Corruption5b119773509f undermines the effectiveness, quality, and accessibility of healthcare by diverting funds and resources. It also deepens existing inequities, with women and marginalised groups disproportionately affected when they face demands for informal payments to access maternal health or other essential services (Coleman et al. 2024). Forty-five per cent of citizens globally consider their health sector to be corrupt or extremely corrupt, with a lack of transparency in how services are governed and delivered. This provides fertile ground for both inefficiency and abuse (OECD 2017). Corruption and fraud strip health systems worldwide of an estimated US$560 billion each year (Wright 2023).

Despite clear evidence of these harmful effects, there appears to be relatively little action from bilateral and multilateral development agencies to address corruption specifically within the health sector. This U4 Report seeks to understand this gap. Our research found that interventions commissioned by development agencies were often either broad governance reforms, or specific and targeted initiatives. This finding is also not unique; previous research has similarly identified a lack of comprehensive medium- and long-term programmes targeting corruption in the health sector. Instead, initiatives tend to focus on specific problems (eg informal payments), single processes (eg drug procurement), or individual institutions (eg hospitals or health centres) (Hussman 2020).

To investigate this issue, we undertook a three-stage review process. We analysed the strategies of 19 bilateral and multilateral development partners, including international financial institutions (IFIs). We also reviewed publicly disclosed development assistance expenditure by bilateral agencies to understand their priorities and investments in anti-corruption, transparency, and accountability (ACTA) within health-related work and programmes. We then conducted open-ended interviews with 22 key informants from these institutions to understand the barriers and opportunities for action. Finally, we conducted two case studies in Zambia and Bangladesh to examine how multilateral agencies work on this issue at the country level. These countries were chosen as they represent different contexts in terms of government prioritisation of anti-corruption and development partner engagement.

We outline our methodological approach and main findings across these areas, before concluding with recommendations for development agencies and their partners to increase action on this critical issue.

1. Methodology

From October 2023 to November 2024, the authors undertook desk-based strategy reviews, International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) analysis, and key informant interviews. The aim was to examine how and where development partner and multilateral agencies have been investing in ACTA in health.

The authors analysed IATI data and then undertook strategy reviews. The results of these two analyses were then used to conduct semi-structured interviews with 22 key informants across development partner and multilateral agencies. This enabled the research to assess the strategic focus of development partners and multilateral agencies in relation to both anti-corruption and health, and to examine the levels and types of work commissioned or funded on the topics.

i. Strategy reviews

We reviewed policy and strategy documents from ten bilateral development partner agencies and nine multilateral agencies and IFIs, to understand the extent to which these agencies prioritise ACTA in their development assistance, and if – and how – they integrate such measures in health programmatic work. Our review examined all relevant public documents for each development partner, including overarching international development strategies and specific global health policies.

A full list of the organisations reviewed is shown in Table 1. The agencies were selected based on their current partnership with the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, association with the Global Network on Anti-Corruption, Transparency and Accountability in Health (GNACTA), and their role as major funders in global health. The review researched strategies that were current as of the search period.

We conducted online searches of government and relevant ministry websites to identify and collect relevant strategies. The search and review were limited to documents published in English. Once collected, we searched documents for references and keywords related to ‘anti-corruption’, ‘corruption’, ‘transparency’, ‘governance’, and ‘accountability’. In total, we reviewed 21 development partner strategies and white papers, as well as 13 development frameworks and strategies from multilateral agencies, development banks, and global initiatives.

To conduct the review, we developed a standardised review process. Development strategies were first read to identify agency priorities in: i) health; ii) ACTA; and iii) whether there was crossover between the two. Where ACTA measures were referenced in development strategies, we categorised approaches based on how they fit into four thematic areas: corruption, governance, transparency, and accountability.

We then reviewed health strategies (where available), looking for explicit mentions of ACTA, as well as health governance, community accountability, public financial management (PFM), and procurement. These are intervention areas where anti-corruption activities may be integrated. Consideration was given to the approaches used to embed ACTA into the health sector. We focused on the health system building blocks related to ACTA interventions, and recognised corruption as a barrier to: gender and inclusion; geographic focus; and – where relevant – bilateral development partner agency priorities in their support to multilateral agencies.

We also reviewed governance and/or anti-corruption strategies that were published, to ascertain where organisations were placing priorities around anti-corruption work, and if so, were proposing sector-specific approaches to anti-corruption.

We recognised that development partners structure their strategies differently. Therefore, our analysis looked at all available strategy documents for each development partner. The crucial step was to then determine if, and how, they linked these two areas. This method allowed us to see whether a development partner fully integrates anti-corruption into its health work, treats them as separate priorities, or has a limited focus on either topic.

Table 1: List of partners and strategies reviewed

|

Bilateral development partners |

Type of strategy reviewed |

Number of strategic documents reviewed |

|

Canada |

Development, health |

2 |

|

Denmark |

Development |

1 |

|

Finland |

Development |

1 |

|

Germany |

Development, health |

2 |

|

Norway |

Development, health, anti-corruption |

3 |

|

Sweden |

Development, health |

2 |

|

Switzerland |

Development |

2 |

|

UK |

Development, health, governance |

3 |

|

USA |

Development, anti-corruption |

3 |

|

European Union* |

Development, health |

2 |

|

Multilateral agencies and IFIs |

||

|

The World Bank |

Health and country-specific strategies |

3 |

|

African Development Bank (AfDB) |

Health |

1 |

|

Asian Development Bank (ADB) |

Health |

1 |

|

Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) |

Health |

1 |

|

World Health Organization (WHO) |

Programme of work |

2 |

|

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) |

Overarching strategy |

1 |

|

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) |

Overarching strategy |

1 |

|

The Vaccine Alliance (GAVI) |

Overarching strategy |

2

|

|

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (GFATM) |

Overarching strategy |

1 |

* The European Union was included here under ‘bilateral’ development partners rather than as a multilateral one, as it operates in a manner similar to a bilateral development partner in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

ii. Expenditure analysis

We used data published by IATI to analyse historic patterns of bilateral and multilateral funding of ACTA in the health sector. The IATI has the most comprehensive global dataset on development expenditure. It contains details on: what the funding was intended for; the amount; and where and when it was disbursed. Development partners upload information to the IATI database. It records commitments and disbursements of funding made to civil society organisations (CSOs), private contractors, and multilateral organisations. It also records disbursements made by development partners for funding internal programmes managed by themselves.

We extracted data from the database and retrieved more than 400,000 activities, which were the data available from 2003 to 2024 (IATI 2023). The extraction aimed to capture a comprehensive dataset of official development assistance (ODA) activities. Data were downloaded on 28November 2023.

Following extraction, we applied a filtering process to the dataset. We used a set of 170 keywords or phrases associated with ‘health’ and ‘corruption’, along with specific sector codes present within the IATI data. After applying these filters, we identified a subset of 686 activities that contained these explicit references to both anti-corruption and health activities.

We found that the reporting structure of IATI data complicates the analysis of spending on anti-corruption and health within larger development assistance activities. Many projects – often worth multi-millions of euros over multiple years – may include aspects of both anti-corruption and health. However, these elements might be minor or not directly linked. Our analysis found projects typically fell into one of two categories: broader governance initiatives that incorporate health components (usually classified under general services) or health programmes that address anti-corruption issues.

The challenge arises because IATI data do not provide detailed insights into how significantly these broad activities engage in both anti-corruption and health simultaneously. For example, a comprehensive governance project could aim to reduce informal payments within the health sector, but this specific aspect might not be distinctly outlined in the data if the project is reported in the IATI database as a single, unified activity.

To counter this, we conducted a manual review of the dataset to identify activities that had a major and observable emphasis on health and anti-corruption. An activity was defined as having a ‘major focus’ if its primary objective – as stated in its IATI title or summary – was explicitly aimed at improving ACTA within the health sector. This process allowed us to distinguish core projects from broader governance programmes where health was only one of several sectors mentioned, or from large health systems projects where ACTA was not a stated goal.

We arrived at 89 activities that worked directly towards addressing ACTA in health. Many of them related to activities where funding was provided to Transparency International Global Health (TI GH) and the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre (U4). However, there were enough activities undertaken by other recipients to provide insights.

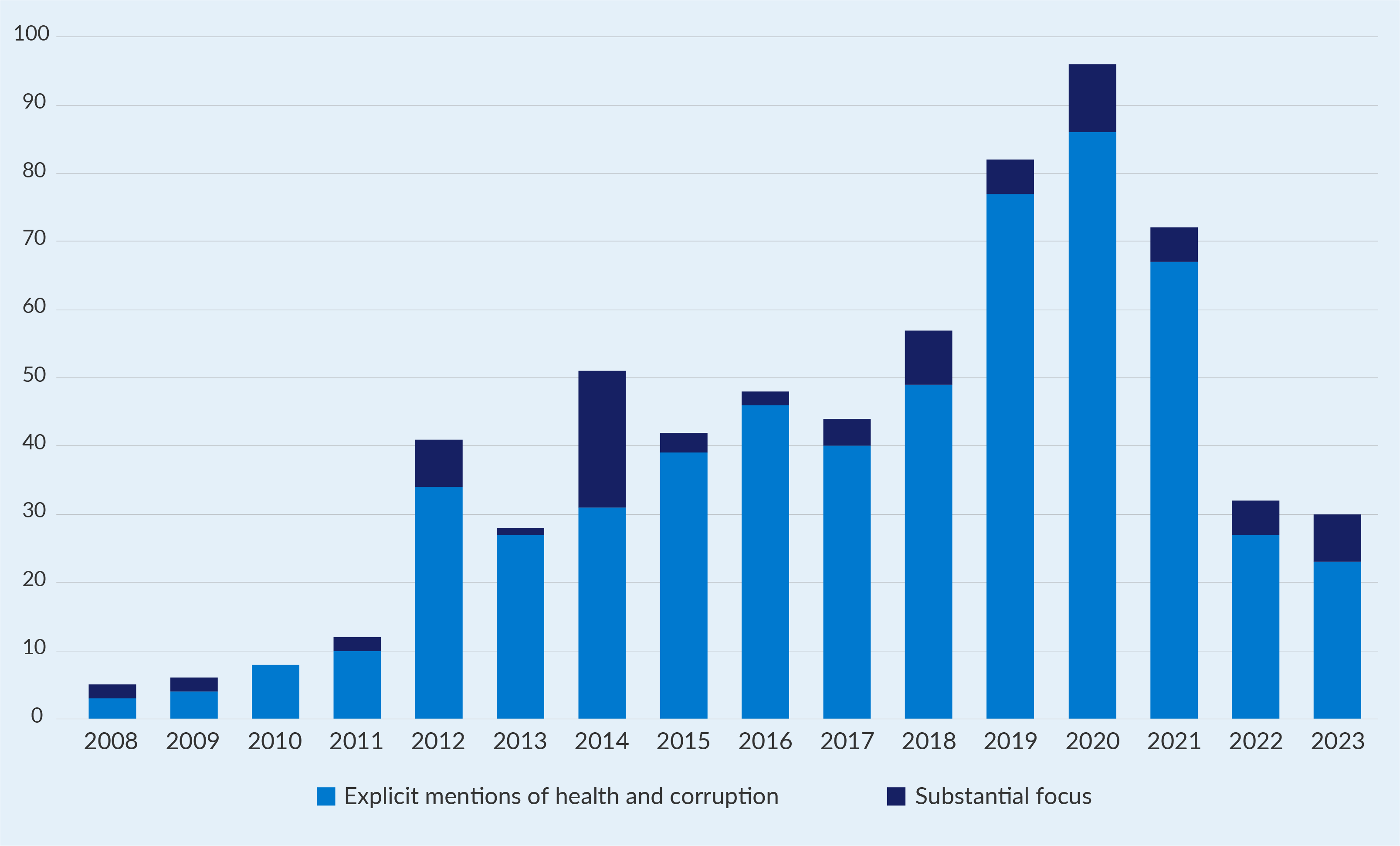

For our analysis, we categorised projects as having either an ‘explicit’ or ‘substantial’ focus. Projects with an ‘explicit’ focus were those where the primary stated objective was to improve ACTA within the health sector. Projects with a ‘substantial’ focus were broader governance or health system initiatives where ACTA was a significant named component, but not the sole focus.

Limitations of IATI data

Our analysis revealed a broader issue with the quality and completeness of data reported in the IATI database. We judged data quality based on the completeness of major fields required for analysis. Key issues included missing financial values for activities, a lack of descriptive text explaining a project’s purpose, and incomplete information on project location. These gaps mean that a full analysis of development partner investments is not always possible.

We also found that known activities were not always present in the data. Funding from the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) to TI GH and U4 did not appear. Had this funding – along with known support from Sweden and Norway to the same institutions – been fully captured, then U4 and TI GH would likely rank among the top ten recipients of funding in this area.

It is important to note that IATI data are not comprehensive. Not every development agency publishes all their information on budgets, sectors, transactions, etc. This limits analysis on the final dataset and, therefore, this report’s calculations are at best a rough estimate.

Additionally, some projects that counter corruption do not explicitly state this in their data releases. This is likely in part due to sensitivities in project design (eg using the term ‘corruption’ may be more contentious than ‘accountability’). The report categorises these as having a substantial, rather than explicit, focus on ACTA. Finally, due to the need to filter by activities that were explicitly tagged as ‘ODA’ (not doing so failed to produce results from the IATI database), some activities that did not have that tag in the relevant field may not be present in the final dataset.

These technical gaps are part of a wider challenge that has significant implications for development assistance transparency. This lack of comprehensive, comparable data is a systemic issue that hampers the ability of researchers, civil society, and development partners to fully assess investments and identify gaps.

iii. Interviews

The research included interviews to better understand the decision-making landscape, particularly where opportunities may lie for greater investment and policy positions for promoting ACTA in health. We carried out 22 semi-structured interviews with representatives from 15 bilateral development partners and 7 multilateral agencies. These individuals were selected through purposive sampling and were typically senior advisers or technical specialists who worked in the fields of either health or governance, and anti-corruption.

Due to the sensitivity of the topic, we conducted the interviews under conditions of confidentiality and anonymity in reporting. The participants gave informed verbal consent for their participation in the interviews, during which we explained the study’s purpose and confidentiality measures. To ensure confidentiality, we stored all interview data on a secure, password-protected platform. We have removed all identifying details of participants and their institutions, and – to ensure anonymity – we present the findings in aggregate. The discussions covered themes of strategic priorities, barriers to implementation, and practical challenges. The data were then analysed using thematic analysis to identify recurring patterns. The analysis suggested that data saturation was reached, as the same major themes emerged consistently across the interviews with different participants.

We managed all personal data collected for this research in accordance with Transparency International UK’s (TI-UK) Data Protection and Privacy Policy and in line with U4’s contractual obligations.af106d8b1840 This policy ensures full compliance with General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and its implementation is overseen by TI-UK’s in-house Data Protection Officer to secure all data and protect the privacy rights of participants.

iv. Case studies

The research included two in-depth country case studies to explore how development partners’ approaches to integrating ACTA into the health sector are implemented at the national level and influenced by local context.

We used a comparative case study design, selecting Bangladesh and Zambia as they represent contrasting political environments for anti-corruption work. At the time of the research, Zambia’s government had made anti-corruption a stated political priority; whereas in Bangladesh, there was less government-led impetus on the issue. This contrast allowed the analysis to explore how the political will of a host country shapes development partner engagement, the choice of partners, and the types of anti-corruption initiatives pursued.

For each case, the analysis involved a synthesis of three main sources of data:

- Document review: We analysed national policies and country-level strategy documents from major multilateral agencies and bilateral development partners to understand their stated priorities and approaches.

- Expenditure analysis: We reviewed IATI data to identify specific ACTA in health projects and funding flows directed to each country.

- Interview data: We drew on relevant findings from the 22 key informant interviews, particularly from respondents with direct experience in the case study countries.

2. Revealing the different approaches and what can undermine their success

Strategy reviews found development partners’ approaches fit into one of three categories:

- Fully integrated approaches, with the integration of ACTA into sectoral approaches considered as part of organisational priorities.

- Anti-corruption considered as a development cooperation priority, but not integrated into sectoral approaches.

- No explicit strategic focus on either health or ACTA within development or health strategies.

Meanwhile, bilateral development partners’ funding mostly went to either broad projects with a focus on health and ACTA, specific ACTA health projects, or as contributions to the central budget of a UN agency.

The analysis of multilateral agencies and IFIs’ strategies also reveals that their different institutional mandates largely shape their distinct approaches to anti-corruption and health. Few institutions, such as the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) and the World Health Organization (WHO), explicitly integrate ACTA into their health strategies. More commonly, multilateral institutions address corruption through a lens of fiduciary risk management. They work towards safeguarding their own funds rather than undertaking direct, programmatic anti-corruption work. This often results in agencies using politically neutral terms, such as ‘governance’ or ‘efficiency’, to frame interventions.

This section examines the approach of bilateral development partners towards ACTA in health, before considering the engagement of multilateral agencies and IFIs in this subject matter.

i. Bilateral development partners appear to fund few projects on anti-corruption in health

Our analysis of funding flows revealed three types of funding:

- Broad projects with a focus on health and ACTA.

- Specific ACTA health projects. This category includes projects implemented by any partner – such as a CSO or a UN agency – on behalf of a development partner.

- Contributions made to the central budget of a UN agency, which are not reserved for a specific project but where the overall funding agreement references ACTA priorities.

We analysed funding patterns by examining when projects were commissioned, who received the funds, and the geographical focus of the activities.

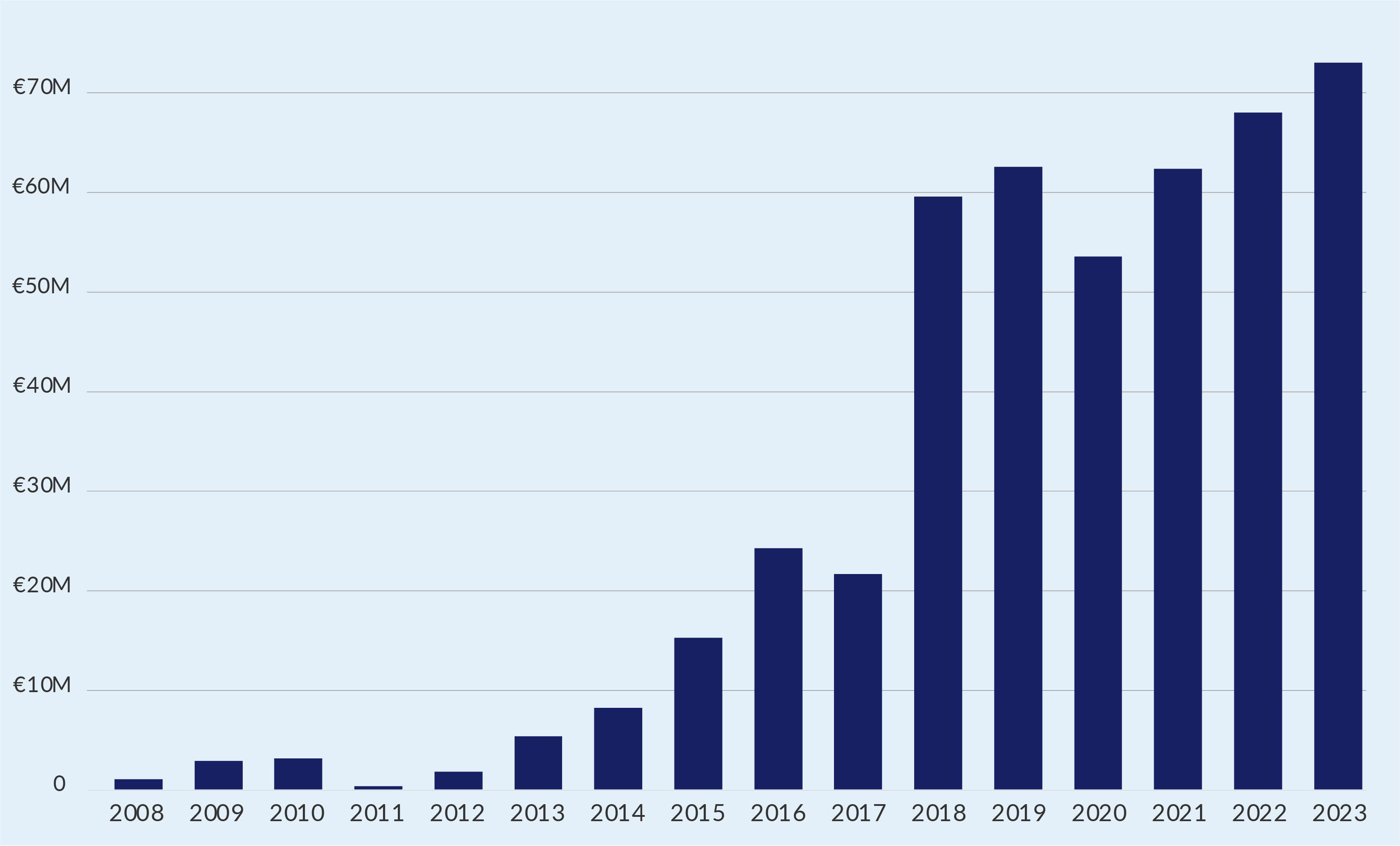

Our analysis of IATI records found comparatively low numbers of projects and activities by development partners. The expenditure data reveal that there was approximately 430 million euros worth of activities commissioned on ACTA and health over a 15-year period between 2008 and 2023 (see Figure 1). This figure is likely to be an underestimate due to the IATI data limitations explained in the methodological section. Nonetheless, to put this investment into perspective, this total amount averages just over 20 million euros per year. This is a negligible sum when compared to the estimated US$560 billion lost to corruption and fraud in the health sector each year (Wright 2023).

Yet, analysis of expenditure showed a steady increase in funding over time – although data are more limited prior to 2012. Interestingly, despite the peak in new activities commencing in 2020, the actual financial disbursements for work on ACTA in health decreased that year, possibly due to the emergency reallocation of funds to other areas to tackle the Covid-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Annual expenditure on ACTA and health

Additionally, our analysis of project commitments found that the number of new activities peaked in 2020, likely driven by interventions commissioned in response to the pandemic (see Figure 2). Before 2012, fewer activities were recorded in the IATI database, which may be due to lower overall reporting rates by development partners during that period.

Figure 2: Number of ACTA and health activities by year of initiation

The largest recipients of funding for work on ACTA in the health sector are multilateral agencies. However, this finding is heavily influenced by how large, core funding contributions are categorised. For instance, significant core support from the Danish Development Agency (DANIDA) to the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) and UN Women references terms like ‘corruption’ in the funding description. This means they are captured by the keyword search, even if specific anti-corruption work in health is not the primary focus of the funding. Multilateral agencies also seem to report when they move funding from one UN entity to another, which increases the proportion of expenditure recorded as flowing to multilateral agencies.

Overall, the data suggest that development partners use a mix of funding strategies. This involves a dual approach: commissioning smaller, targeted projects that explicitly work towards ACTA in health, while also providing much larger amounts to broad health or governance programmes where anti-corruption is just one of several objectives. This raises an important question as to whether ACTA objectives become diluted or are effectively integrated within these larger programmes.

ii. Bilateral development partners engage differently depending on their strategies

Our analysis of bilateral development partner strategies found a variety of approaches taken to embed ACTA in health activities/investments. It is important to distinguish these high-level strategic approaches – which are based on our review of policy documents – from the three types of funding flows identified in the data analysis above. Development partner approaches ranged from placing no apparent emphasis on ACTA integration to fully developed strategies for integration.

Development partner approaches fit into one of three broad categories (Table 2):

- Fully integrated: This category includes development partners whose strategies explicitly treat anti-corruption as a cross-cutting priority that is systematically integrated into their sectoral health work. For example, the strategies of Norway, Sweden, and the US purposely connect anti-corruption efforts to the health sector.

- Separate thematic priorities: Anti-corruption and health are considered high-level development priorities, but are not systematically integrated – that is, there is no specific integration of anti-corruption in health.

- Limited strategic focus: No explicit work on either health or ACTA was found within their overarching development strategies.

Table 2: Summary of approaches to ACTA in health found in strategy reviews

|

|

Fully integrated |

Separate thematic priorities |

Limited strategic focus |

|

Canada |

|

X |

|

|

Denmark |

|

|

X |

|

Finland |

|

|

X |

|

Germany |

|

X |

|

|

Norway |

X |

|

|

|

Sweden |

X |

|

|

|

Switzerland |

|

|

X |

|

UK |

|

X |

|

|

USA |

X |

|

|

|

European Union |

|

|

X |

This section highlights different bilateral development partner approaches under each category by referring to findings from the strategy reviews, IATI data, and key informant interviews. It also considers the common trends and differences among these three approaches.

Category 1: Fully integrated approaches, with ACTA mainstreamed into sectoral approaches

Strategy reviews found that Norway, Sweden, and the US explicitly integrated anti-corruption into their sectoral approaches, including health (Norad 2020; Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs 2023; USAID 2023). Norway’s government-wide development policy considers anti-corruption as a cross-cutting issue across its entire development portfolio. Anti-corruption, alongside other topics including climate change mitigation and gender, is required to be mainstreamed into all Norwegian development programming efforts (Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2017).

Sweden’s new development policy makes specific reference to the need to address corruption to ensure sustainable health financing (Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs 2023). This policy calls for the integration of accountability, transparency, and anti-corruption measures. The Government of Sweden’s global health policy references the need to tackle corruption as an overarching ambition in the health sector (Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2018b), as does Sweden’s strategy for sexual and reproductive health (Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2022). However, neither provides details as to how the country plans to implement ACTA measures into programming.

The Biden administration elevated anti-corruption to a core US national security interest (The White House 2021), recognising the detrimental impact of corruption on development outcomes.971b0b9ac1f5 To support this, the country drafted a specific anti-corruption policy (USAID 2022a), with institutionalisation of anti-corruption across US development efforts being one of the main priorities. The US Agency for International Development (USAID) published guidance on integrating anti-corruption into health sector programming. This was to be used by USAID missions and programmes in designing and implementing programmes of support in recipient countries (USAID 2022b).

The IATI data provide further insight into how these strategic priorities are allocated, revealing distinct funding patterns for each of the three development partners. The US primarily funds large, top-down governance projects implemented by commercial firms; Sweden provides smaller, bottom-up grants to civil society; and Norway supports global-level, norm-setting initiatives.

IATI data revealed that US support – through USAID and the US Department of State – comprised 24 recorded activities, accounting for approximately 145 million euros in support. It should be noted that activities recorded in IATI data cover a period prior to the launch of the USAID anti-corruption policy and its handbook in 2023. So, the impact of this policy is not reflected in IATI data. Most US expenditure mainly involved support for broad multi-million-dollar governance programmes. As these are broad projects, the full project value is recorded in IATI, which likely overestimates the specific portion directed only to ACTA in health. Funding is principally provided to commercial consulting firms (such as DAI, Chemonics, and Intrahealth) to carry out the work. Most of these activities were categorised as ‘governance’ interventions, with health mentioned as a sub-category. Some examples include:

- The Nigerian State2State project: This project works with selected states and local governments to improve the governance of primary healthcare due to poor governance, corruption, and weak institutions, and limited basic service delivery at the state and local levels. It is implemented by DAI (27 million euros) (USAID 2020).

- The Paraguayan Democracy and Governance project: This project strengthened management and governance systems in institutions to address corruption and improve services. Assistance helped major service delivery institutions, including the Ministries of Education, Health, and Finance (22 million euros) (USAID 2014a).

- The Nigerian Strengthening Advocacy and Civic Engagement (SACE) project: This project increased citizen participation in democratic processes and promoted transparency and accountability in governance in major social sectors such as health. It was implemented by Chemonics (17 million euros) (USAID 2014b).

In contrast, the IATI data recorded a total of 13 activities by Sweden through the Swedish International Development Corporation Agency (Sida). These included grants to CSOs to strengthen accountability and monitoring (eg in Zambia and Bangladesh), as well as support to Population Services International (PSI) in Zimbabwe for Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR), where corruption was mentioned. Examples include:

- Bangladesh Health Watch (BHW): This project intends to play a wider and stronger role in raising issues and concerns facing the national health sector. It suggests solutions, and supports and lobbies the government to help achieve its programmatic goals (no reported amount) (Sida 2019).

- Support to the Fojo Media Institute for a freedom of expression project: This will enable the creation of innovative Information and Communications Technology (ICT) tools to increase the accessibility of reporting corruption related to local government budget allocations within the health and education sectors in selected provinces in Uganda and Zambia (no reported amount) (Sida 2012).

Finally, Norwegian-recorded support – which referenced both health and ACTA – comprised two activities over the period from 2003 to 2024: support to the Global Network for Anti-Corruption, Transparency and Accountability in Health (GNACTA), recorded in 2020; and support to Chr. Michelsen Institute/U4 Anti-Corruption Research Centre (CMI/U4). In total, this support amounts to approximately 3.5 million euros. As these specific activities were not a focus of the interviews conducted for this research, their implementation details were not discussed. The IATI data confirm two transactions were recorded, but are not specific on how the funds were spent:

- Support to the GNACTA to work on corruption and fraud prevention in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic (16 million NOK) (Norad 2020).

- Support to CMI/U4 to identify and propose informed solutions to partners for reducing the harmful impact of corruption on sustainable development (20.5 million NOK) (Government of Norway 2017).

These distinct funding patterns reveal that each of the three development partners is pursuing a different theory of change. The US, with its large governance contracts to commercial firms, focuses on top-down institutional reform. This approach assumes that strengthening central government systems and improving management in key ministries is the most effective way to reduce opportunities for corruption in the health sector.

In contrast, Sweden’s grants to CSOs in countries like Zambia and Bangladesh reflect a bottom-up theory of change. This strategy is built on the idea that empowering citizens, local media, and community groups to monitor services and demand transparency creates powerful domestic pressure for reform – holding health systems accountable from the local level up.

Finally, Norway’s support for global bodies like the WHO and the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre points to a focus on building global norms and networks. This approach works on the principle that establishing international standards, shared knowledge, and high-level consensus is a prerequisite for driving effective anti-corruption action at the national level. These different strategies appear to be practical responses to the challenges key informants raised, such as how to advance an anti-corruption agenda when partner governments do not prioritise it.

Category 2: Development partners with anti-corruption and health as separate development cooperation priorities

Strategy reviews found that Canada, Germany, and the UK consider both health and anti-corruption as development cooperation priorities (BMZ 2023a; FCDO 2023; Global Affairs Canada 2017). None of the three countries appears to integrate anti-corruption into their health sector strategies.

Canada’s development policy (Global Affairs Canada 2017), which was the most recent available for this review, does not refer to addressing corruption, but talks more broadly about the need to strengthen the rule of law and ensure female political participation. Canada’s health strategy (Global Affairs Canada 2019) makes no direct reference to anti-corruption as a priority area either, but access to services for the most marginalised is a priority area – both for health and sexual and reproductive health services. For instance, this priority could be leveraged to support community accountability mechanisms that monitor service delivery. This would give marginalised groups a greater voice in holding health providers to account and reduce corruption at the local level.

Germany’s development policy (BMZ 2023b) considers corruption as a driver of gender-specific inequality and supports partner countries in transforming social norms that are associated with discrimination and corruption in order to counter inequality. Anti-corruption is also one of the six quality criteria that the Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) uses to assess development cooperation programmes. Programmes are therefore meant to consider corruption and be designed in a manner to counter corruption. Germany’s health policy makes broad reference to supporting sustainable health financing systems and the need to tackle corruption in the sector. Yet it does not go into detail on how it intends to do this, nor where the country should focus efforts in this area (BMZ 2023a).

The UK makes explicit reference to addressing corruption in its 2023 white paper on international development (FCDO 2023b). The paper places a heavy emphasis on addressing grand corruption and stemming cross-border capital flight. It emphasises that the UK will work further with IFIs to embed anti-corruption approaches into their strategies and operational approaches; however, there is no discussion in the paper around the need to address corruption within sectors. Nonetheless, it also refers to plans to pilot a whole-of-government approach to addressing corruption in five unnamed partner countries, which, although not stated, could potentially include sectoral approaches (FCDO 2023b).

None of the UK’s three white papers on global health places significant emphasis on ACTA (FCDO 2019; 2021; 2023a). The ‘Ending preventable deaths’ approach paper (FCDO 2021) contains broad references to increasing work on systems strengthening to enhance accountability. It also mentions increasing work with community-based organisations (CBOs) to expand community voice and empower communities. However, there is no mention of corruption in the document.

While the strategies of these three funders do not explicitly discuss or mandate anti-corruption within the health sector, their funding data reveal a more complex reality. The IATI records show that all three countries have funded specific anti-corruption measures in health projects. This suggests that while there is no systemic, internally driven policy for sectoral integration, these development partners are willing to engage on the issue opportunistically – often by channelling support through expert external partners like CSOs and multilateral agencies. The analysis of these funding patterns reveals differing approaches among the UK, Germany, and Canada.

The UK’s FCDO disbursed approximately 20.7 million euros in funding for ACTA in health over the period analysed. Funding was provided to broad sector-based projects that looked at both health and governance, including:

- Nepal’s National Health Sector Programme III: This supported governmental budgeting in the following sectors: anti-corruption organisations and institutions, basic nutrition, health policy, and administrative management (7.4 million euros) (FCDO 2014).

Funding had also been provided by FCDO for direct work on corruption in health, including:

- Transparency International’s Open Contracting in Health Systems: This is a global programme to improve open contracting in health through tools, technical support, advocacy, and peer learning (3.3 million euros) (FCDO 2017).

- Medicines Transparency Alliance: This is an alliance of partners working to improve access to medicines by increasing transparency and accountability in the healthcare market. (8.2 million euros) (FCDO 2011).

The distribution of these funds indicates that FCDO (then the Department for International Development (DFID)) considered ACTA in health to be a priority. Both these projects were commissioned before the introduction of the current FCDO white papers.

Funding provided by BMZ appeared more limited in the number of transactions recorded, with a total volume of 1.2 million euros captured in the IATI data. This included a transaction to the WHO for a project entitled Good Governance in the Health Sector, Phase III.This aimed to strengthen the health sector to prevent corruption and mismanagement, with emphasis on the pharmaceutical sector (1.2 million euros) (BMZ 2014). It is possible that the structure of the German development cooperation, with significant proportions of BMZ funding being allocated to the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) or funded through Germany’s state-owned development bank (KfW), may mean that data are not being fully recorded in IATI.

Analysis of Canada’s IATI records found 5.3 million euros of investment that could be categorised as ACTA in health. Funding was allocated to one project:

- Transparency International’s Inclusive Service Delivery Africa: This project aims to address the impact of corruption in access to education and health services for groups at risk of discrimination – particularly women and girls – in five countries in Africa (Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Madagascar, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe) (5.3 million euros) (Global Affairs Canada 2022).

Category 3: Development partners with no explicit strategic focus on either health or ACTA

Denmark, the European Union, Finland, and Switzerland fit into this category. The four had different strategic approaches. Denmark and Finland’s development strategies do not appear to prioritise health, while the EU and Switzerland include global health in their strategies but do not appear to have anti-corruption or governance strategies. Our analysis did not find any of the four development partners linking the two sectors in their strategies.

Denmark’s development strategy does not include the health sector as a priority area (Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2021). It does, however, consider addressing anti-corruption through governance support for accountability, decentralisation, and local participation. This strategic approach lacks a specific sectoral focus and, consequently, there is no mention of integrating anti-corruption measures into health systems strengthening.

Finland’s development strategy does not appear to specifically work towards health outcomes, although it does consider access to sexual and reproductive health services (Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland n.d.). Anti-corruption is not mentioned in the strategy, although the independence of CSOs and the increasing voice of civil society are mentioned as a priority. Nonetheless, there is no specific reference to anti-corruption being a priority area.

Switzerland’s current development policy ended in 2024 (Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs 2020). Addressing corruption is considered under a sub-objective of good governance. No sector-specific approaches are considered. Switzerland’s health strategy and programming do not refer to the need to address corruption in the health sector.

The European Union’s engagement with anti-corruption in health is fragmented. ACTA principles are absent from its main health strategy but present as an important tenet in specific investment programmes. For instance, the EU’s Global Health Strategy does not call for the integration of anti-corruption measures; however, it vaguely mentions increasing transparency in health commodity markets and supply chains without detailing specific approaches (European Union 2022).

In contrast, the EU’s Global Gateway programme, which invests in development infrastructure, explicitly incorporates good governance and transparency as one of its six main operating principles (European Union 2021a). This principle applies directly to its health-related investments, such as strengthening medical supply chains and financing the infrastructure for vaccine and medicine manufacturing in Africa and Latin America. Here, anti-corruption is not the end goal itself but a method to ensure these large-scale investments are effective and well managed. This operational focus is complemented by high-level political acknowledgement; the EU Council has adopted conclusions recognising corruption as a barrier to development (European Council 2023) – a move influenced by Sweden’s presidency. However, this political recognition and the application of governance principles within specific programmes have not yet translated into a dedicated, overarching EU policy for integrating anti-corruption across its development efforts.

The lack of explicit strategic integration is reflected in the funding patterns of these development partners, which often show indirect or fragmented support for ACTA in health. Denmark’s IATI data are initially surprising. Its activities marked as health and corruption are the largest of all development partners, at 277.4 million euros. However, this figure is composed of core funding disbursements to UN agencies like the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and UN Women. Denmark’s strategies for engagement with these bodies do contain objectives on tackling corruption (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark n.d). Yet, the interviews confirmed that the primary intention of these specific objectives is to establish fiduciary safeguards – ensuring UN agencies mitigate losses when using Danish funds – rather than to mandate that the agencies undertake programmatic anti-corruption work themselves.

Finland’s indirect strategic approach is reflected in its IATI data. Its recorded investment is comparatively modest, totalling approximately 4.2 million euros across at least 17 activities. The funding is not directed at dedicated ACTA in health programmes but is instead channelled through a mix of mechanisms. This includes core funding to multilateral bodies like the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC); contributions to multi-development partner initiatives like the World Bank’s Nordic Trust Fund; and smaller grants to civil society for projects where ACTA in health is a component of a broader goal. This funding pattern aligns with Finland’s strategic priority of strengthening civil society rather than engaging in direct, sectoral anti-corruption interventions.

This is also reflected in Switzerland’s IATI funding data, which show an investment of approximately 46 million euros in activities linking ACTA and health. This funding follows two distinct channels. The vast majority is channelled through multilateral partners like the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) for broad ‘strengthened local governance’ programmes, where anti-corruption is an integrated component. The second channel involves direct support to civil society, such as multiple grants to Transparency International Bangladesh. This dual approach shows that while Switzerland lacks a dedicated ACTA in health strategy, it addresses the issue by funding governance-focused CSOs and integrating anti-corruption elements into its large multilateral contributions.

Common trends and differences among the three approaches

A clear pattern emerges from our analysis: a development partner’s official strategy is the single most important factor determining its capacity and willingness to act on health sector corruption. Without a formal strategy integrating ACTA into health, the issue is consistently sidelined.

A comparative reflection across the three development partner categories reveals a direct link between a development partner’s official strategic approach and its internal capacity for action. For development partners with fully integrated approaches (Category 1), the strategic mandate fosters closer collaboration between their internal health and anti-corruption units. As seen with Norway, Sweden, and the US, this internal alignment is a major success factor, enabling more effective, collective action on the international stage. In contrast, for development partners who consider anti-corruption a priority but do not integrate it sectorally (Category 2), or those with no explicit strategic focus (Category 3), this internal synergy is far less apparent. Their health and governance teams often operate in parallel, without a clear strategic directive, and collaboration on ACTA in health remains ad hoc rather than systemic.

The lack of integration of ACTA into health strategies poses a barrier to advancing work and investment on the topic. Without strategic prioritisation, the topic does not receive the necessary attention, while the internal structures needed to support it remain undeveloped. This effectively silos the issue within governance departments, relieving health teams of direct responsibility. As interviewees noted, health programmes are designed to meet specific health outcomes. Without a strategic mandate to include ACTA, it is perceived as an unfunded or secondary objective.

Nonetheless, even where there was a strategy explicitly integrating anti-corruption into the health sector, significant barriers limit the translation of high-level policy into consistent action at the country level.

iii. Most multilateral agencies and IFIs engage with anti-corruption and health less strategically

This report reviewed the strategies of major global health initiatives, along with those of multilateral agencies and IFIs working in the health sector. The analysis found low levels of integration of ACTA into health. Exceptions were the WHO and IADB, which have explicit reference within strategy documents to mainstreaming ACTA into the sector. Nine global health initiatives, multilateral agencies, and IFIs were considered as part of the review.

Our reviews found that IFIs do not have overarching development strategies – potentially due to the breadth of work and the number of partners that they engage with. UN agencies and global health initiatives did have overarching development strategies, and these were reviewed. Additionally, our analysis of IATI data found that records for UN agencies, IFIs, and global health initiatives were incomplete. Subsequently we could not make a full analysis of activities by these institutions.

Despite the lack of strategic integration, evidence shows that agencies did – albeit inconsistently – engage in activities to counter corruption. GFATM and GAVI have invested in mechanisms to safeguard against corruption and misuse of their funds. The World Bank, meanwhile, has worked with governments to invest in reforms that counter corruption in the health sector, including support to PFM reforms and procurement systems strengthening. The interviews revealed that anti-corruption approaches by UN agencies were more likely to be technical in nature. This recognised the UN’s role in supporting its member states to attain their development aims independently.

The analysis uncovered three distinct approaches: a small group that explicitly integrates ACTA into health work; a group that works towards accountability and fiduciary safeguards; and a large group that prioritises health but lacks an explicit ACTA focus (see Table 3).

Table 3: Multilateral institutions’ approach to ACTA in health

|

Institution |

Approach category |

Has a single overarching strategy? |

|

Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) |

Explicit integration |

No |

|

World Health Organization (WHO) |

Explicit integration |

Yes |

|

GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance |

Accountability and fiduciary safeguards |

Yes |

|

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria (GFATM) |

Accountability and fiduciary safeguards |

Yes |

|

African Development Bank (AfDB) |

Health priority without explicit ACTA |

No |

|

Asian Development Bank (ADB) |

Health priority without explicit ACTA |

No |

|

UNICEF |

Health priority without explicit ACTA |

Yes |

|

UN Population Fund (UNFPA) |

Health priority without explicit ACTA |

Yes |

|

The World Bank Group |

Health priority without explicit ACTA |

No |

Category 1: Explicit integration of ACTA into health strategies

Only two institutions, the IADB and the WHO, have strategies that explicitly and comprehensively integrate ACTA into their health sector work. However, their approaches reflect different mandates.

The IADB Health Sector Framework is the most comprehensive (IADB 2021). The IADB recognises that corruption and waste contribute to low productivity and sub-optimal quality of health services. It also recognises that corruption poses a challenge to the attainment of universal health coverage (UHC), and that the sector is highly vulnerable to corruption. This is a result of: (i) the amounts of money involved; (ii) the large number of dispersed actors making decisions that require judgement and discretion; and (iii) uncertainties and informational constraints that make it difficult to determine whether corruption occurred. In response, the IADB looks to improve the governance of health systems, ensuring they are led by the public sector and are accountable both for their performance and to the citizens they serve.

The WHO’s programme of work also briefly mentions ACTA. Specifically, the WHO aims to ensure that medicines procurement and supply chains are free from corruption. It also references the importance of data transparency to foster trust in health systems. Looking ahead, addressing corruption is included in their draft 2025–2028 programme of work (WHO 2024a) as an outcome of strengthening primary care approaches. The WHO is planning initiatives to expand the scope and capacity of health governance to address corruption in health systems and to promote social participation.

Category 2: Work towards accountability and fiduciary safeguards

A second group of institutions, primarily the global health initiatives, frame their engagement around ‘accountability’ and risk management. This is driven by a need to safeguard funds rather than a broad anti-corruption agenda.

The GFATM’s strategy includes several references to supporting efforts to increase the accountability of health systems and services. This includes support for the development of community accountability measures, supporting health governance frameworks, and establishing accountability mechanisms within product supply chains. However, corruption is not referred to within the strategy (GFATM 2021).

Similarly, GAVI’s strategy does not refer to ACTA (GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance n.d.). Equity is one of the four goals of the strategy, which could be a potential entry point. Despite the lack of strategic focus, GAVI’s latest risk and assurance report flags downstream corruption and theft of funds as a major risk area for operational success (GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, 2023)

Category 3: Health as a priority without explicit ACTA integration

The largest group of multilateral institutions and financing banks prioritise health but do not explicitly integrate anti-corruption into their strategies. Instead, they often use broader, more politically neutral terms like ‘governance’, ‘accountability’, and ‘efficiency’.

Among the IFIs, the World Bank’s approach to health mainly involves supporting countries to achieve UHC. The Bank does not appear to have a singular comprehensive health strategy, and there is only one position paper (which centres on emergency responses) that recognises the role of transparency and accountability in health. The AfDB also lacks an overarching health strategy (AfDB 2021), and its Strategy for Quality Health Infrastructure makes no reference to any of the components of ACTA. The Asian Development Bank’s Health Sector Directional Guide makes no mention of tackling corruption (ADB 2022). However, it does state that the ADB plans to work to improve health sector governance and will support efforts to enhance accountability towards citizens as part of its governance support.

This pattern is also seen in many UN agencies. Neither UNICEF nor UNFPAstrategies mention corruption (UNICEF 2016, UNFPA 2021), although both refer to supporting the development of accountability measures to improve service provision and promote community empowerment. This common approachsuggests thatthese organisations address ACTA-related issues implicitly through technical support for systems strengthening, rather than as a direct, standalone objective.

iv. When multilateral agencies and IFIs engage in ACTA, they tend to place stronger emphasis on preventing corruption in the use of funding

The interviews revealed that most agencies have well-established systems for mitigating financial risk in the disbursement of their funds. This is primarily achieved through a common strategy: using various external or ring-fenced mechanisms to oversee grant management and bypass perceived weaknesses in national systems. The specific tactics include:

Appointing independent monitors: GFATM and GAVI, for example, employ local fund agents to independently oversee grant management and implementation.

Requiring dedicated management units: In some contexts, the World Bank, GAVI, and the GFATM require governments to establish dedicated Project Management Units to implement funded projects, isolating them from broader systemic risks.

Channelling funds through trusted intermediaries: This is a common tactic, especially in high-risk environments where an agency like UNDP may act as the principal recipient. GAVI, for instance, channels up to two-thirds of its country grants through UNICEF and WHO. This leverages their established presence and robust UN audit processes to ensure oversight and accountability. Respondents cited the role of board members (primarily Sweden and Norway, who have sat on boards as funders of global health initiatives) as having been instrumental in increasing institutional safeguards against fund mismanagement. They also referred to the strengthening of the role of the Office of the Inspector General at the GFATM as one of the outcomes of bilateral development partners playing a role on the board. Respondents stated that agencies’ boards and committees have a strategic role to play to ensure that there is more work towards ACTA in health programmatic work. Such approaches are likely to be more successful if proposed or supported by multiple board members. It was also noted that the continued presence of the topic on agendas was a factor in bringing about change; one-off interventions were less likely to do so.

v. Recognising the barriers preventing action

Several challenges hinder the effective integration of anti-corruption into health work, even when it is strategically incorporated into bilateral and multilateral agencies’ plans.

One issue is that most work on anti-corruption is driven by headquarters, not country missions. According to several informants from bilateral agencies, headquarters personnel often see ACTA as a higher priority than their colleagues working locally, who are more concerned with immediate operational demands. At the same time, country missions may lack the necessary knowledge, capacity, and autonomy to act on the topic.

‘We were surprised at the lack of knowledge amongst our colleagues on our agency’s own anti-corruption measures. Colleagues were not aware of our own internal corruption reporting measures, and had limited knowledge of what could potentially constitute corruption in their day-to-day work.’

Key informant, bilateral development partner representative

Headquarters personnel, meanwhile, seldom have much influence on the design of programmes, which are often initiated by government partners. Key informants reported that recipient governments rarely requested support specifically for anti-corruption in the health sector. The principle of national ownership, which is central to the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, requires development partners to align support with partner government priorities (OECD 2005). So if the assistance is not explicitly requested, it cannot be easily prioritised in development partner support.

Key informants also explained that missions usually lack the autonomy to commission projects and programmes to further anti-corruption interventions at the community level. This aligns with the IATI data, which show a few country-level projects. This suggests that ACTA is more likely a byproduct of programming, unless there are specific concerns or significant political prioritisation of the issue.

Overall, work by colleagues in country missions was driven more by country needs and requests of partner governments, rather than their own strategies. In many cases, it was felt that development partner strategies served as frameworks or guidelines for work. Some respondents also reported that colleagues in missions felt there was often a disconnect between strategies and the reality of the requirements of partners, with strategies being viewed as documents written to serve the needs of their own politicians at home.

The second challenge relates to the existing evidence. Corruption is all too often perceived as a governance issue, rather than a health issue. Anti-corruption is generally not included due to a lack of evidence on the impact of accountability and transparency on health outcomes. This was particularly the case where there were competing demands for support. Key informants noted that the post-Covid economic climate has strained both development and domestic financing. With limited resources, there is more work towards improving system efficiencies and ensuring that health systems deliver value for money. Mitigating fraud and corruption risks plays an important role here; however, it is often not an explicit aim of support.

‘A lack of data often makes it difficult to push for anti-corruption to be prioritised; whilst we know that corruption is an issue, a lack of robust evidence on the scale of the issue, and lack of evidence-based solutions make prioritising anti-corruption difficult.’

Key informant, bilateral development partner representative

Additionally, interviewees from bilateral agencies also revealed a strong sense of political caution. They mentioned facing increasing domestic pressure on development assistance budgets. They expressed a clear concern that openly funding ‘anti-corruption’ projects could be framed negatively by the media or political opponents, fuelling arguments that development assistance money is being misused and should be cut.

Similarly, a central theme from interviews with multilateral staff was the imperative to remain politically neutral. As one official explained, their mandate is to be a technical partner – not a political actor. Consequently, they are often reluctant to use the term ‘corruption’ explicitly, as it can be perceived as ‘labelling’ or interfering in a country’s sensitive domestic affairs. Instead, multilateral agencies’ ACTA interventions tend to be technical in nature. They are directed towards addressing specific identified issues, such as procurement systems strengthening, PFM reforms, or supporting data management systems. These activities can increase transparency and safeguard against corruption. ACTA interventions tend not to be promoted as ‘anti-corruption’ or accountability but are presented as part of a broader set of interventions that work towards improving efficiency and effectiveness, which are more politically salient than corruption.

Questions on the amount of money being spent by governments on development assistance are also increasing across Europe and North America, with governments under added pressure to justify expenditure (Kinkartz 2025; Käppeli and Calleja 2022). Corruption is a politically sensitive topic. While development partners may have more flexibility as they can ground their engagement in their own government’s stated foreign policy commitments on anti-corruption, they still need to strike a balance between addressing legitimate concerns about the risks of corruption and supporting efforts to strengthen health systems.

Lastly, several respondents raised issues of transparency and accountability of UN agencies, many of which receive bilateral development partner funding to support anti-corruption and health initiatives (as is the case with Denmark and Switzerland – see ‘Category 3: Development partners with no explicit strategic focus on either health or ACTA’ above). Respondents felt that the UN system did not always do enough to respond to internal allegations of corruption within the system itself. Respondents considered that this constrained the ability of the UN system to be an effective vehicle to champion reforms within health systems.

vi. Opportunities for improvement and progression

Despite the barriers at the country level, interviewees from bilateral agencies pointed to a promising strategy for making progress: closer integration and collaboration between their internal health and anti-corruption teams. Respondents cited this internal alignment as a major success factor. It enables more effective collective action on the international stage – in turn creating opportunities for cooperation with multilateral partners. Such collaboration can lead to progress in terms of:

- Influencing multilateral strategies – such as integrating text on corruption into the WHO’s 2019–2013 programme of work (WHO 2019) and draft programme of work for 2025–2028 (WHO 2024a).

- Sustaining top-down pressure – through maintaining the topic on the agenda at board meetings of important global health institutions, eg at the GFATM and World Bank meetings. This serves both to ensure the agencies maintain strong compliance measures and to strengthen their institutional prioritisation of ACTA in health programming.

- Building partnerships– that is, fostering collaboration with multilateral agencies on the topic. There was recognition that IFIs see the Nordic states as important partners on anti-corruption and governance more broadly. This creates an opening for bilateral development partners to support IFIs in furthering the agenda.

Faced with the political sensitivities of direct government engagement, development partners who treat anti-corruption and health as separate development priorities appear to adopt a pragmatic twin-track approach. The first track involves top-down, institutional pressure, engaging with global bodies to improve anti-corruption safeguards in the health sector. Their goal is to push for institutional change while maintaining political distance. Examples of this include supporting the development of the audit and investigation function of GAVI, and participating in the audit and financing committee, as well as supporting the role of the Global Fund’s Office of the Inspector General (GFATM n.d.-a).

The second track works towards improving accountability at the local level by directly funding CSOs. For example, the UK has funded TI’s work on open contracting in health, while Canada has funded its work on inclusive service delivery in Africa. This approach empowers local actors to monitor services and demand accountability from the community level upwards. This creates domestic pressure for reform that complements the institutional pressure from above.

Additionally, interviewees expressed that it is important to approach corruption as a global issue, not one solely concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). As such, many are seeking to mitigate the role of their own nation, and other high-income countries, as enablers and facilitators of transnational corruption. This also takes place within the health sector, where issues of corruption are not always contained within geographical boundaries. For instance, global health supply chains face significant corruption risks due to their transnational nature, with pharmaceutical drugs relying on ingredients from multiple countries, and being processed and packaged across different locations before reaching their final destination (Kohler and Dimancesco 2020; OECD 2024a).

To bring corruption onto the agenda, more needs to be done to build understanding of the impacts of corruption on health outcomes. Even where development partners lack strategic prioritisation, support for more interventions to understand the links between corruption and health outcomes will help make the case for corruption to be brought onto the agenda in partner countries. Similarly, development partners may also consider bringing national and local anti-corruption organisations into discussions on health sector support. They can commission research into the impacts of corruption where none exists.

Greater use of political economy assessments may assist in identifying opportunities for intervention. Application of an anti-corruption lens to proposed reforms – for instance, financing reforms – can assist in identifying opportunities for greater engagement. Doing so will help raise prominence of the issue at the national level, bringing the topic onto the agenda, and will create legitimacy for UN agencies funded by them to engage on the topic within countries.

The UN system is accountable to member states; while it is members – rather than UN agencies – who are responsible for setting out the strategic direction of the UN. Informants from multilateral agencies, global health programmes, and IFIs also noted that their strategies are designed to achieve targets set at high-level meetings. They argued that it will be difficult to maintain momentum on ACTA without sustained high-level interest and commitments to anti-corruption from these forums. Therefore, there is an ongoing opportunity for governments and bilateral development partners to continue to ensure that ACTA is maintained on the global agenda.

For instance, member states should ensure progress is made on the 2023 UN High-Level Political Declaration on Universal Health Coverage before the next high-level meeting (United Nations General Assembly 2023). They can also put ACTA on the agenda at similar meetings and events on global health, such as the annual World Health Assembly (WHO n.d.). Other opportunities include the Lusaka Agenda agreements, which investigate strengthening financing for UHC (WHO 2024b). Differing approaches have been used to build wording on ACTA into agreements and documents. For instance, in the run-up to the 2023 High-Level Resolution on UHC, several bilateral development partners worked with members of the GNACTA working group to draft text on corruption in health that was then proposed by development partner governments.

Lastly, for global health partnership initiatives like GAVI and the GFATM, respondents stated that the primary channel for influence is through their boards. These boards comprise multiple stakeholders, including representatives from development partner and recipient governments, civil society, and the private sector. They argued that the most effective way for development partners to shape strategies is to consistently keep ACTA on a board’s agenda.

Key informants repeatedly highlighted Norway’s work as a useful example. By consistently using its GFATM board seat and collaborating with other partners, Norway was influential in pushing for stronger risk management across organisations. This secured investment in systems to mitigate financial losses, and strengthened the oversight capacity of the GFATM’s Office of the Inspector General. Similarly, key informants noted that Sweden successfully proposed anti-corruption text for the European Union’s collective statement at the World Health Assembly. This was achieved by first building consensus among fellow EU member states. This demonstrates how presenting a unified position can be more impactful than a single country acting alone. Such reforms have been cited as having been effective in furthering reforms, and development partners might like to consider similar approaches to UN bodies.

3. Country case studies

Bangladesh was selected at the outset of this work in March 2024. The then Awami League Government in Bangladesh had not prioritised anti-corruption. This was despite long-standing concerns on the impact of corruption, and poor rankings in the Corruption Perceptions Index (Transparency International 2024). In contrast, Zambia was chosen in part because the current President Hakinde Hichilema came to power in 2021, having campaigned against corruption (Reddy 2024). By presenting these two distinct scenarios, the aim is to illustrate how the political will of a host country can shape the space for engagement, the choice of partners, and the types of anti-corruption initiatives that development partners and multilateral agencies pursue.

i. Bangladesh

Corruption is a well-documented and pervasive problem within Bangladesh’s health sector (McDevitt 2015; Naher et al. 2018; SOAS-ACE n.d.-b). Its impact is felt across the health system and it affects: pharmaceutical development and procurement (SOAS-ACE n.d.-a); medical training and recruitment (Tithi 2023); general procurement practices (Hossain et al. 2023); and access to services (McDevitt 2015; Naher et al. 2018).

Despite the government claiming it is a priority, there has been little progress in addressing corruption. Under the Awami League Government, led by Sheikh Hasina, there was low political prioritisation of anti-corruption. Critics argued that accountability bodies (including the Anti-Corruption Commission) were systematically weakened, dependent on politicised state institutions, and lacked the independence to prosecute powerful, politically connected individuals (Transparency International Bangladesh 2024). Despite economic progress, this led to increasing public discontent over high levels of corruption (Ethirajan and Ritchie 2024). This discontent became a central grievance that fuelled the mass student-led protests in mid-2024. This ultimately led to the resignation of the Prime Minister (Dhillon et al. 2024).

We reviewed country cooperation strategies and frameworks for Bangladesh from the Asian Development Bank (ADB 2021), the United Nations (United Nations Bangladesh 2021), the World Bank (World Bank 2023a), and the WHO (WHO 2022) (see Table 4).

Table 4: Review of health and governance priorities in multilateral country cooperation strategies for Bangladesh

|

Institution |

Strategy date |

Is health a strategic priority? |

Is corruption referenced? |

Is governance strengthening referenced?

|

Is PFM strengthening referenced? |

|

ADB |

2021 |

X |

X |

|

|

|

United Nations |

2021 |

X |

|

X |

|

|

World Bank |

2023 |

X |

|

|

X |

|

WHO |

2022 |

X |

|

|

|

All agencies considered health to be a priority area in their country cooperation strategies. Nonetheless, they put limited priority on corruption as a major development challenge.

While the World Bank’s Bangladesh country partnership framework does recognise the need to strengthen PFM and procurement systems across sectors (both of which can mitigate corruption risks), it does not refer to planned interventions to support ACTA in the health sector (World Bank 2023a). Likewise, ACTA in the health sector is not discussed as a topic in the Asian Development Bank (ADB 2021) and WHO country partnership strategies. In the case of the WHO, however, the strategy does outline three deliverables that could provide opportunities to work on ACTA issues (WHO 2022):

- Developing an evidence-based health financing model: This can link into transparency in health financing, as civic input using transparent financial data provides a richer evidence base for policy decisions.

- Enhancing national capacity on the quality, safety, and efficacy of medical products: This reduces the ability of unscrupulous actors to cut corners in the production of drugs or to insert poor-quality drugs into the supply chain via bribes.

- Strengthening the digital health system: Widespread use of electronic datasets allows for more effective transparency provisions from public entities.

In the case of the UN system, the UN Bangladesh country cooperation framework looks to support ‘strengthened and more coordinated, inclusive and accountable governance system at the national and local levels’ (United Nations Bangladesh 2021, p. 23). It also aims to support the functioning of national anti-corruption bodies and systems. Nonetheless, ACTA in health is not specifically mentioned as a priority in the framework. Barriers to accessing services, such as corruption, are not discussed.

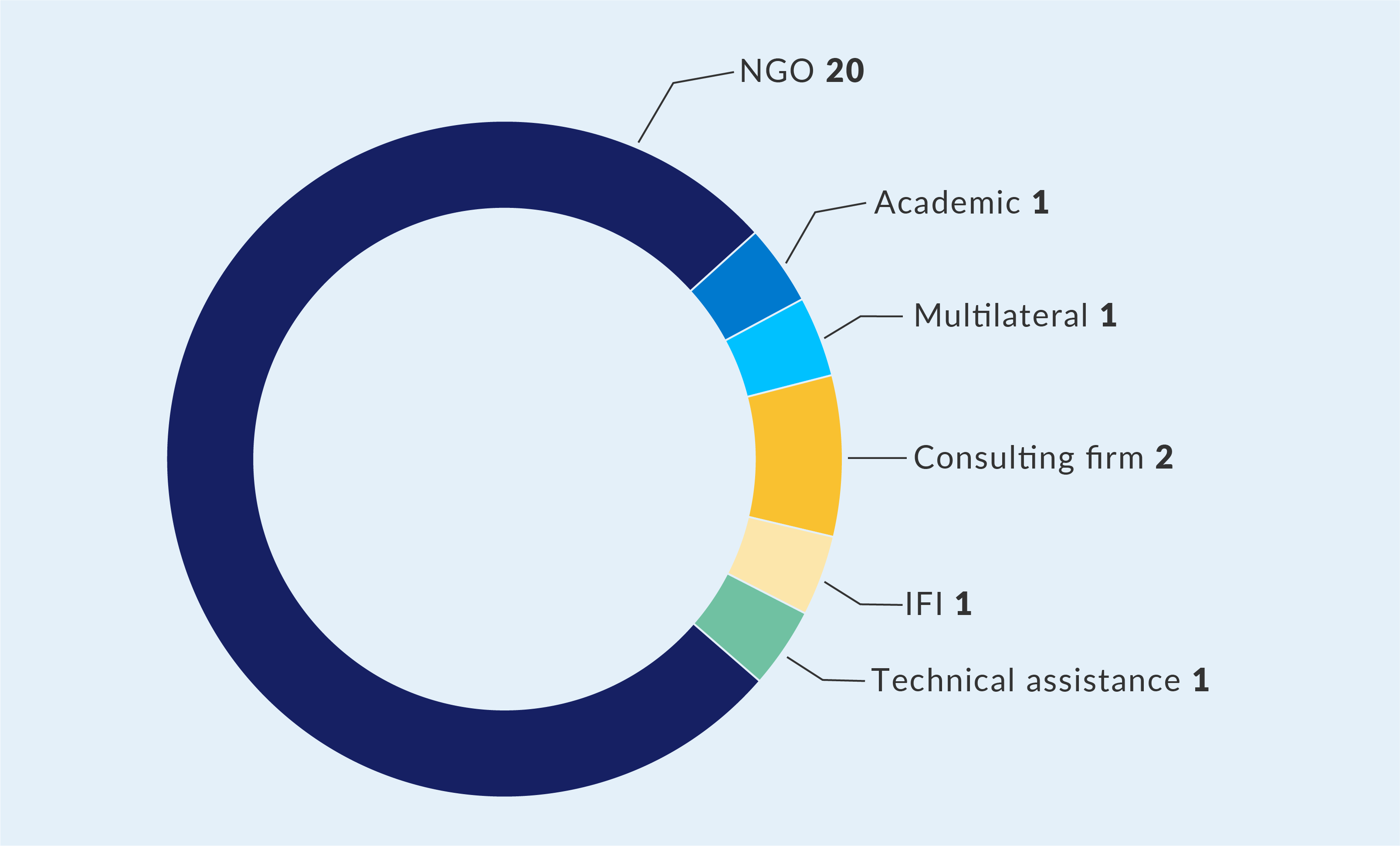

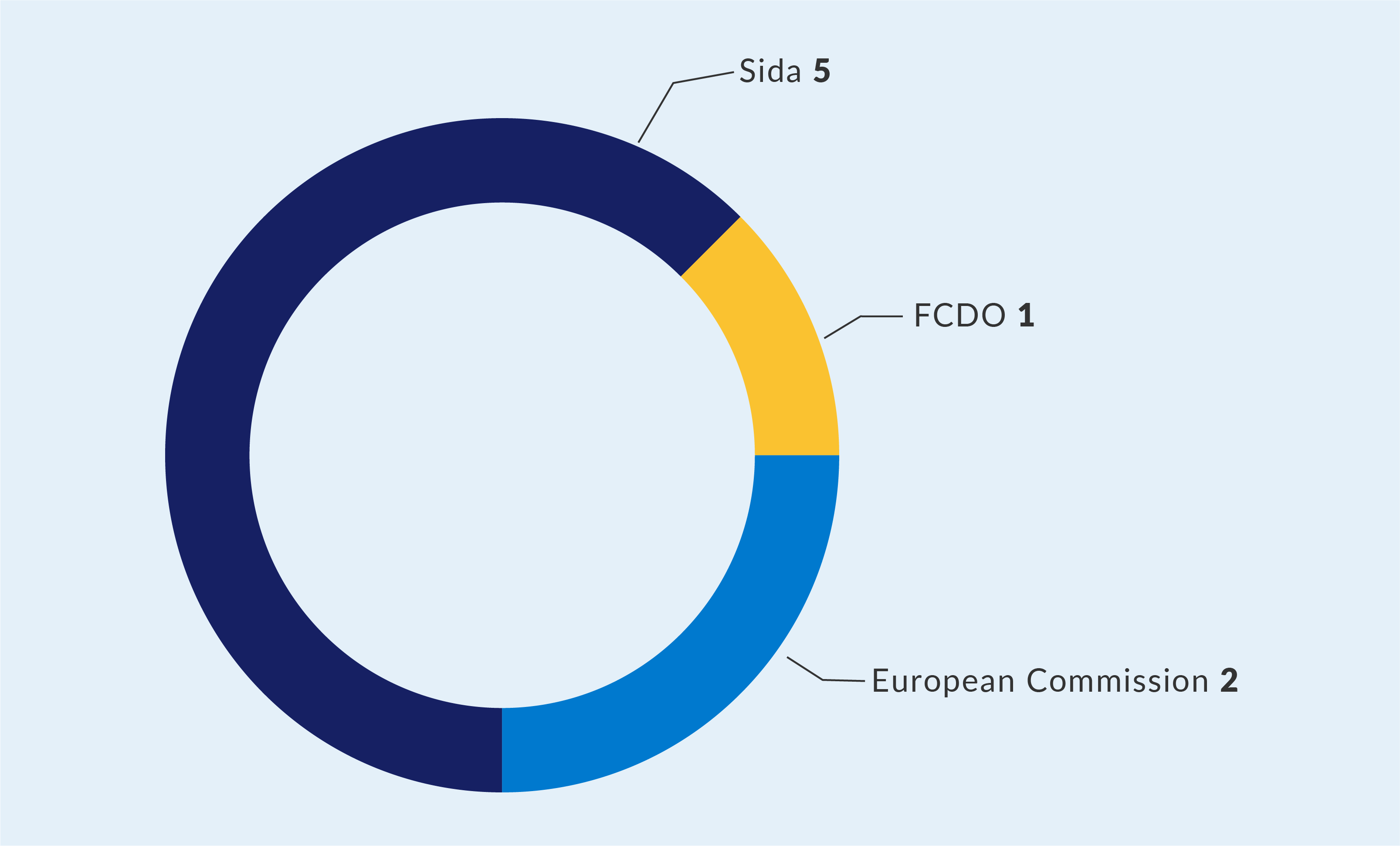

A review of IATI data found Sweden and Switzerland to be the two largest funders of anti-corruption programmes in Bangladesh. According to IATI data, 26 activities referred to corruption and health, and 22 of those were funded by Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and Sida. Many activities (20 in total, see Figure 3) provided support to Bangladeshi non-governmental organisations (NGOs) for work on corruption, accountability, and health. No interventions in the IATI dataset appeared to provide direct support to the Government of Bangladesh or public bodies on issues of ACTA in health.

Figure 3: IATI records for Bangladesh of projects containing references to health and corruption by recipient type

The results of IATI data coincide with the analysis of Sweden and Switzerland’s country cooperation strategies. Although both organisational strategies recognise the need to strengthen democratic accountability and address corruption in Bangladesh, neither mentions providing support directly to the Government of Bangladesh to address corruption (SDC 2022; Sida 2024). In the case of Sida, their approach references providing direct support to organisations working to tackle corruption. In the case of Switzerland, SDC explicitly states that it will provide support to CSOs and independent media to counter corruption and support participatory planning and decision-making (SDC 2022). Moreover, while Sida’s strategy prioritises the health sector, the agency does not appear to have a dedicated ACTA in health strategy for the country. This suggests there is no formal, integrated approach that requires anti-corruption measures to be systematically included in its health sector support.

Additionally, a review of the projects implemented by development partners in Bangladesh mirrors the constrained political environment. Rather than working towards addressing corruption directly, they instead support either broad technical reforms or targeted, evidence-based engagement with civil society and other actors. There is evidence of work undertaken by IFIs to support health systems to be more resilient to corruption under broader programmes aimed at improving PFM. For instance, the World Bank supported the development of a national government e-procurement platform (World Bank 2023b). This type of procurement system strengthening indirectly supports anti-corruption efforts by increasing transparency and allowing for greater oversight of transactions.

A more direct approach was taken by the governance and health teams at Sida Bangladesh, which brought together development partners and relevant CSOs working on anti-corruption. The coalition worked to identify areas where it could promote horizontal checks and balances across the health system, rather than relying on top-down approaches (SOAS-ACE 2024). One example included working with doctors to identify the reasons behind illegal absenteeism. Through these discussions, the coalition discovered that a large proportion of women doctors who were absent cited being away from their families as a reason. It then used this information to work with district health officials to improve working conditions – for example, by considering posting doctors closer to their families.

Nonetheless, there appears to have been relatively little investment overall by development partners and multilaterals to engage the Government of Bangladesh in tackling corruption in health. Interview respondents stated that it was almost impossible to engage with the government and public bodies on anti-corruption in the health space, as the topic was off-limits. Similarly, respondents were not aware of anti-corruption mainstreaming in health having been raised in bilateral government negotiations or discussions related to health sector support. This meant it was difficult to provide direct assistance to mitigate corruption.

This political barrier helps to explain why development partner approaches have emphasised indirect technical support or bottom-up coalitions. Under the previous administration, engaging indirectly by supporting PFM or civil society-led coalitions was the most realistic way forward. However, political situations are not static. The fall of the government in mid-2024 – driven by widespread anti-corruption protests – could fundamentally change this context. This development may present a critical, new window of opportunity for development partners to support more direct and systemic anti-corruption reforms in Bangladesh’s health sector.

ii. Zambia