Query

Please give an overview of the relationship between illicit financial flows (IFFs) and development in ASEAN member states.

Caveat

The scope of this Helpdesk Answer is wide, covering the topics of illicit financial flows (IFFs), their relationship to development outcomes, as well as how these topics manifest in up to ten Southeast Asian countries. Therefore, the literature review and treatment of these different topics should be understood as non-exhaustive in nature and more as an entry point. The reader is invited to consult the listed sources for more detail.

Furthermore, many of the sources relied on in this Helpdesk Answer derive from the mid-2010s. Some of their findings may not be up to date with current developments.

Introduction

According to Erskine and Eriksson (2018:1), there is now a ‘consensus that Illicit financial flows (IFFs) have wide-ranging adverse consequences for developing countries’ economic management, growth and development, making it a priority on the development agenda’.

Indeed, the concept of IFFs gained significant traction in multilateral circles in the mid-2010s. In 2015, a high-level panel under the auspices of the UN Economic Commission for Africa and of the Africa Union published a report (commonly known as the Mbeki report) which estimated that African countries lost over US$1 trillion in revenue due to IFFs in the preceding 50 years, approximately the same volume of official development assistance they received in the same timeframe (AU/UNECA 2015: 13). The report is widely considered to have triggered the inclusion of IFFs in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development framework in the form of Target 16.4 (Cobham 2018), which aims to:

‘By 2030 significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen recovery and return of stolen assets, and combat all forms of organized crime.’

While the number of academic studies and institutional initiatives on IFFs and development focusing on sub-Saharan Africa has remained strong, this is less so for other regions. For example, a coalition of civil society organisations based around the Asia-Pacific wrote a joint statement addressing the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) arguing that ‘Asia-Pacific countries are late to this conversation’ but also that there was ‘growing momentum on this front which needs to be consolidated’ (CBGA India 2019: 2).

This Helpdesk Answer surveys the evidence of IFFs and development in Southeast Asia (SEA), with a particular focus on the ASEAN member states. While SEA is widely considered to be one of the fastest developing regions in the world – according to the Asian Development Bank, the average GDP growth in mid-2023 was 4.6% (Rasjid 2023) – this has been accompanied by other trends such as the rapid expansion of transnational organised crime syndicates (Tanakasempipat 2025) that are indicative of enhanced IFF risks.

This answer first gives a background on the concept of IFFs, giving a high-level overview of the debates on how to define and measure them, before outlining several studies that have examined the relationship between IFFs and various development outcomes. It then concentrates on these topics within the ASEAN region and each of its ten member countries, drawing on the limited but growing body of evidence available. It concludes with a non-exhaustive mapping of bodies actively working on IFFs, development and related issues across SEA and the Asia-Pacific region more widely.

IFFs and development

According to Transparency International (n.d.)

‘Illicit financial flows [IFFs] describe the movement of money that is illegally acquired, transferred or spent across borders. The sources of the funds of these cross-border transfers come in three forms: corruption, such as bribery and theft by government officials; criminal activities, such as drug trading, human trafficking, illegal arms sales and more; and tax evasion and transfer mispricing.’

Furthermore, Transparency International (n.d.) holds that, given the large volume of IFFs, ‘[t]hey have a major impact on the global economy with a devastating impact on poorer countries and have clear links to corruption’.922dd06e2780

Aziani (2017) notes that while the concept of IFFs has been received enthusiastically in development circles, it has been confronted by two primary challenges. The first pertains to defining IFFs or classifying which kinds of activities and associated financial transactions should come under its purview. The second concerns measuring the scale of IFFs, which is inherently challenging given it concerns activities that offenders attempt to disguise.

Definition

Generally, IFF is used as an umbrella term, aggregating different illicit activities. Reuter (2017:1;3) points out that while aggregating in this way can be an effective advocacy tool, it is necessary to disaggregate these activities for the purposes of research, for example, to collect reliable data on IFFs and for exploring the ways in which IFFs can be regulated and controlled.

In the initial aftermath of the adoption of the 2015 Agenda, there were challenges in coming to a common understanding to define and disaggregate IFFs. While there was generally a consensus among policy actors and academics that activities (often termed predicate crimes) such as terrorism, tax evasion, corruption and illicit trade fall under the concept of IFFs (Brandt 2020: 21), there was political resistance from some countries on including legal forms of tax avoidance, such as profit shifting practices exploited by multinational companies (Cobham 2018).

Aziani (2017) argues this stems from disagreement about whether to adopt a law-based or normative approach to IFFs, whereby the latter would include activities which are detrimental to society, even if not legally prohibited. For example, Brandt (2020: 21) argues that given that the word illicit rather than illegal is used, activities not adhering to the spirit of the law should also be included as IFFs. Similarly, the International Tax Compact (ITC) argues on behalf of a wider approach from a development perspective because profit shifting practices causes major revenue loss for developing countries and a definition ‘based strictly on legality would fail to fully identify the financial resources that should be retained for those countries’ development’ (ITC 2023: 19).

Nevertheless, in recent years greater political alignment has been achieved. In 2020, UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), in their role as custodians of the SDG 16.4 target, developed their Conceptual Framework for the Statistical Measurement of IFFs, which puts forward a statistical definition of IFFs as ‘[f]inancial flows that are illicit in origin, transfer or use, that reflect an exchange of value and that cross country borders’. In 2022, the conceptual framework was endorsed by member states at the UN Statistical Commission (SDGPulse 2024).

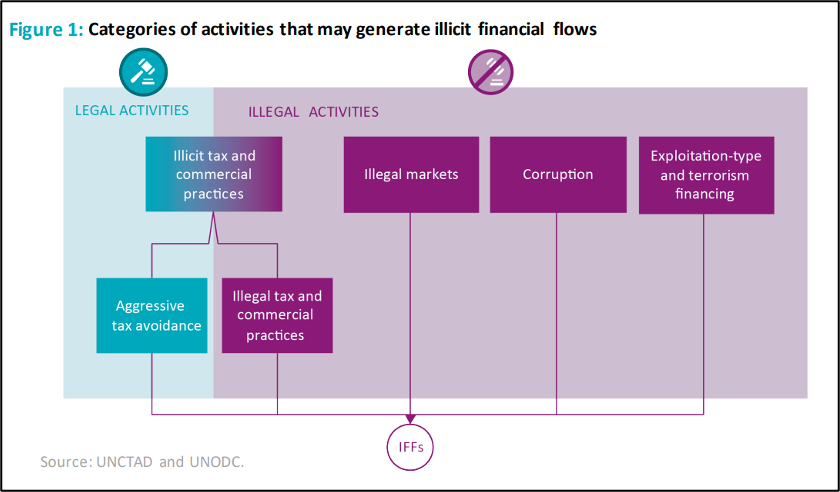

This definition is supported by a categorisation of activities that may generate IFFs (see Figure 1). Notably, this considers a mix of illegal and legal activities, and under the latter, ‘aggressive tax avoidance’ which can overlap with the ‘profit shifting of multinational enterprise groups’ (UNCTAD and UNODC 2020: 15).

Figure 1: UNCTAD and UNODC (2020)’s categorisation of activities that may generate IFFs

Source: (UNCTAD and UNODC 2020: 13)

Other core elements of the definition include that IFFs ought to constitute an exchange of value (as opposed to purely financial transfers), relate to a flow over a given time (as opposed to stock values) and involve a transfer across borders (as opposed to movements occurring within a domestic jurisdictions) (UNCTAD and UNODC 2020: 13).

Furthermore, IFFs cover both inflows and outflows related to illicit income generation and management (UNCTAD and UNODC 2020: 19). When IFFs flow out of a country, the term origin jurisdiction is often applied; conversely, IFFs flow into a destination jurisdiction or pass through a transit jurisdiction (IMF 2023). However, these should not be viewed as static, and in many cases IFFs are routed through transit and destination jurisdictions with the aim of eventually returning to the origin jurisdiction in a process known as round tripping’ (Kar and Freitas 2013: 4).

Due to their clandestine nature and the lack of comprehensive and clear data, measuring IFFs is inherently challenging (Duri and Rahman 2020), and there are risks that the volume of flows is underestimated. Conversely, as a concept aggregating different activities, available information on IFFs is often divided across a range of institutions at the national level and there can be a risk of double counting (ITC 2023: 20).

Nevertheless, experts have made attempts to measure IFFs, which are commonly divided into top-down and bottom-up approaches (Aziani 2017; IMF 2023).

Top-down approaches typically attempt to indirectly estimate the volume of IFFs by relying on proxy datasets, such as the level of capital flight from a country, discrepancies in imports and export statistics, net errors and omissions in balance of payment statistics and the calculation of the stock of undeclared wealth in offshore jurisdictions, among others (Aziani 2017; IMF 2023; Brandt 2020: 21).

Top-down approaches initially gained more traction given they rely on publicly available data and are amenable to comparisons across countries and regions. For example, Global Financial Integrity (GFI) used international trade data from the IMF to identify ‘value gaps’d6bf798a62c6 in imports and export as a measure of IFFs, with the most recent dataset from 2021 analysing the trade of 148 developing countries with 36 advanced economies (see Figure 2) (GFI 2021).

Figure 2: Global Financial Integrity’s estimate of trade-based value gaps

|

|

Region |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

Average |

|

1 |

Developing Asia |

290.2 |

361.2 |

422.5 |

386.2 |

407.4 |

391.9 |

387.4 |

373.4 |

396.5 |

469.1 |

388.6 |

|

2 |

Developing Europe |

114.6 |

137.9 |

165.5 |

158.9 |

170.9 |

172.7 |

148.7 |

151.9 |

171.4 |

193.6 |

158.6 |

|

3 |

Western Hemisphere |

84.5 |

104.6 |

123.3 |

120.8 |

122.7 |

88.6 |

80.5 |

74.3 |

86.0 |

88.6 |

97.4 |

|

4 |

Middle East & North Africa |

39.1 |

54.2 |

52.8 |

58.2 |

66.7 |

68.8 |

62.8 |

60.0 |

64.4 |

59.3 |

58.6 |

|

5 |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

22.9 |

21.9 |

29.0 |

28.3 |

27.5 |

25.9 |

23.1 |

22.6 |

26.2 |

24.4 |

25.2 |

Total Value Gaps Identified in Trade Between 134 Developing Countries and 36 Advanced Economies, 2009-2018, by Developing Country Region, in USD Billions Source: GFI 2021: 10

In a report for ESCAP, Kravchenko (2018: iii) applied a similar approach, focusing on bilateral export and import data from 2016 and concluded there was ‘evidence of substantial illicit financials inflows and outflows within the Asia-Pacific’, with significant development impacts (estimating up to 7.6% of tax revenue in the region may have been lost in 2016 due to trade misinvoicing).

Nevertheless, top-down approaches have also been criticised on several grounds. For example, Brandt (2020) argues that balance of payments data may capture licit as well as illicit flows. Duri and Rahman (2020) point out that while the datasets used in such approaches may be effective in estimating some forms of IFFs – for example, trade-based illicit financial flows – they are more limited in doing so for IFFs originating from corruption and other criminal activities. Indeed, GFI (2021) has now clarified that its approach only serves to measure IFFs related to trade misinvoicing.

Conversely, bottom-up approaches typically do not strive to measure all forms of IFFs in one effort but instead focus on measuring the volume of proceeds from relevant illicit activities and aggregates these values to arrive at overall estimates (IMF 2023). This includes, for example, the so-called Walker Gravity model which involves estimating the proceeds of predicate offences and assessing the direction of their overseas movements (Aziani 2017).

Flentø and Simao (2022: 3) argue in favour of such an approach, stating ‘[o]nly by applying much more sector-specific and granular analysis can we hope to develop policy tools that can effectively assess what kinds of crime hamper development and deal with the underlying crimes of IFFs’. Similarly, SDG16Now (n.d.) puts forward that a more reliable indicator of IFFs would give policymakers a clearer idea of the financing for development needs of countries affected by IFFs.

Bottom-up approaches may be more work-intensive and require coordination among the national authorities who hold the micro-data for flows originating from different predicate crimes; the IMF (2023) notes therefore that such efforts must be matched by political will and underpinned by national strategies.

The 2030 Agenda includes indicator 16.4.1 (total value of inward and outward illicit financial flows, in current US dollars) on the basis of which progress towards the achievement Target 16.4 can be measured. As co-custodians of the indicator, UNODC and UNCTAD have promoted what can be characterised as a bottom-up approach in the aforementioned conceptual framework, that aims to generate data for 16.4.1 but with disaggregated measures of IFFs for different kinds of predicate crimes.

Between 2020 and 2022, a project led by a consortium of UN agencies titled Statistics And Data for Measuring Illicit Financial Flows in the Asia-Pacific Region was implemented in six pilot countries, with a view to testing and operationalising the methodology and gathering of national-level data for 16.4.1. Nevertheless, UNESCAP (2024: 9) conceded that, as of 2024, the vast majority of countries in the Asia-Pacific region (56) lacked any useable data for indicator 16.4.1, and called for greater investment to expand data availability, accuracy and disaggregation in the region.

The relationship between IFFs and development

Aziani (2017) holds that ‘acknowledging that IFFs can have detrimental effects on economic growth and poverty alleviation has become a mainstream position in development economics’. Bak and Jenkins (2025) explain that these effects tend to be cumulative and worsen over time.

One of the most self-evident impacts of IFFs is on domestic revenue mobilisation. Illicit outflows from an origin jurisdiction reduces the revenue available to address development needs and furthers dependency on aid (IMF 2023; World Bank 2016: 1). Similarly, SDG16Now (n.d.) argues that clear links can be drawn between Target 16.4 and Target 17.1 which calls on governments to ‘strengthen domestic resource mobilisation, including through international support to developing countries, to improve domestic capacity for tax and other revenue collection’, therefore suggesting IFFs act to the detriment of financing for development. SDG16Now (n.d.) note the potential of countries locating and returning stolen assets lost from illicit financial flows (IFFs) and using them to fund development projects.

According to the IMF (2023), resource rich and low-income fragile and conflict-affected states are often most heavily affected by IFFs. In these countries, IFFs exacerbate domestic corruption and governance challenges and preclude the use of the potential revenues resulting from the extractive sector to support the development priorities of their country. Similarly, Cobham (2018) argues that losses incurred from IFFs are most intensely felt in lower-income countries that already typically have lower per capita spending on crucial public services such as education and health. In this way, IFFs can also exacerbate inequality by creating disproportionately detrimental impacts on those citizens already most ‘left-behind’ (Bak 2020). Lain et al. (2017:7) point out that ‘fewer funds for government-provided services as a result of illicit financial outflows can also have a knock-on effect in terms of increasing a government’s inclination to borrow to fill in the gaps, thus increasing indebtedness’.

The IMF (2023) outlines other negative macro-economic consequences of IFFs, including the distortion of market prices and inhibition of genuine investment. Similarly, Bak and Jenkins (2025) explain that IFFs are associated with a reduction in private capital accumulation and investment in an affected jurisdiction. In this vein, IFFs associated with illicit trade discourage fair competition and distort an equal playing field for other companies, thus discouraging investment (TRACIT 2019: 3). Furthermore, in terms of tax evasion and avoidance, Brandt (2020) points out that if people perceive others are evading taxes, they in turn are more likely to avoid complying, thus aggravating tax losses.

Ortega and Sanjuán (2022) conducted an econometric analysis of the relationship between FDI and illicit financial outflows, estimated on the basis of GFI’s trade misinvocing data for 49 countries spanning the period 2008 to 2017. Among the finding,s, they identified a positive association between FDI outflows and trade-related IFFs in low-income countries (Ortega and Sanjuán 2022:208). Utilising a different approach, Ofoeda et al. (2022) found that the higher levels of anti-money laundering regulations (which may address many aspects of IFFs) tend not only to lead to higher levels of FDI, but also to accelerate FDI’s growth-enhancing impact of FDI in a country.

Herkenrath (2014) cautions against assuming ‘there is a one-to-one relationship between IFFs and investment losses’ in every case, given that IFFs might indirectly lead to the accumulation of capital if, for example, the activities lead to an increase in remittances from migrants. The IMF (2023) emphasises that even if destination jurisdictions can enjoy some short and medium-term economic benefits, they can also be negatively affected by the IFFs integrated into their economy in the long run. For example, their banking and real estate sectors can incur reputational risks but even face asset bubbles and busts (IMF 2023).

Several empirical studies have attempted to assess the relationship between estimated levels of IFFs and development outcomes, although these may be limited by the definitional and measurement-related challenges outlined above.5586ef5cb74e For example, Spanjers and Foss (2015: iii) examined correlations between IFF levels estimated by GFI by using their aforementioned methodology and countries’ scores on the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Human Development Index. They concluded that, for countries where IFF levels are high, the development score tended to be lower, and hypothesised that this negative relationship could be explained in part by the loss of domestic revenue incurred through trade misinvoicing. In another study that assessed the risk levels of IFFs in a jurisdiction based on the evaluations made by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), it was found that tax revenue loss was higher in countries with associated with IFFs (Combes et al. 2021)

Beyond the macro-economic effects, the literature suggests that IFFs have other impacts that still severely undermine sustainable development. These are often linked to the wider societal harms wreaked by predicate crimes; because IFFs act as a vehicle for laundering and safeguarding the proceeds of such crimes, they can therefore drive these illicit activities and the harms they engender.

These pathways are manifest in many areas of development. For example, IFFs tied to corruption encourage private capture of state budgets, which in turn can lead to the misallocation of public expenditure for development needs (Cobham 2018; IMF 2023). IFFs tied to environmental crimes can contribute to the degradation of natural resources and even exacerbate climate change (IMF 2023; Jenkins 2024: 2). In fragile and conflict-affected states, armed and terrorist groups may engage in predicate crimes and rely on IFFs as a source of revenue to sustain their operations, resulting in heightened insecurity (Jenkins 2024: 2). IFFs originating from some predicate crimes, such as sex trafficking, have significant gendered impacts and disproportionally affect women (Merkle 2019).

More generally, the growth of illicit economies can lead to a loss of state legitimacy and undermine levels of trust in public institutions and rule of law (IMF 2023; Cobham 2018). Reuter (2017:2) adds that if economic and political elites are able to shift their wealth to other jurisdictions, they are less likely to push for domestic law reforms that would protect their property rights.

IFFs and development in Southeast Asia

Regional overview

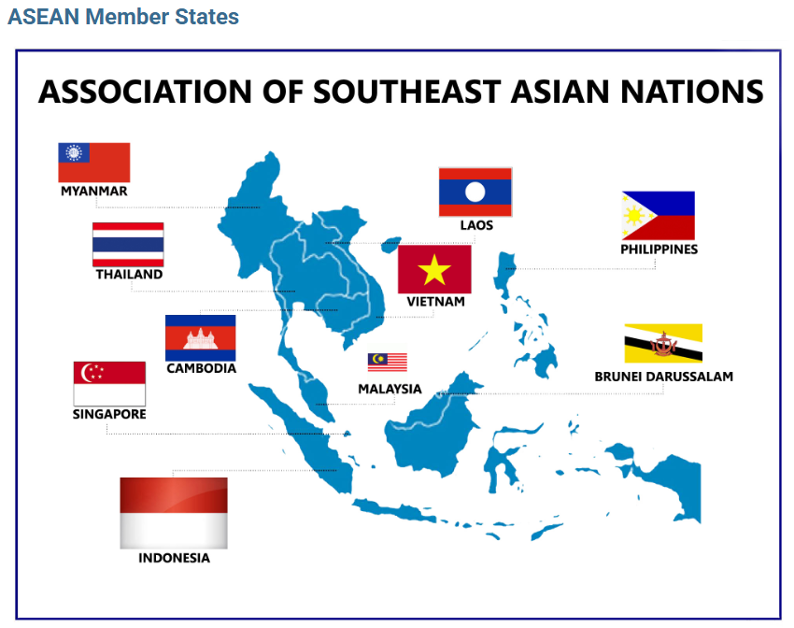

This section of the Helpdesk Answer builds on the previous section and focuses on the available evidence of IFFs and development in Southeast Asia (SEA), with a particular focus on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). It must be emphasised that, as a regional organisation whose membership is subject to an accession process and criteria, ASEAN is not synonymous with the SEA region. Depending on the source, several other countries which are not ASEAN member states may be considered as part of SEA. However, for matters of coherence and scope, this part of the Helpdesk Answer concentrates on the ASEAN region, specifically the current ten ASEAN member states:8c366c0979b9

- Brunei Darsallam

- Cambodia

- Indonesia

- Lao People's Democratic Republic (PDR)7ba2c36f8ac3

- Malaysia

- Myanmar

- Philippines

- Singapore

- Thailand

- Vietnam

Figure 3: Map of ASEAN member states as of April 2025

Source: Kingdom of Cambodia, Ministry of Foreign Affairs & International Cooperation

The ASEAN was established in 1967 and constitutes a regional grouping that aims to promote economic and security cooperation among its members (Council of Foreign Relations 2025). In recent decades, the region has been noted for its dynamic economic growth and is increasingly an attractive destination for foreign direct investment (Schoeberlein 2020: 2).

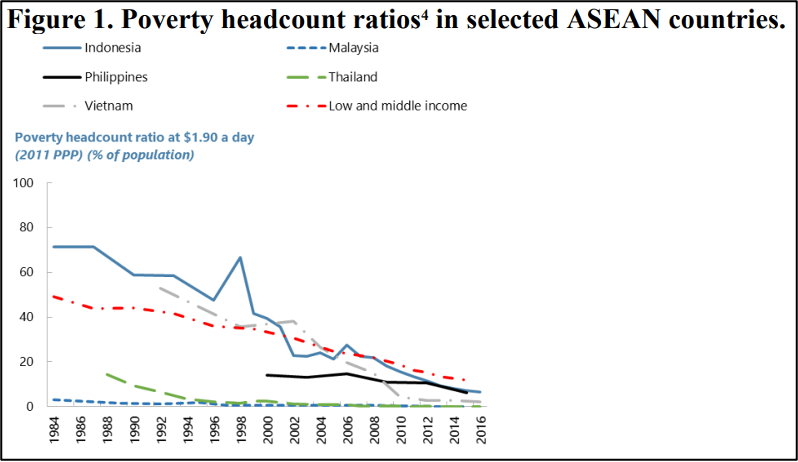

Alekhina and Ganelli (2020: 4) noted that, in recent decades, average GDP growth across ASEAN member countries has steadily increased and surpassed the world’s average growth, leading to decreased poverty levels (see Figure 4), but this has failed to lead to a more equal income distribution. For example, the World Inequality Database (2023) found that income inequality levels in Thailand are among the highest in the world, with the richest 10% of the population earning more than half of the total national income.

Figure 4: Alekhina and Ganelli’s (2020) tracking of poverty headcount ratios in select ASEAN countries (1984-2016)

Source: Alekhina and Ganelli 2020: 7

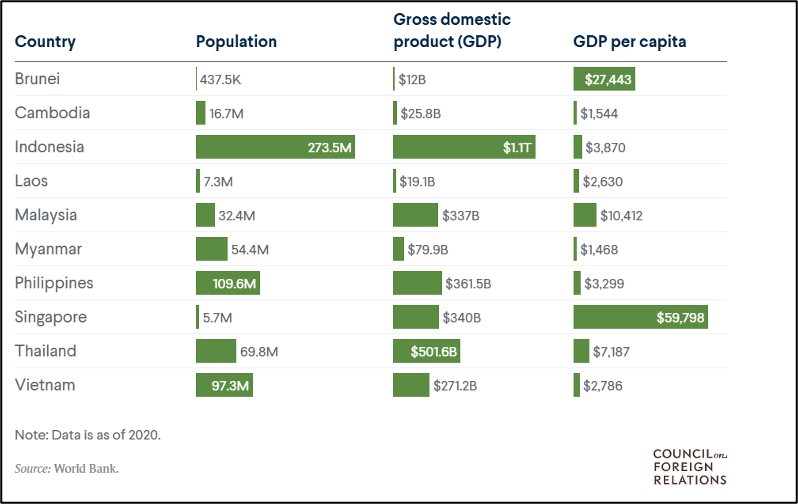

In 1987, when the World Bank began classifying countries by income status, it determined that among the current ASEAN members, there were five lower-income countries (Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Vietnam), three lower middle-income (Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand) and two high-income countries (Brunei, Singapore). By 2024, this had changed to five lower middle-income (Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Philippines, Vietnam), three upper middle-income (Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand) and two high-income countries (Brunei Darsallam, Singapore) (World Bank 2024). Nevertheless, there is still a wide divergence in levels of economic development across the ASEAN members (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Comparative economic development indicators of ASEAN countries (2020)

Source: Council of Foreign Relations 2025

The rapid economic development has been driven in part by the regional economic integration efforts of ASEAN, which include goals to incrementally create a single market and increasing intra-ASEAN trade and investment (Council of Foreign Relations 2025). Furthermore, the ASEAN has concluded trade agreements with other countries, most notably the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which paired ASEAN members with Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea to form the world’s largest trading bloc (Council of Foreign Relations 2025).

The concept of IFFs does not appear to be directly addressed in ASEAN’s policy and legal framework. In 2016, UNODC warned that, while fostering development, economic integration in Southeast Asia, including in the ASEAN region, was helping trigger new security challenges, including the expansion of organised crime (UNODC 2016: i). Relatedly, it found ASEAN’s institutional agenda for countering transnational crime was inadequate to counter threats associated with integration (UNODC 2016: 1). In an interview, Jeremey Douglas, the regional representative of the UNODC for Southeast Asia and the Pacific, reportedly said some key ASEAN member states had begun prioritising action on border management and scanning illicit flows, but that political interest had not yet translated into practical change (The Economist Intelligence Unit 2018: 5).

The ASEAN’s current economic integration and development plan is set out in the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2025, which was adopted in 2015 with goals to be achieved in 2025 (ASEAN Secretariat n.d.). The blueprint does not mention IFFs, but the related Political-Security Community Blueprint 2025 does contain certain commitments related to IFFs, such as:

- ‘Enhance and encourage cooperation among financial intelligence/authorised units of ASEAN Member States in the areas of collection, analysis and dissemination of information regarding potential money laundering’ (ASEAN Secretariat 2016: 7)

- ‘Implement effectively the Work Programme of the ASEAN Plan of Action to Combat Transnational Crimes covering terrorism, illicit drug trafficking, trafficking in persons, arms smuggling, sea piracy, money laundering, international economic crimes and cybercrimes’ (ASEAN Secretariat 2016: 16)

Nevertheless, the literature suggests that significant vulnerabilities to IFFs across ASEAN member countries remain, which prevents the region from fully reaping the development potential associated with its economic growth. While each of ASEAN member country faces its own unique set of IFF risks (described in further detail below), there are also significant regional-level trends at play.

IFFs in the region are linked to a wide range of predicate crimes, including but not limited to: illicit wildlife trade (Amerhauser 2023: 16); illicit trade in counterfeit medicines (Amerhauser 2023: 18); terrorist financing (Devi 2024); narcotics trafficking (Herbert 2020); illegal fishing (APG 2023b); illegal logging (UNODC 2016: 24); corruption (Schoeberlein 2020); human trafficking and cyber-enabled fraud (Magramo 2024).

These are often facilitated through regionally active criminal actors and marketplaces which have experienced a recent spike. According to UNODC (2025: 3), ‘crime syndicates in Southeast Asia have emerged as definitive market leaders in cyber-enabled fraud, money laundering, and underground banking globally, actively enhancing collaboration with other major criminal networks around the world’. Since the de facto authority in Afghanistan imposed a ban on opium production in 2022, production has increased dramatically in SEA, primarily in Myanmar (UNODC 2023d: iii). Within the ASEAN region, there are different hotspots for IFFs. Amerhauser (2023: 12-13) describes how the shadow economy in the Golden Triangle – the border area between Lao PDR, Myanmar and Thailand – is estimated to generate billions of US dollars annually. Furthermore, the substantial cash-based, informal sectors in the Mekong region countries (encompassing Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam) can be vulnerable to cash smuggling and other forms of money laundering (Amerhauser 2023: 6; 18).

In many SEA countries, gaps in policy and legal frameworks enable IFFs. The Economist Intelligence Unit (2018: 15) notes that the law enforcement capacities against illicit trade and IFF vary widely across the various ASEAN countries; those countries with a lower GDP – namely, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar – often struggle to close the technological, policy and human capacity gaps they face.

UNODC (2024c:15) notes that while special economic zones (SEZs) have been established across Southeast Asia with the intention of supporting economic development (for example, by attracting foreign investment through lower tax rates), they have inadvertently enabled various criminal activities and ‘industrial-scale money laundering’. The level of oversight of these zones is often low, which raises the possibility that illicit flows are comingled with legitimate flows (Amerhauser 2023: 5). The APG (2024a: 29) states that there is generally little information available on the beneficial ownership of legal persons in the wider Asia/Pacific region; UNODC (2024b) concludes there have been recent albeit nascent efforts to improve this across the ASEAN region. However, UNODC (2024c: 4) also flags the generally weak levels of oversight of the enabler professions for money laundering in SEA. In this regard, it highlights the rapid increase of the number of casinos and related businesses which evidence suggests are exploited to launder criminal proceeds into the formal financial system (UNODC 2024c:1).

Furthermore, UNDP has noted the prevalence of corruption across the ASEAN region and business leaders’ recognition of the need for enhanced anti-corruption to attract foreign investment (UNDP 2020: 11). Amerhauser (2023: 13) also describes how the increased levels of Chinese investment have ‘been linked to the proliferation of counterfeit goods and other illicit commodities, connecting criminal actors and making formerly isolated regions vulnerable to criminal exploitation trade-based money laundering’.

Evidence suggests that corruption is not only a source of IFFs in the region it is own right, but also an enabler of other illicit activitiescc64dfa4901b. In their study of Indonesia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Myanmar, East Timor and the Philippines, Baker and Milne (2015) allude to the common complicity of state actors and that there is often a ‘symbiotic relationship between Southeast Asian states and illicit practices and economies’. Schoeberlein (2020: 3) highlights several common governance challenges faced in the ASEAN region including a weakening rule of law, inadequate checks and balances, low levels of accountability and government transparency, overconcentration of bureaucratic power in the hands of (political) elites and ineffective regulatory environments and administrations. In a 2017 survey, 2,322 respondents from ten ASEAN countries were asked to rank 21 issues facing the region; corruption was chosen as most pressing problem, over other issues such as income disparity and social inequality (ERIA 2017: 21).

IFFs may exacerbate already low levels of domestic revenue mobilisation in the region. The Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering (APG 2024a: 29) found that, for the wider Asia-Pacific region and with the exception of Japan and South Korea, most Asian countries have ‘extremely low tax-GDP ratios’, and the regional average of 18% was lower than the equivalent figures for other regions of the world (Biyani 2020:2). Sisouphanthong et al. (2024) describes how the ASEAN region’s rapid economic growth and increasingly strong international trade portfolio threaten to be undermined by an accompanying increase in trade-related IFFs, which account for substantial tax revenue losses. They call on the ASEAN to step up efforts to prevent tax base erosion so its members can use the revenue towards socio-economic development and poverty reduction programmes (Sisouphanthong et al. 2024).

Similarly, UNODC (2016: 3) describes various development consequences linked to the proliferation of IFFs in SEA, including the distortion of the regional economy which ‘hurts the broader community of people and businesses that adhere to the rules and regulations’. Amerhauser (2023: 5) explains that countries in the Mekong region lose significant amounts of illicit proceeds to offshore tax havens, which deprives states of health, education and infrastructure and deepens inequality.

Wider, multidimensional development effects are also clearly present in the region. For example, TRACIT (2023: 2) explains how the prevalence of illicit trade in goods such as tobacco, petroleum, alcohol and pharmaceuticals leads to reduced tax revenues for governments and thus hinders ‘the ability of governments to invest in vital services such as education, healthcare and infrastructure’. However, given that organised criminal groups typically profit from such trade, TRACIT (2023: 2) also argue it undermines the political stability and security of the region, as well as fosters exploitative working conditions and leads to a greater circulation of counterfeit goods posing health and safety risks. Furthermore, they describe that illegal trade in natural resources, such as wildlife, timber and minerals, not only leads to significant revenue losses but also undermines the heritage and environmental sustainability of the region. Similarly, Osorio (2024: 55) describes how illicit wildlife trade also undermines the potential income of the eco-tourism sector in ASEAN.

When FATF identifies anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) gaps in its review process, it may place a country on the so-called black or grey lists which identify high-risk jurisdictions subject to a call for action and put jurisdictions under increased monitoring, respectively. This is typically followed by an action plan in which FATF sets out necessary policy reforms to secure delisting. Evidence suggests that the existence AML/CFT gaps and subsequent grey listing also undermines development and economic growth with one study finding that grey listing results in a ‘large and statistically significant’ reduction in capital inflows including foreign direct investment and bank inflows (Kida and Paetzold 2021). The continuing AML/CFT risks and inadequate controls has led to FATF grey-listing or blacklisting several ASEAN countries. Myanmar is currently blacklisted, Lao PDR and Vietnam are currently grey listed, while the Philippines and Cambodia have recently been removed from the grey list.

ASEAN country profiles

As with other regions, national-level data on IFFs is very limited. Myanmar and Vietnam are the only ASEAN countries to have collected data for part of indicator 16.4.1. by using the UNCTAD/UNODC methodology (UNODC 2023b). As explained above, this lack of data makes it difficult to quantify the losses and development impacts of IFFs.

Nevertheless, there is a growing body of literature and institutional reports which, even if they do not directly refer to IFFs, give some degree of insight into the predicate crimes and money laundering risks each ASEAN country faces. While it is not always clear the extent to which the proceeds of these crimes cross borders, the frequent involvement of transnational actors can be indicative of IFF risks. The implications for development outcomes are often underexplored in the literature although there are exceptions.

In this section, some examples of these findings are shared for each ASEAN country. These overviews should be understood as illustrative and non-exhaustive in nature. Indeed, in some ASEAN countries several major predicate crimes occur to serious levels. The reader is invited to consult the sources mentioned for more detail.

These overviews are also accompanied by a table of indicators covering various aspects of IFFs and development for each country. Nevertheless, these indicators are also non-exhaustive, cannot in themselves give an accurate overview of IFFs or attest to a relationship between IFFs and development outcomes. Furthermore, the indicators presented are not analysed in detail for every country and, again, the reader is invited to consult the sources for more information. Basic descriptions for each of these indicators is given in the table below.

Indicators covering various aspects of IFFs and development

|

Indicator |

Description |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

The World Bank assigns national economies to four income groups: low, lower middle, upper middle, and high, based on gross national income per capita measured in United States dollars. The source for the figures cited is (World Bank 2024). |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

Gross domestic capital per capita, purchasing power parity has been defined as ‘GDP divided by the midyear population, where GDP is the total value of goods and services for final use produced by resident producers in an economy, regardless of the allocation to domestic and foreign claims’. Accordingly, it is a macro-economic indicator used to compare the average standard of living of the populations of various countries. The source for the figures cited is World Bank (n.d.). |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

UNDP describes its Human Development Index (HDI) is ‘a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, being knowledgeable and having a decent standard of living’, contrasting from development indicators based solely on economic factors. Values on the index range between 0 (low development) and 1 (high development). The latest data derives from 2022. The source for the figures cited is UNDP (n.d.) |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

FATF (n.d.) describes its recommendations as ‘a comprehensive framework of measures to help countries tackle illicit financial flows’ and uses this to assess states’ capacities on AML/CFT. For each of the 40 recommendations, reviewed states are given one of the following ratings: compliant (C), largely compliant (LC), partially compliant (PC), not compliant (NC) (FATF 2024: 16). Furthermore, FATF’s framework sets out 11 immediate outcomes ‘that an effective framework to protect the financial system from abuse should achieve’ (FATF n.d.). For each immediate outcome there are four possible ratings: high, substantial, moderate or low levels of effectiveness (FATF 2024: 25). For purposes of this paper, only the number of recommendations and immediate outcomes by rating is given as an indicator. For detailed information on information on which recommendations and immediate outcomes received which rating, the reader is invited consult the relevant cited FATF reports. The source for the ratings cited are contained in the most recent Mutual Evaluation Report or Follow-up Report for each country as of late April 2025. |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

In its Global Organized Crime Index, GI-TOC calculates the criminality scores as an average of the criminal markets and criminal actors. These, in turn, are based on experts’ assessments of various risk factors (GI-TOC 2024:42). For criminal markets, these are: human trafficking; human smuggling; extortion and protection racketeering; arms smuggling; trafficking trade in counterfeit goods; illicit trade in excisable goods; flora crimes; fauna crimes; non-renewable resource crimes; heroin trade; cocaine trade cannabis trade; synthetic drug trade; cyber-dependent crimes; and financial crimes. The criminal actors are mafia-style groups, criminal networks, embedded actors, foreign actors and private sector actors. It uses a 0–10 system, where 10 indicates the highest criminality level. The source for the scores cited is GI-TOC (2024). |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

The CPI ranks 180 countries and territories worldwide by their perceived levels of public sector corruption. The results are given on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean). The source for the scores cited is Transparency International (2025b). |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

The Basel AML Index is a composite indicator based on 17 publicly available sources that measure money laundering and related financial crime risks around the world. It uses a 0–10 system, where 10 indicates the highest risk level (Basel AML Index 2024: 11). The source for the scores cited is Basel AML Index (2024) |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

Global Financial Integrity (GFI) uses ‘international trade data officially reported by governments to the United Nations in order to estimate the magnitude of trade misinvoicing activity’ in the form of value gaps between what any two countries had reported regarding their trade with each other, noting that this method ‘does not address all forms of IFFs’ (GFI 2021: 1). Its most recent estimates derive from the analysis of data available from the period 2009-2018 for 134 developing countries and 36 advanced economies. GFI frames results in several ways, including representing value gaps as a percent of total trade. The source for the scores cited is GFI (2021). |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific (2016) |

In a 2018 paper for the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, Kravchenko (2018) compared bilateral import and export data collected by UN Comtrade and the Centre d'Études Prospectives et d'Informations Internationales (CEPII) in 2016 to determine levels of trade misinvoicing by creating estimates of trade-based illicit inflows and illicit outflows affecting countries in the Asia-Pacific region (Kravchenko 2018: 8). The source for the figures cited is Kravchenko (2018). |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

The Tax Justice Network’s (TJN) State of Tax Justice Reports estimates the volume of tax revenue losses that arise from wealth hidden in secrecy jurisdictions, including by representing this as a percentage of GDP, which illustrates the extent of the fiscal losses a country experiences. TJN’s methodology relies on various assumptions and multiple steps to overcome data limitations and is described in more detail on pages 40-46 of the report (TJN 2024). The source for the figures cited is TJN (2024.) |

Brunei Darsallam

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

High income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

85,267.6 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.823 out of 1 Ranking: 55 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Recommendations

Immediate Outcomes

|

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 2.85/10 Ranking: 180 of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

N/A |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 4.3 Ranking: 132 of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

15.4% |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

N/A |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

5.9% |

Along with Singapore, Brunei Darsallam is one of only two high-income countries in the ASEAN region. The indicators suggest Brunei Darsallam faces low rates of criminality and generally low ML vulnerabilities, but the estimatedoffshore wealth owned by its citizens is a comparatively high at 5.9% of GDP.

According to the APG’s mutual evaluation report (MER), BruneiDarsallam faces relatively low domestic and transnational crime risks, but its ‘geographic proximity to higher ML/TF risk jurisdictions in the ASEAN region exposes it to foreign illicit financial flows which in turn creates internal ML/TF vulnerabilities and risks’ (APG 2023d: 6). Nevertheless, as BruneiDarsallam is not a regional financial centre, the APG determined its ‘risks of being used as a destination or transit location for criminal proceeds appear relatively low’ (APG 2023d: 6).

Nevertheless, other sources point to vulnerabilities to criminal activities. For example, GI-TOC (2023a) reports the frequent illicit trade of excise goods, as well as illegal timber harvesting in collusion with organised criminal groups from Myanmar and Malaysia. Furthermore, GI-TOC (2023a) reports financial crime risks, citing a case of a fraudulent Malaysian investment scheme linked to a BruneiDarsallam sovereign wealth fund. Indeed, in BruneiDarsallam, there have been high-profile corruption cases tied to IFFs; for example, former judges were accused of embezzling US$15.75 million from the high court’s bankruptcy office and laundering it abroad, including to UK-based accounts (Bandial 2020).

The full scope of predicate crimes and IFFs in Brunei Darsallam is obscured by the lack of media transparency in the country. In 2024, Freedom House (2024) ranked Brunei Darsallam as ‘not free’ in terms of people's access to political rights and civil liberties. Furthermore, GI-TOC (2023a) alludes to the prevalence of information gaps on many crimes in Brunei Darsallam, and noted – despite significant progress in some AML measures – Brunei Darsallam was behind on certain financial transparency measures, including a lack of beneficial ownership and tax transparency.

Cambodia

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

Lower middle income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

7,425.5 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.600 out of 1 Ranking: 148 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Recommendations

(APG 2023e) Immediate Outcomes

(APG 2023e) |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 6.85/10 Ranking: 20 of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

Score: 21/100 Ranking: 158 of 180 countries |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 6.75 Ranking: 21 of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

19.1% |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

Inflows: 1147 Outflows: 1681 Net outflows: 533 |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

1.5% |

According to the indicators, Cambodia has one of the lowest GDP per capita (PPP) rates and HDI scores in the ASEAN region, as well as high rates of criminality, money laundering risks and perceived corruption.

The APG’s most recent MER of Cambodia dates from 2017. It found that Cambodia’s geographical position and porous borders increased its vulnerabilities to money laundering, highlighting threats emerging from fraud/scams, corruption and bribery, drug trafficking, human trafficking, illegal logging, wildlife crime and goods and cash smuggling, and highlighted concerns with the AML/CTF capacities of national authorities as well as a lack of supervision of at-risk sectors (APG 2017a: 6). Due to persisting weaknesses in its AML/CFT framework, Cambodia was grey listed by FATF in 2019, but in February 2023 was delisted (FATF 2023). Nevertheless, research from Transparency International Australia (2024:2) found significant IFFs vulnerabilities persist in Cambodia, citing many of the same risk factors including its cash-based economy, geographical position and levels of corruption, noting Cambodia’s consistently low ranking on the CPI.

UNODC (2024c) found Cambodia was one of the SEA counties where there was a significant money laundering risk associated with its casino industry. In addition to casinos, the US State Department cautioned against illicit finance risks associated with Cambodia’s financial, real estate and infrastructure sectors (Office of Foreign Assets Control 2021).

Cambodia is a regional hub for multiple predicate crimes, which, as GI-TOC (2023b: 3) highlights, have wider development impacts. For example, GI-TOC points out that Cambodia is one of the world’s major producers of counterfeit goods, including products that pose health risks, and that the illegal logging and timber trade contributes to Cambodia having one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world. These crimes are often perpetrated by regional criminal networks, meaning their proceeds are then transferred across borders. For example, Chinese actors are reportedly instrumental in the smuggling of Cambodian rosewood timber into China (GI-TOC 2023b: 3). Conversely, other crimes mainly perpetrated by domestic criminal actors draw in illicit funds sourced from other countries in the region. For example, Cambodia hosts large-scale cyberfraud compounds that target victims throughout Asia (GI-TOC 2023b: 4).

There have also been reports of high levels of tax evasion by domestic actors. Analysing the involvement of multiple Cambodians in schemes exposed in the Panama Papers leak, Men (2016) reports that ‘Cambodia’s lax regulatory environment and tax loopholes mean the scale of offshoring and its economic impact on the Southeast Asian country remain unknown’. GI-TOC (2023b: 4) argues that high levels of tax evasion are facilitated by the country’s persistent patronage system.

Indonesia

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

Upper middle income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

15,415.6 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.713 out of 1 Ranking: 112 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Recommendations

Immediate Outcomes

(APG 2023f) |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 6.85/10 Ranking: 20 of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

Score: 37/100 Ranking: 99 of 180 countries |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 5.33 Ranking: 78 of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

18.8% |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

Inflows: 20743 Outflows: 23310 Net outflows: 2566 |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

0.3% |

Indonesia is an upper middle-income country. The indicators suggest it has low offshore wealth rates, low money laundering risks and a perceived corruption level in the mid-range, with high rates of criminality.

In its 2023 MER, the APG determined that Indonesia’s money laundering risks primarily stem from domestic proceeds, but that the country is not a major destination jurisdiction for foreign illicit proceeds (APG 2023f: 5). It highlights that higher risks are associated with predicate offences of narcotics trafficking, corruption, financial crimes and taxation, and forestry related crimes.

However, it also notes that Indonesia is a primary source and destination country for terrorism financing risks in the region, due to the presence of domestic terrorist organisations such as Darul Islam and Jemaah Islamiyah (APG 2023f: 5). These receive donations and other payments from domestic and foreign sources, often exploiting online banking, mobile payments and formal and informal money value transfer systems (APG 2023f: 5). Beyond the impacts on human security, evidence suggests that attacks and activities perpetrated by these terrorist organisations also discourage economic development in Indonesia (Golose 2023).

Manzi (2020: 2) argues that illicit financial flows act as a driver for various environmental crimes in Indonesia, such as illegal logging, palm oil plantations and wildlife trafficking, which cause rapid deforestation and threaten the country’s biodiversity. Furthermore, illicit mining for gold and other metals has been associated with poor safety standards for workers (GI-TOC 2023c: 5). These environmental crimes are often enabled by collusion between elites controlling land and private sector actors (GI-TOC 2023c: 5). Many products are trafficked through established routes from Indonesia to the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore, and then to the global market (UNODC 2016: 36).

However, legal tax avoidance practices are also linked to Indonesia’s natural resources. A report by Forum Pajak Berkeadilan et al. (2020: v) attests to the widespread practice of Indonesian companies in the pulp and paper industry shifting profits to Macao, an offshore tax haven. They argue this contributes to ‘Indonesia’s low tax collection rates, which limit the country’s potential to fund infrastructure development, social welfare programs, pandemic response, and other fiscal priorities of the government’. Similarly, Financial Transparency Coalition (2020: 24) highlights the case of Jakarta-based firm Adaro Energy, one of the largest coal producers across SEA with has revenues of over US$3 billion, and an offshore presence in well-known secrecy jurisdictions which could indicate tax-based IFFs.

There have been some country-specific efforts to measure the scale of IFFs from Indonesia. GFI (2019b: iv) carried out a dedicated study on Indonesia, and using its aforementioned methodology, identified ‘potential revenue losses associated with trade misinvoicing’ of over US$6.5 billion in 2016, which was equal to about 6% of total tax collected in the same year. Also using the GFI methodology, the Prakarsa (2023) identified discrepancies related to trade in fisheries and coal, calculating losses of US$5.58 billion over a period of ten years. In their study of tax-related IFFs, the Prakarsa (2019) concludes both tax evasion and tax avoidance practices contribute to Indonesia’s low tax revenue.

Lao PDR

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

Lower middle income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

9,291.8 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.620 out of 1 Ranking: 139 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Greylisted as of April 2025. Recommendations

Immediate Outcomes

(APG 2023g) |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 6.12/10 Ranking: 46 of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

Score: 33/100 Ranking: 114 of 180 countries |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 7.53 Ranking: 6 of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

16.4% |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

Inflows: 193 Outflows: 127 Net outflows: -65 |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

1.4% |

According to the indicators, Lao PDR is a lower middle-income country with one of the lowest GDP per capita (PPP) rates and HDI scores in the region. Furthermore, the indicators suggest reasonably high rates of criminality and perceived corruption, and high money laundering risks.

In its 2023 MER, the APG determined that since Lao PDR was not a regional financial centre, it faced lower risks of being used as a destination for criminal proceeds, but nevertheless constitutes a transit location for criminal proceeds, noting its ‘geographic proximity to higher ML/TF risk jurisdictions in the ASEAN region that exposes it to foreign illicit financial flows’ (APG 2023g:5). For example, it found that ‘Lao PDR continues to face globally significant risks from illicit proceeds generated by drug production and drug trafficking in the so-called Golden Triangle region’ (which encompasses the bordering areas of Lao PDR, Myanmar and Thailand) along with illicit proceeds generated from a range of crimes including corruption, arms trafficking and human trafficking (APG 2023g:6). The MER also noted weaknesses of national authorities’ understanding of ML risks (APG 2023g:6); Lao PDR was grey listed by FATF in February 2025 (FATF 2025).

The GI-TOC (2023d:4) also notes that Lao PDR serves as a major transit hub for narcotics trafficking, particularly for synthetic drugs and heroin trafficked from Myanmar. It highlights that Lao PDR ranks among the top ten countries globally for the illegal wildlife trade; for example, ivory and other internationally protected species such as pangolins often enter Asian markets through Lao PDR. Furthermore, Lao PDR is known for being a source, transit and destination country for human trafficking, including for purposes of forced labour and sex (GI-TOC 2023d:3). GI-TOC (2023d:5) concludes that corruption is a pervasive issue in Laos, and that many state actors are involved facilitating these criminal markets (GI-TOC 2023d:5).

UNODC (2024c: 26-27) highlights that Lao PDR’s SEZs, including those hosting casino complexes, have been exploited for money laundering and to traffic narcotics, gold and other products. One of the most notorious cases is the Golden Triangle SEZ, located in the eponymously named region bordering Myanmar and Thailand, which is reportedly regularly used to launder millions of dollars of criminal proceeds. The SEZ is reportedly run by Chinese criminal actors, but the national government maintains an equity stake (International Crisis Group 2023).

A study from Mehrotra et al. (2020: 1) finds that, while Lao PDR is one of the fastest developing countries in Asia, levels of domestic revenue mobilisation remain low, including because of commodity-trade related illicit financial flows. Sisouphanthong et al. (2024) argue Lao PDR is ‘a developing country with abundant natural resources but less effective legal frameworks for tackling IFFs’. In their study, they attempt to estimate the extent of trade mispricing in some of Lao PDR’s key exports. They estimated that between 2012 and 2017, trade mispricing for the country’s gold and copper exports for the period 2012–2017 accounted for losses of US$396.6 million, and US$522.3 million for coffee and rubber exports between 2014 and 2020. They also assessed Lao PDR’s legal framework on tax collection and found it weaker than those of other ASEAN member states.

Malaysia

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

Upper middle income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

36,416.5 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.807 out of 1 Ranking: 63 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Recommendations

Immediate Outcomes

(APG 2018a) |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 6.23/10 Ranking: 38 of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

Score: 50/100 Ranking: 57 of 180 countries |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 5.50 Ranking: 67 of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

20.8% |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

Inflows: 32284 Outflows: 31004 Net outflows: -1280 |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore Wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

4.3% |

Malaysia is an upper middle-income. The indicators suggest moderate to high levels of exposure to criminality, money laundering risks and perceived corruption. In terms of IFFs linked to trade misinvoicing, Malaysia has consistently had one of the highest value gaps in the world as measured by GFI (2021).

The APG’s MER of Malaysia is from 2015 and found that ‘Malaysia’s geographic position, the size and nature of its open economy, relatively porous borders and domestic and regional crime threats’ contribute to ML and TF risks (APG 2015: 8). Due largely to the global threat posed by Islamic State at this time, it also experienced heightened terrorist financing risks, including the financing of the movement of foreign fighters from or through Malaysia to the Levant (APG 2015: 8). In a more recent assessment, the US Embassy in Malaysia (2024) noted that while Malaysia continues to be a transit country for members of terrorist groups, no terrorist incidents were reported in 2023, and the government was engaged in multiple efforts to counter terrorism and terrorist financing.

GI-TOC (2023e: 3) highlights that Malaysia’s geographic location – especially the Strait of Malacca – is exploited for various predicate crimes, including the smuggling of small arms and light weapons, narcotics trafficking and illicit trade. Furthermore, GI-TOC (2023e: 3) highlights that wildlife trafficking and illicit gold mining are major issues in Malaysia, causing significant environmental damage (GI-TOC 2023e: 4). A World Bank (2019) report highlights the issue of large-scale illicit tobacco smuggling in Malaysia and the negative effects it has on youth health.

The1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) case serves as an example of the severe development ramifications of a grand IFFs scheme. Billions of dollars were embezzled from a sovereign wealth fund, enabled by corrupt state actors, and subsequently laundered through other sovereign wealth funds and state-owned enterprises in the Gulf states, before being used to purchase properties and luxury goods, including in the US (Vittori 2021: 23). Azmi (2025) highlights that Malaysia had to issue government bonds valued at up to US$10.82 billion to service debt incurred by the 1MDB scandal, which could have been used to construct 94 hospitals or 558 schools instead. He also argues that Malaysia’s standing as a desirable investment destination was undermined, leading to other potential losses. GI-TOC (2023e: 4) concludes that Malaysia remains vulnerable to the misappropriation of government funds, as well as other forms of financial crime, including a surge in online fraud.

Myanmar

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

Lower middle income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

5,953.4 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.608 out of 1 Ranking: 144 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Blacklisted as of April 2025. Recommendations

Immediate Outcomes

(APG 2024c) |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 8.15/10 Ranking: 1st of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

Score: 16/100 Ranking: 168 of 180 countries |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 8.17 Ranking: 1 of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

21.4% |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

Inflows: 982 Outflows: 486 Net outflows: -497 |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

0.2% |

Myanmar has lowest GDP per capita (PPP) in the region, as well as the lowest HDI score, suggesting its faces some of the most acute development challenges in the region. It was notably given the highest criminality and ML scores on the GI-TOC and Basel indices respectively.

The APG’s most recent MER of Myanmar is from 2018 and highlighted the prevalence of a range of predicate crimes, including drug production and trafficking, environmental crimes (including illegal jade mining, wildlife smuggling and illegal logging), human trafficking, corruption and bribery (APG 2018b: 3). These risks largely persist, and the situation is seen as having deteriorated since the 2021 military coup. In October 2022, FATF blacklisted Myanmar, where it remains as of April 2025 (FATF 2025).

According to GI-TOC (2023f: 5) the Tatmadaw – the military government – relies on illicit economies to finance its operations, and aligns with various militias and criminal groups for this purpose, meaning many criminal activities, corruption and complicity. MacBeath (2025: 2) finds ‘illicit economies in Myanmar are deeply intertwined with the country’s political structures and conflict dynamics’ and, in addition to financing armed groups, they can engender competition between ethnic groups over these economies. There is a strong cross-border element to Myanmar’s illicit economics, with GI-TOC (2023f: 5) noting the widespread involvement of Chinese groups.

Myanmar faces acute IFF risks linked to its rich deposits of minerals. Illicit jade mining is a lucrative industry in Kachin State, and was used as a source of income for the military before and after taking power (Lain et al. 2017:15) Lain et al. (2017:15) and Amerhauser (2023: 15) describe the key role of Chinese actors in the market, who have used manipulation practices and shell companies to escape taxes, amassing significant revenue losses for Myanmar. Global Witness (2024) documents how, in recent years, there has been also a spike in heavy rare earth elements sourced from Myanmar, with an estimated value of US$1.4 billion in 2023; this continues to be largely controlled by and helps sustain illegitimate military-aligned militia groups. Illicit mining in Myanmar has been associated with environmental damage such as river erosion and the destruction of farmland (GI-TOC 2023f: 4).

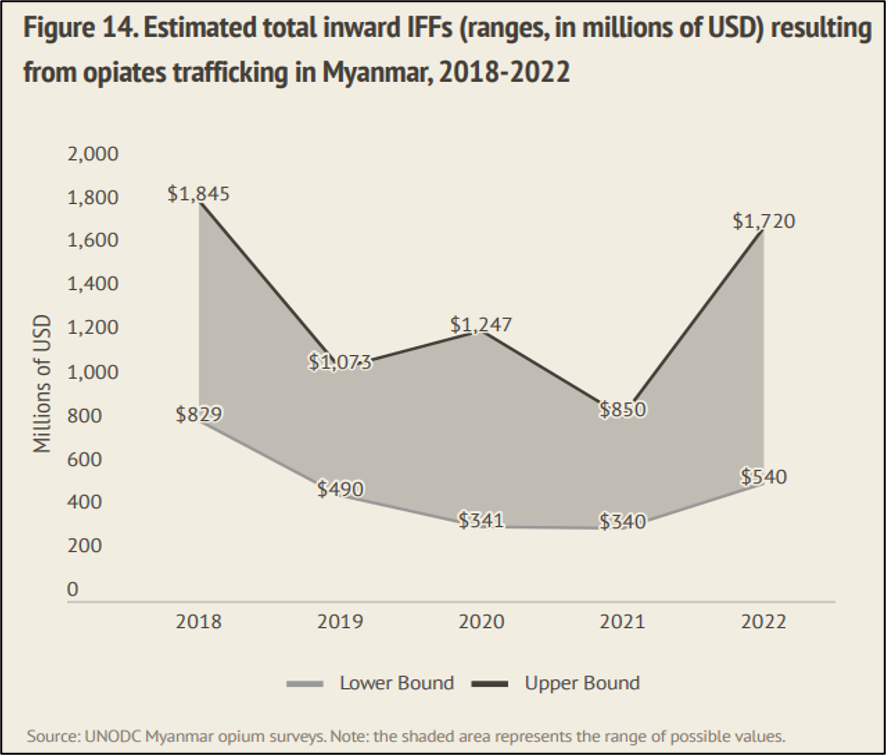

Myanmar is a major source country for narcotics, including synthetic drugs produced for widespread export (GI-TOC 2023f: 4). In 2021, it overtook Afghanistan as the world’s largest producer of opium, and UNODC has produced estimates of IFFs resulting from opium trafficking based on data from its Myanmar opium surveys (UNODC 2023b). Aside from Vietnam, this currently constitutes the only case of the UNODC/UNCTAD methodology being applied to an ASEAN country (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: UNODC’s estimates of incoming IFFs from opiates trafficking in Myanmar

Credit: Source: UNODC 2023b: 17

Myanmar contends with high rates of illegal logging and timber trafficking to China, especially teak. Amerhauser (2023: 15-16) explains that this undermines local livelihoods and the country’s fiscal security due to losses incurred from unpaid taxes and tariffs and corrupt payments. Similarly, Mahadevan (2021: 1) notes that illicit timber trafficking from Myanmar to China has been responsible for rapid deforestation.

Myanmar is furthermore a source and destination country for arms trafficking, driven by the military government and armed groups opposing them (GI-TOC 2023f: 3). In a 2023 report by the UN special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, it was estimated that since the coup the military government had circumvented sanctions and imported at least US$1 billion in arms and raw materials to manufacture weapons (OHCHR 2023).

Philippines

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

Lower middle income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

10,988.6 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.710 out of 1 Ranking: 113 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Recommendations

Immediate Outcomes

(APG 2022b) |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 6.63/10 Ranking: 25 of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

Score: 33/100 Ranking: 114 of 180 countries |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 5.84 Ranking: 49 of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

26.1% |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

N/A

|

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

2.4% |

The Philippines is a lower middle-income country with a mid-range HDI score. The indicators suggest reasonably high levels of perceived corruption and criminality. In the 2021 GFI dataset, the Philippines recorded one of the highest value gaps globally (26.1% as a percentage of total trade).

In its 2019 MER, the APG (2019a: 7-8) flagged that significant illicit proceeds were generated in the Philippines from predicate crimes such as corruption and narcotics trafficking, often with the involvement of organised criminal groups. It also found the Philippines was exposed to terrorism and TF risks because of the presence of domestic networks supporting both. In 2021, the Philippines was placed on the FATF grey list before being removed in 2025 (FATF 2025).

The US Department of State (2023) noted the continued threat of terrorist groups – notably the Communist Party of the Philippines and various Islamist affiliate groups – and estimated 95 terrorist attacks resulting in 299 victims over the course of 2023. It also noted persistent terrorist financing risks, with 30 cases involving 13 defendants being filed for prosecution in that year (US Department of State 2023). Osorio (2024: 55) describes how domestic terrorist groups like the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) engaged in various forms of illicit economies to fund their operations.

The Asian Peoples’ Movement on Debt and Development (APMDD) (2024:3) states that the Philippines’ low tax-to-GDP ratio is compounded by foregone revenues from illicit financial flows. It also notes that over 940 individuals and companies with Philippine addresses were listed in the Pandora Papers leak, suggesting wealth is transferred offshore (APMDD 2022). This includes corporations in the Philippine mining sector that have been implicated in reports on offshore accounts and subsidiaries registered in tax havens, including in the Pandora Papers revelations (Eurodad 2024: 45). Relying on the TJN’s estimates, Eurodad (2024: 45)calculated cross-border tax abuse was costing the Philippines over US$3 billion annually, corresponding to over 60% of the country’s health expenditures.

The GI-TOC highlights the prevalence of financial crimes in the Philippines and that in recent years, ‘trillions of Philippine pesos have been lost due to illegal withdrawals’ (GI-TOC 2023g: 4). In particular, they highlight cyber-enabled fraud and illegal cryptocurrency-related schemes. UNODC (2024c) listed the Philippines as one of the Southeast Asian countries where there the large and sometimes informal casino industry poses significant ML vulnerabilities.

Singapore

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

High income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) (2023) |

141,553.5 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.949 out of 1 Ranking: 9 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Recommendations

Immediate Outcomes

(APG 2019b) |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 3.47/10 Ranking: 169 of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

Score: 84/100 Ranking: 3rd of 180 countries |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 4.70 Ranking: 110th of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

N/A |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

Inflows: 41603 Outflows: 32043 Net outflows: -9560 |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

25.3% |

Singapore is the most economically developed country in the ASEAN region. It is a strong performer on the CPI but performs weakly on the Basel Index for AML. In the ASEAN region, Singapore received TJN’s highest estimate of offshore wealth owned by citizens: 25.3% of GDP.

In its 2016 MER report, while the APG recognised that Singapore’s status as a financial and wealth management centre made it vulnerable to becoming a transit country for illicit funds from abroad, noting that 77% of the funds managed in Singapore were foreign sourced, with the majority of assets under management coming from the Asia-Pacific region (APG 2016a: 5). It also recognised Singapore’s position as an international trade/transportation hub increases its ML/TF vulnerabilities. In a subsequent report on ML typologies, APG (2024a: 31) noted Singapore faced challenges with criminals exploiting shell companies to facilitate illicit transactions, often established with the support of corporate service providers (APG 2024a: 31), and that Singapore remains vigilant to the potential ML risk arising from the wealth management sector (APG 2024a: 75).

Other observers have reached similar conclusions. Lain et al. (2017:2) considers Singapore as one of the leading financial centres that facilitates IFFs. An analysis carried out by Transparency International (2025) of cases of IFFs linked to corruption originating in Africa found that enablers registered in Singapore were often complicit, attributable in part to inadequate supervision of such professions. Indeed, some of the key offshore financial service providers named in the Pandora Papers leak were registered in Singapore (Amerhauser 2023: 11).

Langdale (2025) states that counterfeit goods are trafficked from China to Europe through Singapore’s port. Also, the country is a leading trader in commodities, which are vulnerable to IFFs, particularly given that Singapore is the third-largest global oil trading hub (Langdale 2025). Singapore hosts free trade zones too, which are reportedly exploited for illicit trade, including in illegal wildlife products (The Economist Intelligence Unit 2018: 19; Langdale 2025). Khan et al.’s study (2021: 144-45) relied on GFI trade discrepancies data from 2002 to 2014 for 156 countries and found that the most attractive destination country for trade-related IFFs was Singapore.

Langdale (2025) argues that rising transnational crime in SEA has negative spillover effects for Singapore. In 2022, Singaporean authorities found that Chinese criminal actors had laundered US$2.2 billion in proceeds from online gambling and scamming operations in Cambodia and the Philippines, including through cryptocurrencies (Langdale 2025). While Singapore is known for its low domestic crime rate (Themis 2023), predicate crimes do occur on Singaporean territory. The GI-TOC (2023h:3) also notes that ‘human trafficking remains a widespread problem in Singapore, particularly in the construction, mining and domestic work industries’, and that victims often come from other SEA countries.

Thailand

|

Indicator |

Classification/score |

|

World Bank country classification by income level (2024-2025) |

Upper middle income |

|

GDP per capita, PPP (current international US$) |

23,465.1 |

|

Human Development Index (2022) |

Value: 0.803 out of 1 Ranking: 66 of 193 countries |

|

Current level of compliance with FATF Recommendations and Immediate Outcomes |

Recommendations

Immediate Outcomes

(APG 2023h) |

|

The Global Organized Crime Index 2023: Criminality Score |

Score: 6.18/10 Ranking: 44 of 193 countries |

|

Corruption Perceptions Index 2024 |

Score: 34/100 Ranking: 107 of 180 countries |

|

Basel AML Index 2024 |

Score: 6.16 Ranking: 41 of 164 countries |

|

Global Financial Integrity estimates of Trade-Related Illicit Financial Flows (2009-2018): value gaps as a percent of total trade |

19.7% |

|

ESCAP calculations of trade misinvoicing flows in Asia-Pacific, 2016 |

Inflows: 25680 Outflows: 30114 Net outflows: 443 |

|

Tax Justice Network estimates of offshore wealth owned by citizens of country (% of GDP) (2024) |

3.7% |

Thailand is an upper middle-income country. The indicators suggest it faces reasonably high rates of perceived corruption, criminality and ML risks.

The APG’s most recent MER of Thailand was carried in 2017, and found the open cash-based economy, the high level of international trade and investment, and porous borders all gave rise to ML vulnerabilities, as well as highlighting the risks posed by the predicate crimes of corruption, drug offences, tax evasion, customs evasion and unfair securities trade (APG 2017b: 5).