Query

Please provide a summary of the key corruption risks and potential mitigation measures for informal settlement upgrading, including a focus on the case of Namibia.

Introduction: Informal settlement upgrading

As part of the 2030 Agenda, Sustainable Development Goal 11 carries the aspiration to ‘make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’. The United Nations highlights that in 2022, 24.8% of the world’s urban population lived in slums or slum-like conditions (United Nations n.d.). Target 11.1 of the agenda reads ‘by 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums’ (United Nations n.d.).

Adopting the term informal settlements instead of slum,4ac2d7af2ae8 this Helpdesk Answer explores this ‘upgrading’ process and surveys the available evidence on its relationship with corruption and anti-corruption. The remainder of the introduction focuses on what characterises informal settlements and what is meant by upgrading. The following section outlines the different corruption risks that can undermine upgrading and identifies actual allegations and cases of corruption in the sector as highlighted in the literature. For the purposes of this section, it should be noted that a range of concerns can be precipitated by informal settlement upgrading – notably a lack of adequate consultation with dwellers – and that these may not per se amount to corruption, although they may contribute to heightened corruption risks. The last section explores the different measures that can be used in upgrading processes to mitigate against these risks. Finally, an annex gives a brief overview of the situation in Namibia and how these dynamics play out there.

Informal settlements

According to one estimate, around a quarter of world’s total urban population lives in informal settlements (The Shift 2021). This is even more pronounced in sub-Saharan Africa where up to 60% of the urban population lives in informal housing (Zinnbauer 2020:4). Zinnbauer (2020: 4) argue it is important to recognise that informal settlements take different forms across regional contexts; for example, in sub-Saharan Africa, informal settlements typically constitute small-scale rental units owned by absentee landlords, whereas in China, they may take the form of large-scale housing complexes built on the initiative of property developers and local officials but without the necessary licences. In some Latin American countries, it has been found that informal settlements take the form of dwellers illegally or irregularly occupying public, communal or private land (Fernandes 2011:4). Atkinson (2024: 2) notes that while informal settlements often develop at the periphery of urban areas, they can also be located directly in city centres.

Atkinson (2024:2) notes that ‘even though informal settlements have been studied for decades, there is still no universal definition of the term’. Instead, informal settlements are often identified via key characteristics. An expert group meeting convened in 2002 by UN Habitat (UN Stats 2021) identified such characteristics, which have become a widely used reference point:

- lack of access to improved water sources

- lack of access to improved sanitation facilities

- lack of sufficient living area

- lack of housing durability

- lack of security of tenure

The first four of these cover traits that are typically associated with informal settlements such as overcrowding, inadequate local infrastructure and services, and poor quality housing structures. These make informal settlements vulnerable to the effects of natural disasters; for example, informal settlements tend to be particularly at risk of flooding (Atkinson 2024:2). The fifth – security of tenure – refers to the fact that dwellers of informal settlements often lack or have an uncertain legal basis for residing there, which can make their living situation highly precarious (Atkinson 2024: 3).

The UN special rapporteur on the right to adequate housing (hereafter the UN special rapporteur) explains that ‘informality is a response to exclusionary formal systems’ (United Nations General Assembly 2018). For example, groups of people may migrate to an urban area in search of employment or as a result of displacement, but the formal housing system is unable to accommodate them. This necessitates the development of a subsidiary housing system along with informal businesses arising to respond to needs for water, sanitation, electricity and other needs (United Nations General Assembly 2018). This can eventually create cleavages between informal settlements and other urban areas, meaning that urban development measures, such as codified planning systems, may only serve the higher income areas (Nkula-Wenz et al. 2023:28).

Atkinson (2024:2) further explains that informal settlements often develop incrementally, due to poor urban planning and volatile housing markets reducing affordability for low-income earners. Alemie et al. (2015: 293) point out that a lack of a pro-poor housing policy, political transitions and a lack of enforcement of land management rules can all also contribute to the development of informal settlements.

On top of this, Baye et al. (2023) explain that corruption can act as a driver of informal settlements. They document the case of Woldia Township in Ethiopia, where corruption resulted in uncontrolled land development. Local government officials reportedly facilitated the conversion of rural agricultural lands to residential use without legal grounds, knowing they could extract more rents from dwellers in a densely populated area than from farmers, but also meaning these dwellers’ tenure status was unclear (Baye et al. 2023:11). Corruption may result in landlords being able to acquire permits to develop housing and extract rents from informal settlements on substandard land, for example, in areas vulnerable to flooding (Sanderson et al. 2022).

Furthermore, day-to-day operations in informal settlements can be shaped by corruption. For example, in the Zandspruit informal settlement in Johannesburg, local elites preside over rental and tenure governance structures and may exploit their position to extract fees from dwellers (Dawson 2014: 525-6). Indeed, the fact that dwellers often do not have legal tenure can expose them to forms of corruption and extortion(Cities Alliance n.d. b). On account of their socio-economically disadvantaged status and lack of tenure security, individuals living in informal settlements may have few options to challenge eviction orders or achieve redress (Transparency International and Equal Rights Trust 2024: 82-83).

Historically, governments often addressed informal settlements through evictions and ‘clearances’, especially where sites occupied by informal settlers were selected as the focus of infrastructure development projects (Christensen 2024: iii). Cities Alliance (n.d. a) argues that, while relocating an informal settlement population can be necessary in situations where the land is environmentally unsafe, evictions normally occur when local authorities want to ‘turn the land over to developers or other vested interests’.For example, Zimbabwean authorities, with the involvement of urban planners, forcibly evicted 700,000 people from informal settlements in 2005 and told them to return to the area of their ‘rural origins’, creating widespread displacement (Nkula-Wenz et al. 2023:29). Christensen (2024: iii) states that the harmful and ineffective consequences of clearances has led to the emergence of more holistic policies ‘which, in addition to the physical upgrading of the informal settlement, considers income generation, provision of social services, environmental, economic, and political sustainability, governance, and community cohesion’.

Upgrading

Satterthwaite (2012: 206) holds that upgrading695061aba141 can loosely be described as ‘a set of measures to improve housing conditions in the informal settlements or “slums” that house a high proportion of urban dwellers in all low-income and most middle-income nations’. He elaborates that the term normally connotates an ‘official acceptance of the rights of the inhabitants in informal settlements to live there and to receive government infrastructure and services’. However, in some contexts, the term upgrading is also used when inhabitants are relocated because, for example, in situ improvements are not possible or the land is not suitable for human settlement (National Upgrading Support Programme 2015: 2-3).

Upgrading processes typically seek to address the different characteristics of informal settlements described above. According to the Cities Alliance, upgrading measures ‘tend to include the provision of basic services such as housing, streets, footpaths, drainage, clean water, sanitation, and sewage disposal’. Notably, many upgrading interventions do not deal with housing construction as this may be seen as the imperative of the informal settlement residents; however, they can still be supported in this endeavour through access to finance, construction materials and capacity building (Cities Alliance 2022: 9-10). Furthermore, upgrading can also contribute to greater resilience against natural disasters through, for example, protecting informal settlement populations from landslides in Medellín, Colombia (Smith et al. 2018).

Moreover, the Cities Alliance (n.d. a) stresses that upgrading is about more than infrastructure improvement, and it should encompass the economic, social, institutional and community activities needed to turn an area around by, for example, facilitating access to education and healthcare, as well as legalising or regularising properties to secure land tenure for residents (Cities Alliance n.d. a). The Cities Alliance (n.d. b) argues that secure tenure is at the centre of upgrading as it makes it more likely residents will invest in their houses and living conditions.

In light of the variety of measures, the Cities Alliance (2022: 9) differentiates between minimalist and more comprehensive interventions, noting that some governments will aim to maximise the target population’s access to basic infrastructure, while others take more holistic approaches that combine infrastructure improvements with other policy measures such as enhanced legal and environmental protection. Similarly, Satterthwaite (2021) notes that upgrading can take many forms demonstrating different levels of ambition and offers a typology to describe these (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Satterthwaite’s classification of different forms of informal settlement upgrading

|

Form of upgrading |

What it involves |

|

Upgrading that is actually eviction |

Pushing residents out of their homes and settlement and rebuilding but with residents not able to access 'upgraded' dwellings |

|

Rudimentary upgrading |

Some very basic interventions such as community taps and public toilets |

|

More complete upgrading |

Piped water and toilets in each home, electricity, some reblocking, paved access roads, sometimes sewers and drains. Little consultation with residents |

|

Comprehensive government-led upgrading |

Legal land title, full range of infrastructure and services (including neighbourhood level such as drainage, street lighting and solid waste collection), support for housebuilding and improvement and for enterprises. Consultation with residents |

|

Comprehensive community-led upgrading |

As above but with community control as exemplified in upgrading programmes supported by CODI and SDI affiliates |

|

Comprehensive community-led upgrading with resilience lens |

As above but with greater attention to assessing and anticipating future risk levels |

|

Transformative upgrading |

As above with attention to low carbon footprint |

Source: Satterthwaite 2021

He explains that the extent of upgrading often depends on the level of government backing. The first three forms are usually managed by local government authorities while the fourth form necessitates stronger commitment from the national government (Satterthwaite 2021). The remaining three forms are also backed by the national government, but implemented under the leadership of the community and with due attention to environmental and other factors. They note that, while upgrading may be driven by individuals and communities based in the informal settlement, the process may also be led through externally administered programmes which may or may not support the interests of dwellers (Satterthwaite 2012: 208).

Nuhu et al. (2023: 36) notes that, while upgrading has become widely endorsed in African countries, the governance challenges associated with this have been relatively understudied. Despite the well intentioned aspirations of upgrading, it may lead to distorted outcomes. For example, given that people residing in informal settlements are rarely a homogenous group, Atkinson (2024) warns that ‘upgrades may re-create marginalisation for some groups’. Furthermore, Mwamba and Peng (2020) flag that, if not well managed, upgrading may lead to high rents, gentrification and displacement of the original residents (Mwamba and Peng 2020). The following sections explore to what extent corruption can undermine upgrading processes and lead to undesired outcomes.

Corruption risks

This section will identify and analyse the corruption risks associated with informal settlement upgrading. The consequences corruption can have on upgrading interventions can be severe, including making the projects more expensive, reducing international financial assistance for such goals and damaging the overall integrity of the efforts, including the target community’s participation and trust in them (The Shift 2021; UNGA 2018: 8).

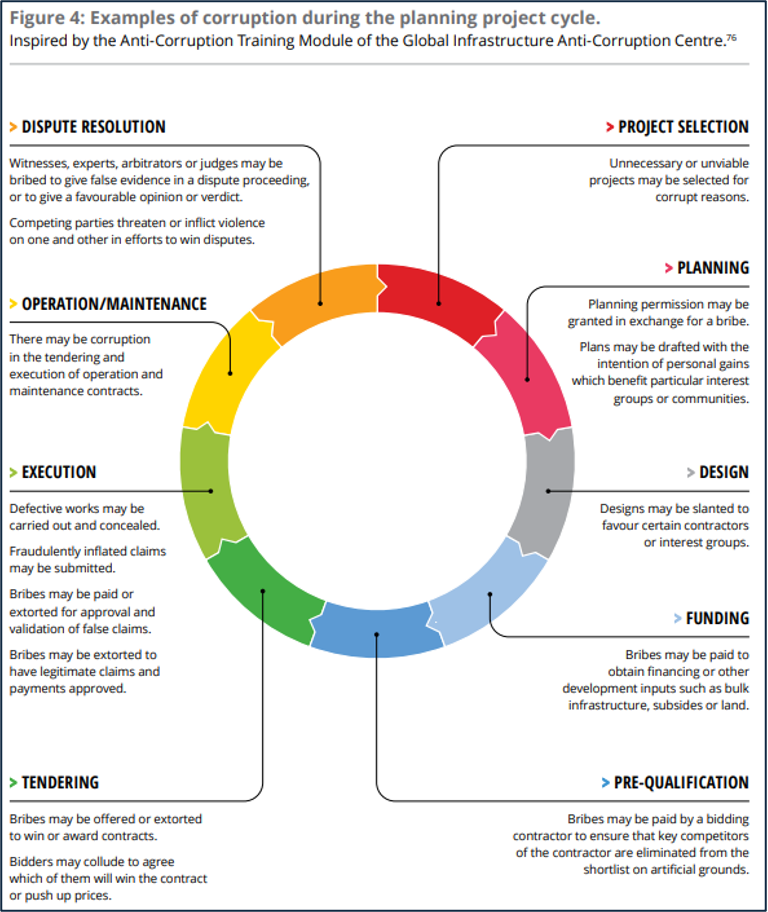

Many of these corruption risks overlap with the general risks associated with infrastructure projects within the urban development context more widely. Nkula-Wenz et al. (2023: 25) give an overview of such risks across the project cycle, encompassing the stages of project selection, planning, design, funding, pre-qualification, tendering, execution, operation/maintenance and dispute resolution (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Examples of corruption during the planning cycle of infrastructure projects

Credit: Source: Nkula-Wenz et al. (2023: 25)

Additionally, Nkula-Wenz et al. (2023:2) identify four main drivers behind these corruption risks in such projects:

- the high financial stakes of decisions that influence property and land values and that determine the viability of large-scale developments.

- the competing needs of various actors (state bodies, private sector interests and citizen groups)

- the pressure applied by special interest groups (developers, landowners and political parties)

- the highly discretionary nature of the decision-making process

The literature suggests that similar overarching dynamics are at play in informal settlements. For example, the land on which informal settlements are located often has a high real estate value (Cities Alliance 2022: 20). Furthermore, Atkison (2024) explains that state and non-state actors may benefit from the status quo in informal settlements if it serves their interests and allows them to engage in corruption and collusion in order to resist improvements.

However, these dynamics can also persist through upgrading processes. Describing ‘slum redevelopment’, Bhide and Solanki (2016) argue that a range of state and non-state actors – such as politicians, developers, organised criminal groups, police and non-governmental organisations – may all try to take control in processes that affect informal settlements and take up roles as intermediaries to determine which residents gain access. Alluding to urban planning processes more generally, Lee-Jones (2017:1) notes that the local decision-makers whose role is to resolve such competing interests are often afforded a high level of discretion.

That being said, Zinnbauer (2020: 11) cautions that it can be difficult to measure and compare the incidence of street-level corruption in informal housing given the lack of evidence, diversity of the forms of housing and the typically fragmented policy and legal frameworks. Accordingly, he emphasises the risks of corruption that affect informal settlements can vary across contexts.

Corruption involving private sector actors

While upgrading processes are usually undertaken under the leadership of national or municipal authorities, it is common that private sector actors are enlisted either as investors or to carry out related services.

Satterthwaite (2012: 211) notes that authorities around the world often cite upgrading initiatives which took place in Singapore, Dubai and Shanghai as best practices with strong private sector involvement. However, if risks are not managed, informal settlement upgrading processes can be captured by private sector actors, resulting in unfair competition and ultimately to the detriment of beneficiaries. ‘Regulatory capture’ can occur where authorities take decisions that unduly favour the interests of a private sector actor, such as when deciding to grant a permit or not (Lee-Jones 2017: 3-4). In the context of urban development, property developers or private actors operating in the real estate sector often play an outsized role. Zinnbauer (2019) explains that such developers may bribe local politicians, support them with campaign financing or give them ownership stakes in initiatives to bypass vetting procedures and gain access to valuable urban land.

SRS in Mumbai

In the 1990s, a public-private partnership programme known as slum rehabilitation (SRS) was introduced in Mumbai where horizontal housing was converted to vertical buildings and the rights to reclaimed land would be made available to property developers for new housing projects they would finance, but with the aim of securing a profit (Doshi and Ranganathan 2017:9). While the programme contained certain safeguards – such as requiring approvals from the local community and the Slum Rehabilitation Authority – Bhide and Solanki (2016) argue that property developers held excessive control over the process and took decisions to maximise profits. Furthermore, they allege developers engaged in document forging and bribed local politicians and bureaucrats and organised criminal groups to ‘capture the slum’. Similarly, Doshi and Ranganathan (2017:9) flag evidence that Slum Rehabilitation Authority officials had received millions of rupees in kickbacks, eligible residents had been unfairly omitted from beneficiary lists and even that false charges were levelled against dwellers who refused to comply with the programme outcomes. Bhide and Solanki (2016) argue that the programme did not achieve its stated goals but instead resulted in increased density of the informal settlement areas, internal displacement and an appreciation in rents.

The real estate sector is often used to launder illicit gains, aided by opaque ownership schemes and a lack of regulation (GIZ 2020), and upgrading can present similar vulnerabilities. For example, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (2017) reported that Indian financial crime authorities investigated a former chairman of the Maharashtra Housing and Area Development Authority on suspicion of orchestrating a money laundering scheme via an upgrading process in Mumbai. The chairman reportedly arranged for development contracts to be awarded to front companies he and other partners owned with the aim of laundering money.

In other cases, private actors may have a monopoly over the public services informal settlement residents rely on. For example, in New Delhi local politicians, landlords and a ‘water mafia’ reportedly colluded to ensure only they could provide water via trucks to the informal settlement (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017). The special rapporteur highlights that monopoly practices can lead to unaffordable fees and recommends that access to water, toilets and other necessities, regardless of residents’ ability to pay, should be a priority in upgrading (UNGA 2018: 8).

Corruption involving political actors

As alluded to, political stakeholders, especially local authorities, are often the main facilitators of informal settlement upgrading. For example, they hold authority over planning regulations and policy instruments, the issuance of building permits and compliance measures (Lee-Jones 2017:2). The Cities Alliance (2022: 16) cautions that providing tenure security for residents living on high value land can be difficult because ‘control of land is often connected to political patronage and corruption’. This discretionary power may be exploited for self-serving aims and the interests of their in-groups.

Political stakeholders often hold active interests in these processes. For example, with reference to Kibera in Nairobi, Zinnbauer (2020: 16) states that a large majority of informal settlement residents pay rents to landlords who live offsite and notes that more than half of these landlords are believed to be government officials or politicians.

Furthermore, Nuhu et al. (2023: 44) explain that national and local officials may abuse their position as the owners of upgrading processes for political benefits. Zinnbauer (2020: 5) notes that cities tend to have ‘sufficient socio-economic scale and diversity to support several competing clientelistic networks’, leading to generally ‘more intense political competition than rural settings’. The typically high population density of informal settlements is arguably even more prone to clientelist tendencies, where political actors may engage in forms of corruption that benefit their voter base, especially during their electoral cycles. Auerbach and Kruks-Wisner (2020 1) carried out a survey on people living in poverty in northern India and found that those living in informal settlements were much more likely to report the presence of ‘political brokers’ compared to those living in rural areas.Nuijten (2013) analysed an upgrading project in Recife, Brazil in which dwellers were moved from purportedly unsafe shacks close to a new housing state. They found that the increased contact between state officials and residents during the project encouraged personalised politics and reinforced patronage relationships.

Bhide and Solanki (2016) describe how, over decades in Mumbai, political actors have promoted the concentration of different communities in informal settlements, such as Muslims and members of the Dalit minority, to assert electoral support. In their study of informal settlements Cape Town, Ehebrecht (2014: 122-123) documents reported attempts by a local branch of the African National Congress (ANC) to take control of an upgrading project.

Klopp and Paller (2016) describe how some politicians in Kenya instrumentalise have used insecurity to mobilise voters by promising informal settlement dwellers more security. Similarly, a study by Baye et al. (2023: 16) on informal settlements in Wolida, Ethiopia found that politicians instrumentalised the prospect of regularisation to gain votes. However, political actors may not always uphold their electoral promises. Some respondents to a study of an upgrading project in South Africa related that ‘promises made at election time were later forgotten’ (Isandla Institute 2024: 30). However, it is important to note that a range of extraneous factors other than corruption may also be behind failures to deliver on electoral promises.

It is important to note that manifestations of clientelism can vary across contexts. While not specific to informal settlements, Goodfellow (2015) applies a ‘political settlements’2d4f2be8a316 approach to contemporary urban development in Eastern African settings in order to show how different variations of clientelism can manifest and that application of laws and rules is carried out inconsistently in order to cater to clients. However, this differs between Kampala, for example, where clientelism takes a more competitive form in which rules are subject to alteration, and Kigali where clientelism is more formalistic in nature and rules are largely complied with.

Distorted selection of beneficiaries

In upgrading processes, those with influence over decisions on the identification of beneficiaries and allocation of funds to them may not perform their role equitably but instead give favourable treatment to a subset of informal settlement residents. This can include national and municipal political figures or individuals nominated to represent the interests of the wider informal settlement community.

Informal settlements can play host to allegiances based on different identity factors, such as political, religious and ethnic. Marx et al. (2019) analysed rent prices and lower quality housing (measured via satellite pictures) of the Kibera informal settlement in Nairobi and found evidence of the role ethnic patronage. They found that where the local authority (‘chief’) was of the same ethnicity as the landlord, rents were likely to be higher and quality of housing lower for residents, but where the chief shared the ethnicity of the residents, they were more likely to enjoy lower rents and better housing. Similarly, Taylor (2010) describes an informal settlement relocation intervention in Kenya where residents alleged ‘houses went to allies of the local chief’ and that when a representative of the resident community tried to challenge this, police planted narcotics and arrested him.

Giurfa (2024: 29) highlights the important role of community leaders in informal settlements in Lima in liaising with authorities, but repeated allegations that these leaders sometimes advantage of their position and ‘[scam] residents on project fees or colluding with municipal officials for supposed improvements in the informal settlement for their financial gain’.

Kwa-maji Urban Development Project

In the context of upgrading, Rigon (2014: 258-60) highlights that the programming often treats the local community as a homogenous entity and fails to recognise that each community contains its own power structures where different interests are contested. They describe how a residents’ committee was established to represent the local community as part of an upgrading project in Kenya known as the Kwa-maji Urban Development Project, but that the election of this committee resulted in a disproportionate number of local landlords becoming committee members compared to tenants, who may have felt compelled to vote for their landlords (Rigon 2014: 264-65). Rigon (2014: 279) argues this created a risk that the project would benefit groups with a higher income instead of the intended beneficiaries.Furthermore, the committee was charged with counting the beneficiaries of the upgrading measures, but bias and incomplete data reportedly contributed to a failure to list many deserving beneficiaries (Rigon 2014: 268). For example, the practice of listing only the man as a beneficiary for multi-person households meant many women were not recorded as potential beneficiaries (Rigon 2014: 269).

Bribery and extortion

Actors implementing upgrading processes typically need to comply with multiple administrative procedures, such as obtaining permits for registration, zoning, construction and other approvals. Depending on the integrity of local actors and how bureaucratic the procedure is, this can expose them to bribery and extortion attempts (Lee-Jones 2017:4). For example, Ehebrecht (2014: 157) describes how local officials may ask for bribes to process land registration requests. Similarly, Klopp and Paller (2016) found in their study of informal settlements in Kenya that bribes are often demanded to obtain a building permit.

Informal settlement dwellers may also contend with demands for bribes when trying to access public services (see Tvedten and Picardo 2018: 7), and this risk should be acknowledged when trying to increase the reach of basic services as part of upgrading. For example, two different studies based on the same fieldwork found that significant proportions of dwellers in informal settlements in Karachi had been asked for bribes when visiting proximate police stations and hospitals respectively (Ahmed and Ahmed 2012a; Ahmed and Ahmed 2012b). Similarly, in Maputo, Mozambique, external small firms reportedly recruited people to collect fees from informal settlements for waste management services that had ‘already been paid for through regular fees, and which should be free’ (Tvedten and Candiracci 2018: 10). In contrast, in South Africa, the City of Cape Town subcontracted waste collection responsibilities to private companies who claimed they were subject to extortion rackets that prevented their trucks from accessing informal settlements (Isandla Institute 2024: 22).

Embezzlement and misappropriation

Depending on the scope, upgrading interventions can require significant financial investment and funds to be allocated for multiple expenses. This entails financial management vulnerabilities and with that the risk that funds are embezzled or assets misappropriated.

For example, a project based in the Kibera informal settlement in Nairobi called the National Youth Service (NYS) Slum Upgrade Initiative was ended after tens of millions of dollars reportedly went missing (Mwanza 2018). In South Africa, the auditor general of an upgrading project in the Alexandra Township during the COVID-19 pandemics found that the poor level of coordination and accountability between national government and municipalities concerning the allocation of budgets and the tracking of expenditure led to misappropriation risks. These were reportedly heightened given the urgency of the deliverables and the absence of preventive measures built into the project (Phakathi 2021:81-82).

Beyond funds, tangible assets that are acquired under upgrading processes can also be at risk. In India, an investigative journalism campaign into a scheme launched in Delhi in 2022 uncovered reports that local officials and middlemen were, through the use of fabricated documents, illegally selling flats intended for the underprivileged to affluent buyers (Ahuja 2024).

Opacity

Even where no specific allegations are made, the lack of transparency or opacity in upgrading processes can lead to widespread rumours or perceptions of corruption, which ultimately undermine public trust in the process (Prouse 2020; Doshi and Ranganathan 2017; De Feyter 2015). De Feyter (2015) explains that when informal settlement residents’ access to information is limited, they may be compelled to turn to ‘rumours’ – including about corruption – as an alternative source of information.

Several examples show how transparency gaps can undermine upgrading processes. In Mumbai, representatives of informal settlement dwellers complained about an NGO that had been commissioned to facilitate resettlement but had imposed fees on residents without giving explanations on what the fees were for (Doshi and Ranganathan 2017:9). Nuhu et al. (2023:41) describe how residents lost confidence in an upgrading process in Tanzania after the private company contracted refused to disclose information and updates. The community leaders representing the residents also expressed frustration that they had been held accountable for bad decisions the private company had made.

The Isandla Institute (2024: 30) describes how rapid response plans in South Africa to de-densify informal settlements as a measure during the COVID-19 pandemic were received poorly by residents who cited a lack of transparency and expressed fears that the plans masked an attempt to evict them. Regarding South Africa’s national-level policy on upgrading, Van der Westhuizen (2017: 6) argues that it also lacked sufficient transparency guarantees on the financing aspects of upgrading.

Mitigation measures

While upgrading continues to be widely viewed by the international community as an optimal approach to improving conditions in informal settlements, there has been increasing recognition that upgrading should be accompanied by safeguards to mitigate against corruption risks. The special rapporteur (UNGA 2018: 15) made a strong call in this respect:

‘Measures must be put in place to prevent corruption at all stages of upgrading, from land acquisition, to tendering of contracts, to the allocation of upgraded housing units. Rigorous independent oversight of all aspects of the upgrading process, including all public-private partnerships, should be put in place and, where appropriate, communities should be afforded oversight and decision-making authority over resource allocation and anti-corruption measures.’

Measures contained in more general frameworks on upgrading can also feed into anti-corruption efforts. The Cities Alliance (n.d. b) has promoted ten principles for a slum upgrading process:

- accept and acknowledge slums and their importance

- political will and leadership makes slum upgrading possible

- include the slums in the city’s plans

- mobilise partners

- provide security of tenure

- plan with, not for, the slum communities

- ensure continuity of effort over time and institutionalise the programme

- allocate budget, design subsidies, mobilise public and non-public resources

- find alternatives to new slum formation

- invest in community infrastructure

This section will provide an overview of some of these measures and refers to best practice case studies. However, as Zinnbauer (2020: 26) notes, upgrading or formalisation strategies for informal settlements are generally highly context specific, meaning a one-size-fits-all approach should be avoided.

Integrity

As discussed above, corruption risks in upgrading largely emanate from the abuses of power by responsible authorities, suggesting a need for promoting greater standards of integrity.

These can be grounded at the national level. For example, the department of human settlements which oversees many upgrading processes in South Africa has its own anti-corruption and fraud strategy, a procedure to prevent conflict of interest in procurement processes, obligatory financial disclosures for staff and corruption awareness training (Department of Human Settlements, Republic of South Africa 2023: 81-82). However, it also requires investment at local government levels where officials often manage upgrading processes but may receive less oversight and public scrutiny. Furthermore, Zinnbauer (2019: 4) argues that the professional urban planning community have the potential to act as agents of integrity in the sector. Their expertise-driven approach can contrast the self-interested approach of other actors. The Cities of Integrity project was implemented in South Africa and Zambia to develop professional communities of urban planners along these lines.

Risk assessment and management

Risk assessment and management should be an integral part of upgrading interventions. More generally, Mwamba and Peng (2020) argue it is also important to assess the local conditions of the target informal settlement and the unique needs its residents have, given that informal settlements are not homogenous. To avoid unintended consequences, the Isandla Institute (2024: 34) recommends that the different economic interests that can affect upgrading should be thoroughly assessed in advance, such as the rental and real estate markets. Similarly, Zinnbauer (2020: 24) recommends that urban development practitioners undertake an assessment of preexisting informal and formal arrangements to identify risks of abuses of power. In this regard, a political economy analysis can help shed light on potential competing political interests shaping the local environment where the intervention will take place.9011359b7611

As with other project based interventions often backed by donors, corruption risk management approaches can be adopted to ensure that the upgrading managing team regularly assesses risks and carries out audits of finance and other key operational factors (U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre n.d.). Day-to-day monitoring of a project should involve both internal and external stakeholders. For example, special committees were established to monitor upgrading interventions in Medellín, Colombia, composed of the local community, the construction companies, auditors and the project’s technical team (Cities Alliance 2022).

Furthermore, a risk-based approach can extend to ensuring that national and municipal actors carry out due diligence when assessing all potential contractors and implementing partners by, for example, considering prior records and performance history (Bloomberg Cities Network 2022).

Oversight and accountability

Measures should be integrated to ensure independent oversight of upgrading processes and facilitate accountability for where transgressions occur. Guaranteeing the independence of such mechanisms is important, given the potential complicity of state figures in corruption schemes, as discussed above

Civil society and community based organisations can play an oversight function. In 2014, the Social Justice Coalition conducted a community based audit that involved mapping the provision of public toilets in informal settlements in Cape Town (Nkula-Wenz et al. 2023:60). Nuhu et al. (2023: 38) describes the enhanced role community leaders play in upgrading efforts in Dar es Salaam, including overseeing the companies working on service provision in their locale.

Calls have also been made for states to implement independent oversight mechanisms to monitor all aspects of upgrading (The Shift 2021). In South Africa, for example, the City of Cape Town has established an office of the city ombudsman, which is able to receive and process complaints related to the performance of the city in the execution of its powers and functions, including allegations of corruption (Isandla Institute 2020). Furthermore, at the national level, there even exists a human settlements ombudsman, which processes complaints and conducts investigations into the governance of informal settlements (Isandla Institute 2020: 31). The special rapporteur highlighted as a good practice the role the Kenya national commission on human rights took up to oversee the allocation of upgraded units to the residents of the Kibera informal settlement (UNGA 2018: 6).The special rapporteur recommends that monitoring and oversight bodies be granted access to the information they need, be adequately resourced to carry out consultations, publish findings in accessible formats, and it should be ensured that all levels of government be required to respond promptly to the recommendations or concerns of monitoring bodies (UNGA 2018: 18).

In terms of accountability, the Isandla Institute (2024: 19) argues that government officials and any nominated community leaders should be expected to take responsibility for their actions and report accordingly in order to foster and improve the social compact with the wider local community.

More official pathways to accountability can also be facilitated. In Tanzania, community leaders reportedly flagged alleged corruption in an upgrading process to members of parliament, who in turn brought it to the attention of the responsible minister who said it would be investigated (Nuhu et al. 2023: 44). In Kenya, informal settlement dwellers initiated lawsuits to challenge what they argued were unfair allocation decisions made under an upgrading programme (Mwanza 2018).

However, the precarious legal status of many residents, combined with their general vulnerability, means that corruption often goes unchallenged (UNGA 2018: 15). Accordingly, the special rapporteur recommends that, as part of upgrading, complaints procedures should be established to hear directly from residents about problems, ensure respect for their rights and implement rights-based dispute resolution procedures (UNGA 2018: 18).

Transparency

Integrating transparency measures into upgrading processes can help address concerns around opacity and make corruption risks easier to detect.

Nuhu et al. (2023: 40) argue in favour of facilitating widespread access to information regarding land ownership and upgrading processes, and argue this should be grounded in legal and policy frameworks. For example, publicly accessible beneficial ownership registries with accurate and updated information can be used to locate information about the ownership of real estate assets (GIZ 2020). Zinnbauer (2020: 31) argues that transparency in urban development would benefit most from ‘accessible and timely public disclosure of information on:

- beneficial ownership of companies active in the local economy, and beneficial ownership of land and property holdings

- municipal budgets and major contract

- the assets, incomes, and interests of senior civil servants and policymakers’

Transparency measures can serve to foster greater trust and local ownership. In an upgrading process in Medellín, Colombia, deliberate transparency measures were included; for example, it was ensured that from the outset that all hired companies and oversight services had to meet with a committee representing the community with the aim of establishing harmonious relations (Cities Alliance 2022).

Participatory decision-making

Decision-making mechanisms that enable the participation of the affected community are integrated into many upgrading processes to ensure that the intervention addresses their needs and achieves buy-in. However, such mechanisms can also facilitate checks and balances and function as an important anti-corruption safeguard. Nevertheless, given the risks described above, these processes can be designed in a way that recognises existing inequalities, power structures within the local community and the potential abuse of participation mechanisms to seek favourable treatment.

Alemie et al. (2015) describe how participatory decision-making helps bring competing and diverse interests to the fore early in the process and can facilitate the resolution of differences. According to Isandla Institute (2024: 19), participatory decision-making can be best achieved through deliberative engagement, where ‘outcomes or solutions are not predetermined but subject to consideration and negotiation between informal settlement residents and the municipality (with possibly other stakeholders drawn into the process, as and when appropriate)’. Nuhu et al. (2023: 44) argue in support of a consensus based process to prevent the risk of political interference. Ono and Adrien (2024) describe how a community management organisation organised negotiations between residents of an informal settlement in Kigali, which led the community to reach a consensus on which infrastructure facilities should be prioritised.

The Ng’ombe Upgrading and Poverty Reduction Project was an upgrading intervention implemented by the civil society organisation Human Settlements of Zambia (HUZA) in an informal settlement in Lusaka (Mwamba and Peng 2020). The project included the establishment of a resident development committee which coordinated a participatory needs assessment to determine the priorities of the residents (Mwamba and Peng 2020). HUZA reportedly designed the project around these needs by, for example, allocating funds to the construction of a health centre, a skills training centre and provision of a micro-credit scheme (Mwamba and Peng 2020). In another upgrading process in Medellín, Colombia, companies were obliged to hire locals to offer new employment opportunities (Cities Alliance 2022).

The special rapporteur (UNGA 2018: 17) makes several recommendations on ensuring the right to participate, including providing informal settlement residents with accessible information regarding the upgrading and allocating of resources and disbursements for expenses to support the participation of residents.

Annex: Informal settlement upgrading in Namibia

This annex gives a brief overview of informal settlement upgrading in Namibia. In 1991, only 27% of Namibia’s populations resided in urban areas. However, rapid urbanisation has occurred, meaning this is expected to increase to 75% by 2030 (Development Workshop Housing 2019: 8). In 2023, the national statistics agency estimated that 28.7% of all households in Namibia were informal housing, of which 40.2% were in urban areas (Namibia Statistics Agency 2024: 63). Informal settlements are present in long urbanised areas such as the capital Windhoek, but also have emerged in areas that were previously largely rural (Remmert and Ndhlovu 2018: 24)1e9950ad3e95.

Some existing informal settlements – such as Katutura township – originate from apartheid policies when Namibia was administered as South-West Africa while under South African occupation between 1960 and 1996 (Remmert and Ndhlovu 2018: 13). The forced relocation of Black subpopulations and segregation along ethnic lines resulted in the emergence of these settlements (Melber 2023).

Informal settlements in Namibia are confronted with many of the same issues described above. Christensen (2024: 141) states that many informal urban residents have low or no tenure security, meaning they can be vulnerable to eviction without compensation. In a study of three informal settlements, Larsen and Augustus (2018: 77) found evidence of a lack of basic services (water, sanitation and electricity), and reported incidents of crime and violence and residents’ general mistrust of local and national authorities. For example, many dwellers they interviewed expressed the sentiment that politicians and local authorities only made themselves visible during elections (Larsen and Augustus 2018: 88). The authors (Larsen and Augustus 2018: 88) also expressed concern about Namibia’s reliance on private actor engagement in responses to informal settlements, which carry a risk of leading to higher rental prices and exacerbating the existing socio-economic inequality. In 2024, informal settlement dwellers living in Okahandja launched protests against the local municipality regarding an upgrading initiative which they perceived had failed to deliver and requested information be shared on how funds were being spent (Informante 2024). In 2025, theOtjomuise informal settlement inWindhoek experienced flooding, causing severe damage to the housing infrastructure (Kangumine 2025).

While there is little evidence of corruption in informal settlement upgrading projects in Namibia, there have been several high-profile cases involving housing initiatives targeting low and middle-income residents more broadly.

In a case from 1996 known as the Single Quarters Scam, up to NAD6.6 million (around US$1.5 million in 1996) were allegedly embezzled from an urban redevelopment for the aforementioned Katutura township (Kuteeue 2003).

The National Housing Enterprise (NHE) is a state-owned company and derives its mandate from NHE Act No 5 of 1993. It describes itself as ‘providing housing needs to low and middle-income inhabitants of Namibia and financing of housing for such inhabitants’ (National Housing Enterprise n.d.). In 2013, the NHE launched the mass housing development programme (MHDP) to construct 185,000 housing units by 2030 to address the nation’s housing shortage. However, it faced allegations of financial mismanagement and tender irregularities, which led the government to suspend it in 2015 (Remmert and Ndhlovu 2018: 27).

A similar housing project valued at NAD3.5 billion launched in the early 2010s was halted in 2017 after allegations emerged that contracts were inflated and tenders were awarded unfairly, including on the basis of nepotism (Matheus 2024). This reportedly contributed to poor quality housing without access to basic amenities and inflated prices, meaning many units were unoccupied. In a separate incident in 2019, the former minister of education, arts and culture was convicted on corruption charges, following evidence she had removed the names of beneficiaries for new state-funded houses and replaced them with those of her relatives (Rickard 2019).

Immanuel (2014) describes how public officials awarded tenders for a project to construct 600 housing units in Swakopmund to private sector actors who only took on middlemen roles and subcontracted all tasks but still acquired substantial profits. Given the reliance on private actor engagement in state responses to informal settlements in Namibia, similar corruption risks could undermine upgrading efforts.

In Namibia, there are policies in place to support upgrading, as well as dedicated actors working on the topic. The upgrading agenda is largely driven at the national level by the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform (MAWLR) (Christensen 2024: 177) and often implemented at the local level by municipal governments. MAWLR recently opened a process for the public to report corrupt practices within the land sector directly with the office of the minister (Bala et. al 2022: 8). Furthermore, the National Alliance for Informal Settlement Upgrading (NAISU) is ‘a partnership to scale up security of tenure and housing opportunities through co-production between organised communities, local and regional authorities, central government, and universities’ (Integrated Land Management Institute 2021: 4).

In the 1990s, the government began to roll out the flexible land tenure system, which set out to provide informal settlement dwellers with the opportunity to gradually increase their level of tenure security and thus upgrade their land (Larsen and Augustus 2018: 70). Under the system, dwellers could progress from a ‘starter title’ to a ‘land hold title’ and a ‘freehold titled deed’, all reflecting different gradations of land rights.a1a73b4ed205 The system achieved greater legal grounding when the Flexible Land Tenure Act (No. 4 of 2012) was passed by parliament in 2012 (Larsen and Augustus 2018: 70). The government of Namibia informed the special rapporteur that the Flexible Land Tenure Act of 2012 had streamlined the process and helped to provide security of title for persons who live in informal settlements (UNGA 2018: 11). However, other studies have identified some gaps in the system. Christensen (2024: 176) reports that many local CSOs found the urban planning procedures hierarchical and cumbersome, which led to significant delays.

Some studies have been commissioned to analyse upgrading processes in Namibia. Christensen (2024: 215) documents upgrading carried out in the Oshakati municipality. He notes that the reported low capacity of the municipal authority and the low number of available professional urban planners in the country led to delays in upgrading. However, Christensen (2024: 215) highlights the good practice of a database of plots, boundaries and rightsholders created by the authority. This was done with the aim of detecting unlawful transfers and preventing people from acquiring land beyond their allocation, which therefore carries an important anti-corruption function. He also highlights how a training of the management committee members and residents contributed to establishing a good relationship with the local authority and created a sense of trust and confidence between the parties, which should make it more likely for them to report illegal transfers (Christensen 2024: 217). Christensen (2024: 217) concludes that the MAWLR and municipal authorities must enhance monitoring and control of rights allocation and transfers to ensure that professional landlords or speculative property developers do not capture upgrading processes.

Another study by Ndalifilwa (2019) assessed how community participation was implemented during an intervention to formalise an informal settlement led by the Swakopmund municipality. They concluded the participation remained tokenistic and that, while information was shared, the municipality generally did not allow for inputs from the residents and noted the absence of ward committees and democratically elected community leaders. They recommended that the municipality adopt more detailed community engagement strategies in the future.

A 2018 study recommended that ‘national budgets for housing need to be administered in a more transparent manner, especially at regional and local levels, to improve accountability’ (Remmert and Ndhlovu 2018: 7). In recent years, Namibia has made strides in improving its legislative framework, such as such as the introduction of the Access to Information Act 8 of 2022,a929d8d662e1 which enables citizens to request access to information held by the Ministry of Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform (IPPR 2022:3).

While these are not featured heavily in the literature, future Namibian informal settlement upgrading projects may also benefit from the other mitigation measures set out in this paper, such as independent oversight mechanisms and risk management.

- While the term slum is still widely used, the UN special rapporteur on the right to adequate housing has stated a preference for the term ‘informal settlements’, holding that it is more in line with a human rights-based approach to housing because ‘slum’ is often considered pejorative and stigmatising (United Nations General Assembly 2018). Therefore, the term ‘slum’ is generally avoided in this paper, with exceptions for where it is featured in reproduced text from other sources.

- Instead of ‘upgrading’, other terms such as ‘redevelopment’, ‘regularisation’ and ‘formalisation’ may be employed. These terms can all carry different connotations depending on the context. For the purposes of this Helpdesk Answer, upgrading is used in a more overarching way to describe policy approaches which contrast with evictions and clearances.

- Goodfellow (2015) uses Mushtaq Khan’s (2010: 20) understanding of ‘political settlements’ which involves a ‘an institutional structure that creates benefits for different classes and groups in line with their relative power’.

- For an example of a political economy analysis approach applied to the urban development sector, see Tilitonse Foundation. 2019. Political Economy Analysis of Urban Governance and Management in Malawi.

- For a more detailed breakdown on the geographical distribution of informal settlements across Namibia, see p.64 of Namibia Statistics Agency. 2024. 2023 Population and Housing Census Main Report.

- For further details on the differences in land rights accorded by these titles and how the system operates in practice, refer to Christensen. 2024. Urban Land Tenure Security in Namibia: A Comparative Perspective.

- For an overview of the Act, see Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). 2022. Your Right of Access to Information: A Simplified Guide to Namibia’s Access to Information Act 8 of 2022.