Query

Please provide an overview of the use and effectiveness of custodial sentences for private individuals who have been found guilty of collusion and other cartel activity, with a focus on European Union countries.

Background

Competitive and fair markets provide consumers with better quality goods and services, lower prices and innovative products, while sustaining economic growth and innovation (OECD n.d.). Competition in procurement includes an open and transparent bidding process, open access to opportunities to a wide range of businesses, and an evaluation of bids that are selected on objective criteria such as price, quality and technical ability. These factors help to ensure that buyers select the bid that supplies the optimal balance of both benefits and cost (House of Commons 2023).

While fair competition is important for both the public and private sector, it is particularly pertinent in public procurement as it ensures that public funds are spent effectively. Public procurement is the process by which public authorities purchase work, goods or services from companies in sectors such as energy, transport, waste management, social protection and for the provision of health or education services (EU n.d.). This typically constitutes a significant portion of government spending; for example, in the European Union (EU) it accounts for roughly 14% of the EU’s gross domestic product (GDP) (European Commission 2022).

Despite the vast sums of money in public procurement, many countries still struggle to ensure that the system is effective, transparent and safe from fraud and other forms of illicit activities. For instance, the European Commission’s performance indicators measure whether states get good value for money through 12 key indicators. Several key indicators that may suggest fraud and misappropriation of public funds measured from ‘unsatisfactory performance’ to ‘average performance’ among EU member states. These include single bidder contracts and missing supplier registration, among others5cd03ef700e4 (European Commission 2022). The performance of these countries throughout the EU indicates that there is still significant scope for improving the effectiveness of public procurement, including reducing the risk of potential fraud and misappropriation of public funds.

The volume of transactions and the financial interests at stake, the complexity of the process and the close interaction between public officials and businesses makes public procurement particularly vulnerable to corruption (OECD 2016). The forms of corruption in public procurement include the bribery of public officials by private companies for favourable contracts, conflict of interest, embezzlement and the abuse of public office functions for private gain (UNDOC n.d.).

Another interrelated risk that undermines competition in public procurement is collusion between companies, which may or may not involve a public official. Collusion defined as a secret agreement and cooperation between interested parties for a purpose that is fraudulent, deceitful or illegal (Dowding n.d.). This can involve anti-competitive activities such as agreements to refrain from undercutting each other’s prices or selling in each other’s market areas (Dowding n.d.).

Collusive activities usually take place between a group of companies that are referred to as ‘cartels’ (García Rodríguez 2022). This involves the horizontal relationship between bidders (private companies), whereas corruption which – in this context – would typically involve a vertical relationship between bidders and public officials (OECD 2020a:24). Corruption often facilitates collusion as many cartels survive because the companies have an insider in the government procurement agency (Auriol, Hjelmeng and Søreide 2017).

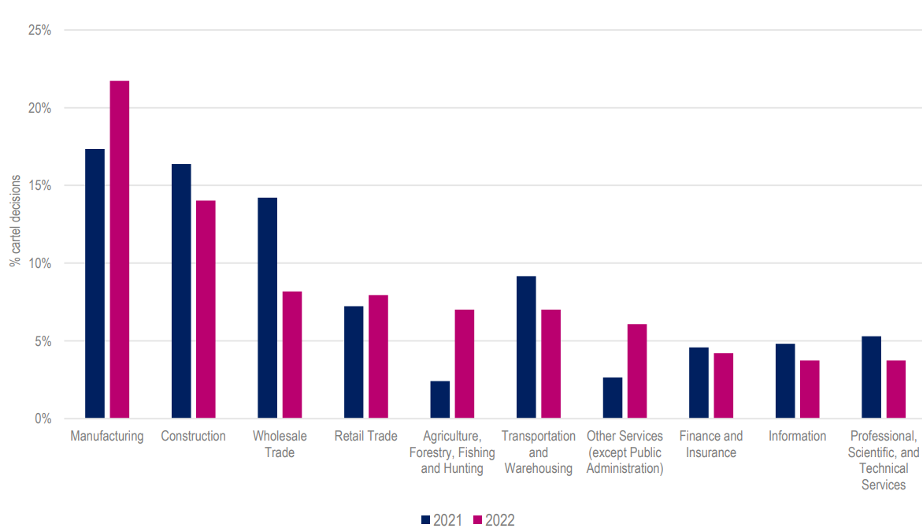

Empirical evidence on cartels prosecuted in Europe and the United States (US) between 1998 and 2009 suggest that cartels are typically organised by ‘small groups of employees’ that are active at various levels but all having the common power to take decisions on price, output and/or the decision on markets (OECD 2020a:18). Cartel activities impact several key sectors and industries, as illustrated in Figure 1 below, which shows the industries most affected by cartel activities between 2021 and 2022 based on 77 OECD and non-OECD jurisdictions:

Figure 1: Top-10 industries with judicial decisions on cartels in 2021 and 2022 as a percentage of all cartel decisions

Source: OECD 2024: 21

As illustrated by Figure 1, collusion affects key areas of public and private spending in manufacturing, construction, agriculture and others. This has devastating effects for public finances and consumers worldwide.

For example, in the US, the data shows that cartels on average overcharge purchasers by 30% (Connor and Lande 2005). Price hikes in drug pricing led to medicine such as antibiotics to increase in price between 2013 and 2014 from US$20 to US$1,849 for a bottle (Clark, Fabiili and Lasio 2022). An investigation into the drug pricing increase found that this was a result of companies that had conspired to fix prices and rig bids (Clark, Fabiola and Lasio 2022). In Chile, paper manufacturers fixed prices for at least a decade in the country’s tissue and toilet paper market, which contributed to widespread discontent and protests against inequality in the country caused by price rigging (Reuters 2020).

Penalties for corrupt behaviour by public officials regarding procurement contracts is generally seen as a fundamental element of anti-corruption prevention and enforcement. For example, the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) specifically mandates that each state party take steps to prevent corruption in public procurement and public finances more widely (UN 2004:12). Similarly, it is common practice that legal entities (private companies) are held criminally liable and fined in many jurisdictions, as well as other sanctions such as disqualification from public bids (OECD 2020a:7).

However, although there is international agreement on imposing criminal penalties for corruption, the situation is more complex when it comes to private individuals participating in collusion. There is currently no international consensus on the matter of custodial sentences against individuals convicted of collusion and other cartel activities (OECD 2020a). And, regarding convictions for financial crimes more broadly, custodial sentences are uncommon worldwide and rates of recidivism for financial crimes are estimated to be relatively high (Bell 2023; Huttunen et al. 2022:39). Given that the data indicates that there has been no reduction in the number of detected cartels worldwide, this has raised the question of whether the investigative and enforcement tools currently available are effective deterrents for collusion (OECD 2020a:5-6). Many now argue that stricter punishments, including custodial sentences, should be implemented to deter cartels and their members.

This Helpdesk Answer reviews the status, particularly within the EU and in public procurement, of countries that impose custodial sentences on private individuals for engaging in collusion. It then examines the evidence on whether custodial sentences provide an effective deterrent for collusion, a particularly pertinent question given that collusion is widespread globally and its consequences (undermining competition in procurement) have vast impacts on the economy and public finances. However, as the literature on the effectiveness of custodial sentences against collusion is not extensive, this Helpdesk Answer also draws on broader literature on their effectiveness against white-collar crime.c0fe0534fc22

Custodial sentences for collusion

Competition authorities are responsible for remedying anti-competitive conduct such as collusion (Trémolet and Binder 2009). However, the power of competition agencies in criminal investigations varies between jurisdictions; in some cases, their access to certain investigative powers and tools may be subject to the ‘qualification’ of the crime, otherwise other enforcement authorities typically step in (OECD 2020a:22-23). For colluding companies, the sanction imposed is either criminal or administrative and conviction typically results in a fine or debarment (Rosenberg and Exposto 2020:4).

For individuals, the sanctions imposed are through civil, administrative or criminal proceedings (OECD 20201:6). Criminal sanctions for private individuals can entail a fine and other non-custodial sanctions, such as barring individuals from serving as an officer of a public company, loss of business licences, community service and requirements to publish the violation (OECD 2020:7). Criminal sanctions can also entail custodial sentences in many countries. In their data collection on competition law violations, the OECD measured that, out of 55 jurisdictions surveyed, criminal sanctions on individuals were possible (as of 20203ee54526a9a6) in 26 jurisdictions (OECD 2020a:16).

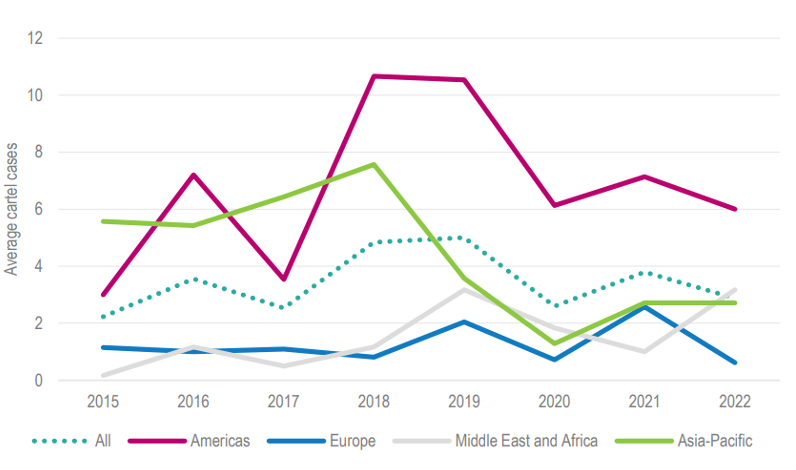

Figure 2 below shows that the average number of collusion and cartel cases in which fines on individuals were given ranges between 1 and just over 10 per year throughout each region (Americas, Europe, Middle East and Africa, and Asia-Pacific). The global average tends to fluctuate between 2 and 5 cartel cases resulting in fines per year:

Figure 2: Average number of cartel cases in which fines on individuals were imposed by the competition authority or by a court (excluding appeals), by region, 2015-22:

Source: OECD 2024:31

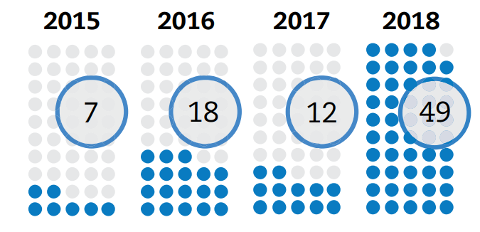

While fines are the more common criminal sanction imposed on individuals, the number of custodial sentences handed out for cartel activity is starting to increase globally. The data shows that the number of cartel cases for which a prison sentence was imposed, often with other sanctions, increased from 7 cases in 2015 to 49 in 2018 (measured from 55 jurisdictions):

Figure 3: Number of cartel cases for which prison sentences were imposed, 2015-2018

Source: OECD 2020b:62

While the application of custodial sentences for individuals is not yet widespread, this data does indicate a growing trend (OECD 2020b:61). However, even in jurisdictions where these are applied, the actual use of custodial sanctions is limited. In four cartel cases in Ireland, 18 individuals received criminal convictions but most of them received only suspended jail time and fines (OECD 2020a:17). In the UK, custodial sentences were given in only 2 cases until 2020 through guilty pleas (OECD 2020a:17).

An important consideration in effectively sanctioning individuals for collusion is harmonisation between different jurisdictions. A criminal may, for example, violate the anti-trust laws of one country where custodial sentences exist and then flee to a country that is more lenient (Boskovic 2014:7). Therefore, some argue that the effectiveness of custodial sentences in one jurisdiction also relies on its existence in other jurisdictions or extradition treaties. Furthermore, cartels themselves often collude in and across multiple jurisdictions (OECD 2020a:36).

The state of play in the European Union

While the US has had criminal and custodial sentences for collusion and cartel activities for over a century and the UK for a decade, EU countries have lagged behind (Agrawal 2023). This is primarily since, given the EU’s political structure, it is difficult to propose a one-fits-all criminal enforcement system (Agrawal 2023).

Nonetheless, the European Commission does provide some guidance to member states on protecting competition in public procurement. Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) refers to the rules of competition, which state practices that are prohibited and incompatible with the internal EU market such as: directly or indirectly fixing purchasing or selling prices; limiting or controlling production, markets, technical development; sharing markets or sources of supply; applying dissimilar conditions to equivalent transactions with other trading parties thereby placing them at a competitive disadvantage; and making the conclusion of contracts subject to acceptance by other parties.

The European Commission can impose fines for infringement of Article 101 of the TFEU (European Commission n.d.). The amount of these fines depends on the gravity and duration of the infringement and the fine must not exceed 10% of the total turnover generated by the business year preceding the decision (European Commission n.d.). However, criminal penalties are stipulated under each member state’s national legislation. The following section examines legislative provisions adopted by several EU member states that have introduced custodial sentences for collusion and other cartel activities.5884d14bb587

Jurisdictions for custodial sentences for collusion or offences related to collusionb2aa403f43b4

Austria

The Austrian Federal Cartel Act covers cartels and collusion and imposes civil penalties such as fines. If collusion is accompanied by other criminal acts such as fraud, bribery and conspiracy, then the penal code is applied. For fraud, for example, Section 146 sets out that if a person commits fraud with the intention to gain unlawful benefit for themselves or another person, then the potential punishment is imprisonment up to six months or a monetary fine (Knoetzl 2018).

Denmark

In Denmark, under the competition act, individuals who grossly violate competition laws can be fined or imprisoned for up to one year and six months. Under particularly aggravating circumstances this can be increased to up to nine years (Antitrust Alliance 2019).

Estonia

Section 400 of the Estonian penal code sets out the offences related to competition, specifically on ‘agreements, decisions and concerted practices prejudicing free competition’. These are punishable by a fine or imprisonment for up to one year, if public procurement contracts are involved, then one to three years’ imprisonment.

France

The French commercial code sets out in Article L420-1 that cartel activities such as limiting access to the market or the free exercise of competition, price fixing, limiting control of production and sharing out the markets or sources of supplies. Private persons can be punished for these offences with a prison sentence of up to four years and a fine of €75,000.

Germany

The German criminal code section 298 refers to collusive tendering. It specifies that ‘whoever, in connection with an invitation to tender relating to goods or services, makes an offer based on an unlawful agreement whose purpose is to cause the organiser to accept a specific offer incurs a penalty of imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years or a fine’.

Greece

Article 44 of the protection of free competition law states that any person who executes an agreement, takes a decision or applied a concerted practice under the prohibited collusion activities (defined in Article 1) shall be punished by a fine between €15,000 and €1 million. Alternatively, a term of imprisonment of at least two years can be imposed.

Hungary

Act C Section 420 of the criminal code stipulates that any person who enters into an agreement aiming to manipulate the outcome of an open or restricted procedure held in connection with a public procurement procedure or an activity that is subject to a concession contract by fixing prices can be punished by imprisonment of between one to five years.

Ireland

The Irish competition act refers to cartel activity such as directly or indirectly fixing purchase or selling prices, limiting or controlling production, sharing markers or sources of supply, or any other behaviours undermining competition. The penalties include fines for individuals of up to €4 million or up to five years’ imprisonment.

Norway

Section 32 of the Norwegian competition act states that those found guilty of cartel activities are faced with fines or imprisonment of up to three years. Under particularly aggravating circumstances, this can be extended to up to six years’ imprisonment.

Poland

Under the Polish competition law, private persons can face fines of up to €5 million for infringing anti-trust laws, and in cases of bid-rigging, there can be criminal charges with the possibility of imprisonment up to three years (Aziewicz 2022).

Romania

The Romanian competition law provides sanctions of a fine of up to 10% of the global turnover of the company that was registered in the year before, and any employees that were directly involved in bid-rigging can face sanctions with imprisonment from six months to five years (CMS 2023).

Spain

Article 262 of the Spanish criminal code states that those who make arrangements among themselves to alter the final bid in a public tender or auction may face imprisonment from one to three years.

The effectiveness of custodial sentences

Penalties can have multiple purposes: specific deterrence (the individual), general deterrence (the wider public), incapacitation, rehabilitation, retribution and restitution (LibreTexts n.d.). Regarding the rationale to justify criminal sanctions for collusion and cartels, and custodial sentences in particular, several theories are most commonly held in the debate: retribution, reassurance and retribution, rehabilitation and deterrence theories.

The first, the retribution theory, does not justify criminal sanctions with the potential deterrent effect on future crimes, but rather that criminal punishment is justified by the fact that the individual engaged in a prohibited or morally wrong conduct (UNODC 2020:8-9). Therefore, for cartels that subvert the competitive process, which is fundamental to a market economy system, they should be sanctioned for subverting moral wrongs caused by their stealing, deception and cheating (UNODC 2020:8-9). There is an argument that imposing fines on cartel offenders is unlikely to adequately compensate for the damage they may have caused. For example, the damages caused by cartels is not limited to inflated prices (which could be remedied through private lawsuits and claims for damages) but also extends to a loss in wider economic efficiency (OECD 2020a:8). Therefore, the size of fines needed to be imposed on companies in response to these impacts would be too large for the company to survive (OECD 2020a:8).

In the second theory, criminal penalties also act as public reassurance that laws and policies are enacted to ‘send a message’ and assure the public that their views and concerns have been noted (Tonry 2006:38-39). In this sense, legislators adopt symbolic policies meant primarily to acknowledge public anxiety (Tonry 2006:38). It is argued by some (Garland 2001 cited in Tonry 2006) that many crime control policies have been adopted for these ‘expressive’ reasons, not because policymakers believe that they would reduce crime rates but because they wanted to reassure an anxious public concerned about rising crime rates. There is a discourse in the literature over whether the fact that white-collar criminals are less likely to face prison sentences for their crimes than people convicted of blue-collar crime (such as drug possession) is evidence of a ‘class bias’ in favour of the former at the expense of the latter (Eitle 2020). In this sense, custodial sentences against individuals convicted of collusion could act as a reassurance for the public that crime is not addressed in a way they may perceive as inconsistent.

Rehabilitation aims to prevent future crime through altering the defendant’s behaviour and can include educational programmes and counselling often in conjunction with other penalties such as incarceration (LibreTexts n.d.). Rehabilitation is considered important as its aim is to infuse empathy in offenders and turn them into productive members of society, with interventions that intend to force the offenders to see the damage the caused to victims and wider society (Luedtke 2014:324-325). Evidence from interviews with white collar defendants in Malaysia suggest that rehabilitative programmes for inmates that focused on behavioural correction, psychological and emotional development and vocational training were beneficial and helped the interviewees with re-employment and reintegration after release (Yeok et al. 2020).

The final theory is the deterrence theory under which a sanction against criminal conduct can be justified if it prevents or reduces future crime (OECD 2020a:8). Several voices in the literature argue that fines act as a sufficient deterrent against cartels. For example, Posner (1980) assumes that a potential offender will take into account the amount and likelihood of a fine into their cost-benefit analysis before deciding to engage in collusion or not.

Different arguments have been put forward that fines are insufficient to deter cartels. Evidence from the US suggests that fines have a poor record in deterring corporate crime and reducing recidivism (Freedberg, Kehoe and Armendariz 2022). The amount of fines is also often capped under law or may be limited by political considerations, such as fear of losing investment. Monetary fines against individuals could be ineffective, as companies could compensate its employees, leaving the risk of imprisonment as the only element of the cost-benefit analysis of potential cartelists that could act as an effective deterrent (UNODC 2020:8-9; Wirz 2016). On the other hand, if the perpetrator of cartel activities has been a manager who does not own the company, then the corporate fine would be inappropriate as it would sanction the owner-shareholder rather than the true perpetrator of the crime (Agrawal 2023).

Others contend that sanctions such as debarment similarly have unintended negative consequences. For example, by excluding illegitimate suppliers through debarment, the government can improve the integrity of the market; however, the more suppliers that they keep out of markets, the less competitive they will be (Auriol, Hjelmeng and Søreide 2017). This leads some to question the benefits associated with debarment (Auriol, Hjelmeng and Søreide 2017).

Given the issues involved with fines and debarment, many increasingly view custodial sentences as a more effective means of deterring individuals engaged in collusion.

Such individuals may fear the repercussions of imprisonment to a greater extent than fines. For example, it was found that, based on available data collected up to 2003, an individual accused of cartel activity in the US had never requested to go to prison in lieu of paying a fine (OECD 2003b cited in Whelan 2014). Similarly, the US Antitrust Division found, after interviews and research, that executives that were actively engaged in cartels in other countries specifically decided not to fix prices in the US to reduce the risk of custodial sentences (Masoudi 2007:10).

White-collar crime is often viewed as a more rational form of criminality, where the risks and rewards are carefully evaluated by potential offenders and potential offenders have much more to lose through sanctions than others (Weisburd, Waring and Chayet 1995). This argument has been echoed by those in the justice sector, with a senior judge in New York arguing, for example, that big fines paid by businesses (or bad publicity) provide no incentive for companies to change and only the threat of prison will be an effective deterrent (Snyder 2017).

In support of the deterrence theory (both specific and general) for custodial sentences, recent research by Huttunen et al. (2022) examined population-level administrative data from Finland from 2000 to 2018 to identify defendants in financial crime cases. These individuals committed crimes such as fraud, business offences, forgery and money laundering (Huttunen et al. 2022:2). To identify the impact of custodial sentences on financial crime defendants, they collected data from the national court registrar which they linked to the administrative defendant records (Huttunen et al. 2022:2).

Using this data, they find that when a financial crime defendant is sent to prison, the probability that they are charged with another crime in the three years post-sentencing decreases by 42.9 percentage points (Huttunen et al. 2022:3). This is twice as large than for other types of non-violent drug and property crimes. The authors argue that this means that the more lenient treatment for financial crime defendants compared to others is difficult to justify on efficiency arguments and reducing recidivism. Moreover, in support of the general deterrence theory, their sentencing reduces their colleagues’ likelihood of committing crime. The authors do note that differences in prison conditions may have affected these results, given that prisons in Nordic countries emphasise rehabilitation and treating inmates equally, whereas other countries tend to treat their inmates differently (Huttunen et al. 2022:39).

Werden, Hammond and Barnett (2011:7) also suggest that the sanction of imprisonment for individuals provides the greatest incentive to self-report through a leniency programme to escape sanctions. Even if full immunity is not possible, the threat of a prison sentence should act as a powerful enough incentive to cooperate with the prosecutor in exchange for a reduction in sentence (Werden, Hammond and Barnett 2011:7)

However, opinions on whether penalties result in deterrence from crimes vary, with some arguing that some – such as custodial sentences – are ineffective deterrents (Commonwealth of Australia 2017). Historically, white-collar criminals have received shorter sentences than ‘street criminals’ (Dutcher n.d.: 1300). Imprisonment, it is argued by some, should be considered as a last resort for non-violent criminals and reserved for recidivists who have indicated that they will not respond to alternative punishments (Commonwealth of Australia 2017:57). One of the reasons for this is that the public do not fear white-collar criminals to the same extent as violent criminals (Duthcer n.d.:1301).

Kleck et al. (2005) conducted interviews with 1,500 residents from 54 counties in the US to test the deterrence theory of more severe punishment levels. They found that respondents’ perceptions of punishment levels and the actual levels of punishment for a crime have no association, undermining the assumptions held in deterrence theories. None of the measures of punishment that they interviewed individuals about (measure of certainty, severity or swiftness of punishment) showed indications of an effect of actual punishment levels on perceived punishment levels (Kleck et al. 2005:747). This does not imply that they do not have a deterrent effect, rather, the level of deterrence is unlikely to increase along with increased levels of severity of the punishment (Kleck et al. 653-654).

UK research shows that there is a correlation between short custodial sentences and higher rates of recidivism, as compared to other penalties such as community orders (Hamilton 2021). Longer term custodial sentences also have lower rates of re-offending, although this may be explained by old age (Hamilton 2021). However, other studies show that there is no significant difference between the rates of re-offending between custodial and non-custodial sentences (Villettaz, Killias and Zoder 2006). Weisburd, Waring and Chayet (1995) also find that custodial sentences did not have a specific deterrent impact on the likelihood of rearrest over a 126-month follow-up period from a sample of 742 offenders convicted in the US.

While the evidence is mixed, there is still a strong argument in the literature for custodial sentences for collusion, particularly given the limitations with fines for companies and individuals and debarment. Nonetheless, the literature is divided on the optimal length of sentences for colluding individuals. An additional consideration is that a lack of custodial sentences in one jurisdiction may have a negative impact on another, given that the evidence suggests that colluding individuals may select a jurisdiction based on how favourable their sanctions are. It is essential for jurisdictions to collaborate to prevent criminals from easily bypassing sanctions in one country by seeking refuge in another.

- For information on red flags in public procurement that may indicate fraud and/or corruption, see the World Bank Group’s resource on Warning signs of fraud and corruption in procurement.

- White collar crime has been defined as ‘illegal acts which are characterised by deceit, concealment, or violation of trust and which are not dependent upon the application or threat of physical force or violence. Individuals and organisations commit these acts to obtain money, property, or services to avoid the payment or loss of money or services or to secure personal or business advantage’ (Federal Bureau of Investigation cited in Dutcher n.d.:1297).

- The more recent OECD Competition Trends reports do not publish this data.

- These have been identified through a desk-based review to provide an overview of different approaches taken by EU member states, rather than an exhaustive list.

- It should be noted that, even in jurisdictions that do not explicitly mention custodial sentences for collusion, they may still be prosecuted under the criminal code for other crimes such as fraud, etc.