to the al-Bashir regime (Dabanga 2021).

The committee achieved some notable successes in its work. It reportedly investigated financial misconduct involving hundreds of state employees, including ambassadors, civil servants and legal advisers, and exposed a vast network of military linked companies embedded in various sectors of Sudan’s economy (Davies 2019). For instance, in May 2020, the ERC revealed that the SAF related company, Defence Industrial System, owned more than 200 companies with combined annual revenues of US$2 billion (Davies 2019: 28).

The ERC also confiscated hundreds of assets held by key figures from the al-Bashir era. In 2020, it was announced that the committee had seized 79 real estate properties illegally acquired by members of the Islamic movement during al-Bashir’s rule, estimated to be worth US$1.20 billion (Dabanga 2020).

Despite these efforts, the overall impact of the ERC was limited, primarily due to the weak influence of civilian authorities within the transitional governance structure (Davies 2019).

Following the 2021 coup, the committee was dismantled. In October 2024, Sudan’s chief justice established a new body to review the ERC’s decisions (Dabanga 2024). In the aftermath of the coup, many ERC decisions were nullified and three of its members were detained in February 2022 (Dabanga 2024). In January 2025, the public prosecutor for economic crimes designated 24 former ERC members as fugitives, alleging their involvement in breaches of the penal code, including corruption related offences (Sudan Tribune 2025b).

Auditor general

The 2019 constitutional declaration reaffirmed the position of the auditor general as an independent institution (Constitute project 2021).

However, the effectiveness of this body has been limited due to political interference and a lack of resources (Ardigo 2020; Elbushari 2017). Moreover, military and security investment companies, which are involved in a number of lucrative sectors through a vast network of companies, are not subject to audit, further undermining transparency and accountability in public financial management (Sudan Democracy First Group 2024a).

Anti-corruption commission

In January 2011, President al-Bashir ordered the establishment of an anti-corruption taskforce, tasked with monitoring corruption related reports in the media and coordinating with the presidency and other relevant authorities to complete information on issues raised in relation to corruption at the state level (Sudan Tribune 2011).

It was not until 2016 that the Law on the National Commission for Transparency, Integrity and Combating Corruption was adopted, formally establishing the anti-corruption commission. The commission was mandated to develop policies to enhance transparency and integrity, counter corruption, receive grievances and reports related to corruption and take necessary measures, collect data, statistics and information on corruption, and crate a database, among other tasks (FAOLEX Database 2023).

The 2019 constitutional declaration stipulated the establishment of several commissions, including the anti-corruption and public funds recovery commission (Constitute project 2021). The 2016 law was later repealed and replaced with the Anti-Corruption and Public Funds Recovery Commission Law of 2021 (FAOLEX database 2023; Rahman 2021).

Anti-Corruption Investigation Unit (ACIU)

The ACIU was established during al-Bashir’s regime in August 2018, operating under the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) authority, with a mandate to counter corruption in government and preserve public money (US Department of State 2018).

At its inauguration, it was announced that the body would include staff from the office of the state comptroller, the central bank, the judiciary, the attorney general, the tax bureau and the customs authority, working in collaboration with NISS officers (MEMO 2018).

Public prosecutor’s office

The 2019 constitutional declaration defines the public prosecutor as an independent authority. The supreme council of public prosecution is responsible for nominating the prosecutor-general and their assistants, who are then appointed by the sovereignty council (Constitute project 2021).

After the fall al-Bashir, efforts were made to address the politicised judiciary of his era. As part of these efforts, in 2021, the ERC removed over 20 public prosecutors from office (Freedom House 2025b). However, the committee faced a backlash early on. In 2021, the appeals department of Sudan’s high court in Khartoum nullified the decisions of the ERC with regards to the removal of judges, prosecutors and other judicial employees (Dabanga 2024).

In the aftermath of the 2021 coup, General al-Burhan replaced the public prosecutor and chief justice with former officials from the NCP (Freedom House 2025b).

Other stakeholders

Media

As noted by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) (2024), the 2021 coup marked the return of media censorship and information control in Sudan. Moreover, following the outbreak of civil war in April 2023, threats and attacks against journalists have intensified (RSF 2024; Freedom House 2025b).

The media landscape remains largely state controlled, including Sudan National Radio Corporation and Sudan National Broadcasting Corporation (RSF 2024).

Since the outbreak of the civil war, both the SAF and RSF have reportedly used internet shutdowns to as a tool to control the flow of information, isolating millions, similar to tactics employed during the al-Bashir era (Mnejja 2024). These shutdowns are strategically implemented to disrupt communication and control media narratives (Mnejja 2024).

Civil society

In the immediate aftermath of al-Bashir’s ousting in 2019, some restrictions previously imposed on civil society organisations were relaxed. However, conditions for civil society deteriorated again following the outbreak of the civil war in April 2023 (Freedom House 2025b). Obstacles were introduced for NGOs attempting to renew their registrations (Freedom House 2025b). NGOs and aid workers have been subjected to violent attacks and at least three World Food Programme employees were killed in Darfur shortly after the conflict erupted in 2023 (Freedom House 2025b).

Key civil society initiatives and organisations for anti-corruption include:

- Anti-corruption Taskforce Sudan, a newly established coalition of local Sudanese civil society organisations, committed to identifying and curbing corruption in Sudan (Sudan Democracy First Group 2024b)

- Sudan Transparency and Policy Tracker, established in 2022 to respond to the needs for a more organised anti-corruption campaigning; they publish in-depth studies identifying corruption risks in various sectors of the economy

- Sudan Democracy First Group, committed to promoting inclusive democracy through three programme areas: security sector reforms, transitional justice and Sudan transparency initiative

- The Sudanese Consumers Protection Society, which handles consumer complaints and is a leading voice in education the community on consumer protection issues in Sudan

Resistance committees also have an extensive history of organising since 2010, engaging in organising protests, supporting victims of abuse and injustice, coordinating advocacy and resistance efforts with local governments (Abbashar 2023). Following the outbreak of the conflict in 2023, they stepped in to provide social protection and humanitarian relief provisions for citizens affected by the war (Abbashar 2023).

- This is the most powerful paramilitary group which emerged from al-Bashir’s period of rule. Its leader, Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti), rose to become one of Sudan’s wealthiest people by seizing control of large shares of the gold mining sector (Center for Preventive Action 2025).

- The legislative council, under the political agreement, would be composed of 67% FFC members and 33% individuals who did not sign the FFC’s declaration of freedom and change (Davies 2019: 11).

- The council of ministers was to consist of a prime minister chosen by FFC and a cabinet of no more than 20 members (Davies 2019: 11).

- It was to consist of eleven members, of which five were chosen by the FFC, five by TMC and one jointly by the two parties (Davies 2019: 11).

- The legislative council is not currently operational.

- Full name: Committee for Dismantling the June 30, 1989 Regime, Removal of Empowerment and Corruption, and Recovering Public Funds (BTI 2024).

- This indicator captures the perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in the rules of society and specifically the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence (World Bank no date b).

- This indicator measures the strength of public governance based on perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain (including both petty and grand corruption), as well as the capture of the state by elites and private interests (World Bank no date a).

- Scores range from -2.5 to 2.5 (higher scores correspond to a better governance) (World Bank 2024).

- The surveyed countries included: Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Palestine, Sudan and Tunisia (Transparency International 2019).

- The respondents were asked ‘whether they had contact with six key public services in their country in the previous 12 months: the police, the courts, health care, schools, identity documents and utilities’. They were then asked ‘whether they paid a bribe, gave a gift or did a favour in order to receive the services they needed’ (Transparency International 2019: 17).

- In the Sudanese context, land grabbing refers to large-scale land acquisitions by domestic and foreign actors, typically through purchases and leases, often marred by secrecy and legal manipulation to obtain and sell land (The Enough Project 2017: 33). Through acts of dispossession and forced displacement, these moves result in wealth extraction and securing patronage (The Enough Project 2017: 32).

- Please refer to the section on the anti-corruption commission for more details.