How and why the anti-corruption court was created

In 2002, the (interrupted) 23-year reign of Didier Ratsiraka came to an end with the election of Marc Ravalomanana as president of Madagascar. The country signed the United Nations Convention Against Corruption and embarked on an ambitious reform agenda, including the establishment of an independent anti-corruption authority with investigative powers – the Bureau Indépendant Anti-Corruption (BIANCO). A ministerial circular further created the Chaîne Pénale Economique et Anti-Corruption (CPEAC), a special group of anti-corruption prosecutors and judges within the six provincial courts of Madagascar.776665d7848a

However, evaluations from 2009 and 2014 conducted by the country’s national anticorruption institutions (MinJus and CSI; Comité de Pilotage) found the CPEAC to be lacking effectiveness and independence. In particular, the Malagasy judiciary – including the CPEAC – was generally regarded as being very corrupt and prone to executive interference. The relatively independent BIANCO was thus lacking a similarly independent court that could turn its investigations into effective prosecutions and convictions. Indeed, BIANCO data indicate that over 3,000 corruption cases submitted to the CPEAC between 2004 and 2017 led to the pretrial custody of approximately only 800 suspects. At the same time, the country’s anti-corruption criminal policy (MinJus 2009) recommends systematic pretrial custody due to the high risk of suspects fleeing from justice. According to CPEAC data, the conviction rate in those cases that were tried was approximately only 39% (Comité de Pilotage 2014).

Therefore, in 2015 the national anti-corruption strategy called for the creation of completely stand-alone and independent anti-corruption courts, the Pôles Anti-Corruption (PACs). The need for such courts to fight impunity was one of the main recommendations arising from the public consultations that were conducted when developing the strategy. Consequently, the PAC law was adopted by parliament in 2016, and the first PAC of the capital city Antananarivo became operational in June 2018. Both the strategy and the law itself cite the CPEAC’s low conviction rate as the main justification for creating the PACs.

This process was mainly driven by BIANCO, whose Director General initiated the anti-corruption strategy. He was also the driving force behind the reform committee charged with implementation of the strategy and development of the PAC law. Frustrated by the lack of convictions, other anti-corruption institutions, such as the coordinating Comité pour la Sauvegarde de l’Intégrité (CSI), the financial investigation service (SAMIFIN), and civil society organisations and media, also supported the reform. The Ministry of Justice and the country’s judges were, in general, opposed and parliament adopted the PAC law only after receiving significant pressure from the government. That pressure, in turn, was the consequence of donor pressure – in particular relating to a specific conditionality in the European Union (EU) budget support programme.

Donor support proved essential: international donors funded the overall process, from the development of the anti-corruption strategy and PAC law to supplying the PAC’s office equipment and training judges and clerks. Conditionalities of both the EU budget support programme and the International Monetary Fund Extended Credit Facility provided to Madagascar included specific requirements to be met within the process, and helped overcome multiple attempts by the government to slow down reform. For instance, when necessary regulations were delayed or the government took months to nominate the preselected national PAC coordinator, these issues were included in donor conditionality matrices until the government capitulated. BIANCO and other anti-corruption bodies coordinated closely with donors to make use of this leverage in a politically astute approach to resolving this issue.

Institutional set-up: How the court works and its limitations

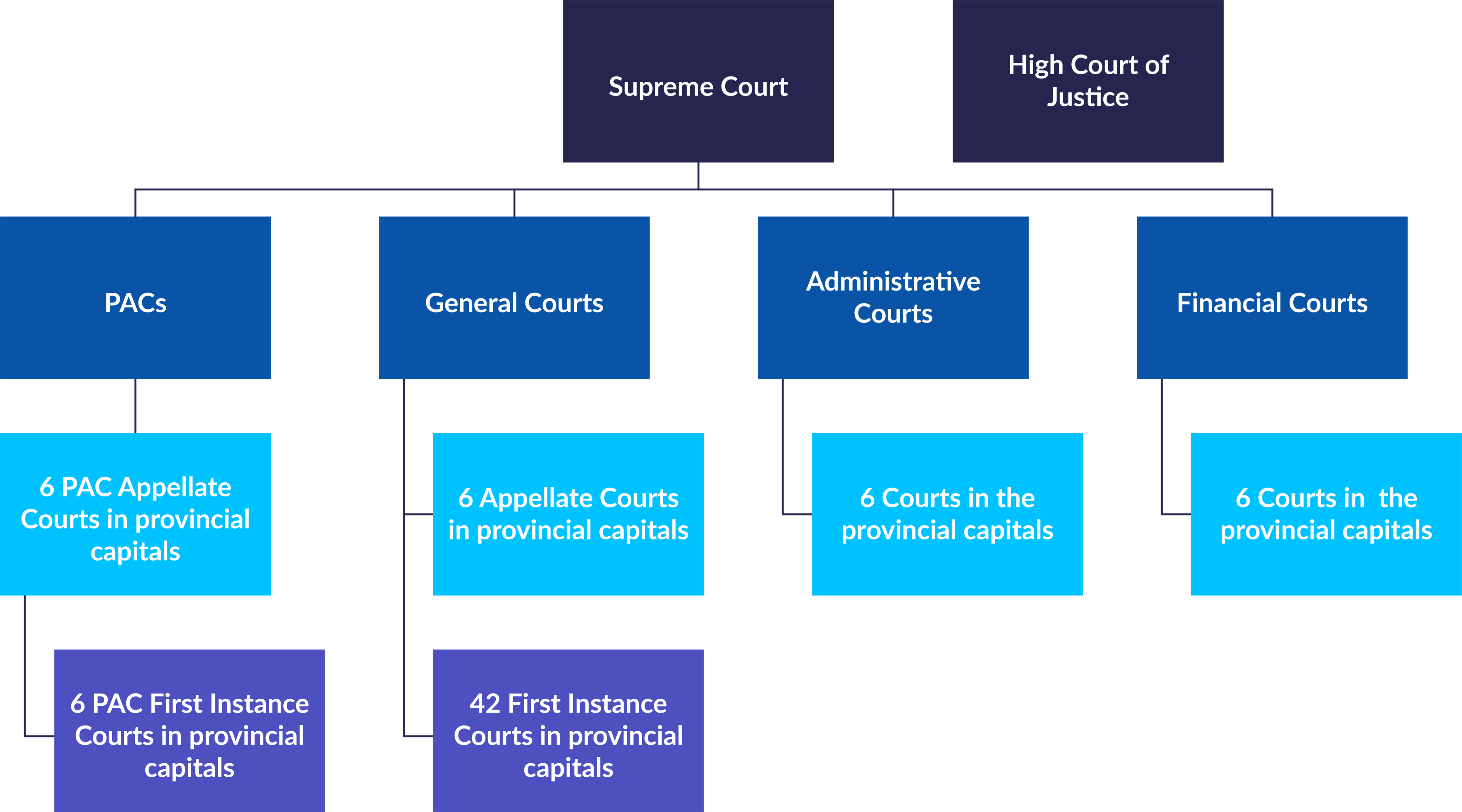

The PAC is a separate, stand-alone unit within the judicial hierarchy, consisting of both original/first instance and appellate courts and including a division for the seizure and confiscation of assets. The appellate decisions of the PAC are subject to appeal before the Supreme Court. Staffing of the first PAC of Antananarivo includes ten judges, eight public prosecutors,130a964d11d0 and 12 clerks. The national coordinator and administrative staff are not part of the jurisdiction but of the executive (Ministry of Justice) and have only a support function. It is intended that additional PACs will be established in the other five provincial capitals in the near future.

In principle, all corruption and money laundering offences fall within the exclusive jurisdiction of the PAC, as well as a wide range of other serious and/or complex economic and financial crimes. In late 2018, a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the PAC and the general court of Antananarivo assigned values and specified criteria relating to seriousness and complexity, in order to define more precisely the relative competencies of the two courts.

However, the PAC’s jurisdiction is limited by two other courts that were also set up in 2018. First, a donor-sponsored special court for crimes related to the illegal logging and trade of rosewood timber has an overlapping jurisdiction regarding cases that involve corruption. Second, in response to pressure by donors, the political opposition, violent protests, and eventually a decision by the Constitutional Court, the former government also established a High Court of Justice (Haute Cour de Justice) (HCJ). The president, members of government, and leaders of parliament and of the Constitutional Court can now only be tried before the HCJ for any offences related to the exercise of their duties. This undermines the exclusivity of the PAC regarding corruption and money laundering offences. The HCJ is part of the constitution of Madagascar of 2010 but was not established until 2018.

The PAC can hear cases brought by any institution or private person. In practice, most cases are transmitted to the PAC by law enforcement and anti-corruption authorities, with no special relationship between the PAC and BIANCO. The PAC law invites civil society organisations to report corruption but does not provide them with a specific role in the judicial process, despite such demands from activists during the law-making process. During the investigation phase, both BIANCO and other law enforcement agencies cooperate closely with the PAC’s prosecutors. Conventional law enforcement agencies such as the police can be ordered by the PAC prosecutors to do this, while BIANCO cooperates on a voluntary basis as an independent anti-corruption authority.

Figure 1: Position of the PACs in Madagascar’s judicial system

Note: The PAC only exists in Antananarivo to date, the other five provincial capitals will follow.

Measures to safeguard integrity and independence

To protect the integrity and independence of the PAC, a number of special design features were introduced. Neither these nor the overall structure of the PAC followed any particular models from other countries, but were developed by the reform committee charged with designing the law. More importantly, the law established the PAC Monitoring and Evaluation Committee (Comité de Suivi-Evaluation des PAC) and appointed its members from the heads of anti-corruption authorities, the Minister of Justice, and civil society representatives. This committee manages the selection, renewal, and lay-off of PAC members, deals with complaints against those members, and supervises the national coordinator. It makes decisions collegially and is designed to protect the PAC from interference from the executive and, in particular, the Ministry of Justice.

The committee has an essential role in the selection process of PAC judges and clerks. Following an open call for applications, background checks on candidates are conducted by BIANCO with the committee preselecting three candidates per position. The superior magistrate council (Conseil Supérieur de la Magistrature) can then nominate only judges and clerks from these shortlists; this limits its influence in the recruitment process, which often caused issues of integrity within the CPEAC. The process is similar for the national coordinator of the PAC in that the government, rather than the superior magistrate council, nominates the coordinator based on a shortlist of three candidates.

Once the PAC judges are recruited, they are given a fixed (renewable) mandate and cannot be removed unless the committee confirms serious misconduct has taken place. In ordinary jurisdictions, judges are occasionally threatened with deployment to very remote regions of Madagascar if they do not yield to influence from the Ministry of Justice and, for instance, liberate suspects that are close to government.

PAC members receive a specialisation allowance, which increases their income by approximately 1.5 to 2 times that of ordinary judges and clerks. As an institution, the PAC receives its own budget and is autonomous in its utilisation, further strengthening financial independence. Overall, these special features illustrate clearly that the main objective of creating the PAC was indeed to protect the integrity and independence of anti-corruption jurisdictions.

Evaluating performance and identifying issues

After less than a year in operation, it is too early to assess whether the PAC is indeed more effective than its predecessor. Initial data paint a moderately positive picture. The number of cases adjudicated by the PAC’s first instance court has been steadily increasing, from three in the first quarter of the PAC’s existence (DCN 2018) to 14 and 21 in the second and third quarters respectively. The same is true for the conviction rate, which increased from 36% to 39% and then to 67%. The low rates can be explained by the fact that the PAC has been trying the backlog inherited from the CPEAC first. According to observers, this backlog includes many cases from the CPEAC prosecutors with little chance of a successful conviction. These were already at the judgement phase when handed over to the PAC.822cb276aca2 Representatives from BIANCO and other anti-corruption institutions have praised the PAC for its performance so far, as well as its improved collaboration.

Observers and the media report that a number of grand corruption cases are currently being tried by the PAC, including influential businessmen and former Members of Parliament. However, in late 2018, the Constitutional Court obliged the PAC to transfer the grand corruption cases relating to former members of government to the new HCJ, which now has exclusive competency to try high-level politicians. Given that initiating a prosecution at the HCJ requires a majority in parliament, and that the HCJ comprises representatives of parliament and the executive, criminal proceedings against high-level politicians close to the regime in power have largely halted. Impunity of the powerful is therefore likely to persist, significantly undermining the initial hopes placed in the PAC. This is somewhat ironic given that the former government feared, and some donors hoped, that the HCJ would reduce impunity. However, Malagasy jurisprudence is clear that in the absence of the HCJ, the far less political and more objective PAC would have jurisdiction over high-level politicians.

Another unresolved challenge is in setting up the other PACs in the other five provincial capitals of the country. The first attempt at setting up a PAC in the port town Toamasina proved unsuccessful after the recruitment committee was not able to identify enough judges who not only met the strict criteria of expertise and integrity, but also were willing to take up this difficult job. Given this context, setting up five more PACs would also likely drain important human resources from the remaining judiciary. Therefore, the PAC Monitoring and Evaluation Committee is currently discussing whether to limit the number of PACs to three, or even just one national PAC. While cases are spread across the country, most grand corruption cases are tried in the capital, raising doubts about the effectiveness of decentralising the PAC. One could also argue that the difficulties in finding a sufficient number of qualified judges for Toamasina proves the rigorousness of the recruitment process.

Furthermore, funding remains a challenge – both in terms of setting up new PACs and rendering the PAC of Antananarivo more operational. The 2018 general budget of the government did not include any provisions for the PAC, and in the 2019 general budget the PAC’s allowance is included within that of the Ministry of Justice. This allows the ministry to exploit budgetary procedures to maintain a close grip on the actual availability of funds for the PAC, thus undermining its financial autonomy. Donors have been forthcoming to fill the budgetary gaps, but a more sustainable financing solution that protects the PAC’s independence has not yet been proposed.

Early success but challenges remain

The creation of Madagascar’s PAC is an insightful example of how champions of domestic reform (in this case the Director General of BIANCO) can leverage local partners and donor conditionality to push through changes against significant opposition from the rest of government. After ten years in existence, the performance of the national anti-corruption authority was tainted by low conviction rates in the courts, and BIANCO saw no alternative option other than to set up specialised and independent anti-corruption courts. To achieve this goal, BIANCO built coalitions with other anti-corruption institutions, civil society, and donors. However, it was the leveraging of specific indicators in donor conditionalities that proved most effective for BIANCO in overcoming reform barriers. Without those, observers agree that the PAC would not exist.

To protect the PAC from interference and safeguard its integrity and independence, Madagascar introduced a number of sui generis design features: a multi-institutional supervising committee (which comprises, among others, a civil society representative), a complex recruitment process of judges and clerks managed by the committee and featuring integrity background checks, fixed mandates of judges and clerks, better pay, and financial autonomy. While it is too early to provide a final verdict on their effectiveness, it appears that they have helped improve the PAC’s performance. However, the PAC experience also shows that such design features can often be undermined. For instance, while the recruitment process of the PAC national coordinator gives the government only a limited role, it was able to play for time and delay the nomination of one of the preselected candidates for several months. Similarly, the government has also been able to limit the PAC’s financial autonomy by exploiting budgetary procedures.

Finally, the creation of a parallel court for high-level politicians further undermines the PAC’s potential. The PAC has now lost its ability to end impunity for those who should be its biggest target. All these examples show that legal constraints such as the PAC’s special design features cannot fully replace a lack of political will. The PAC is likely to improve anti-corruption measures in Madagascar, but the quest for an end to impunity of the powerful will continue.

- This Brief is based on a review of documents and semi-structured interviews, in early 2019, with members of the PAC, BIANCO, civil society organisations, and legal experts in Madagascar.

- 61% of the PAC’s magistrates (judges and prosecutors) are female, compared to only 52% in the overall judiciary of Madagascar. Sources: Interviews with PAC and legal experts.

- Unfortunately data showing how the prosecution and judgement of new cases compares to cases inherited from the CPEAC does not exist.