Query

Mozambique’s maritime resources have the potential to contribute to economic growth. However, corruption, particularly political corruption and conflicts of interest, have constrained its potential to do so and has put its sustainability in jeopardy due to overexploitation. Please analyse the evolution of the situation with regard to governance and corruption problems in the sector, including to what extent current initiatives, efforts and programmes respond to these problems, and indicate possible needs for further engagement.

Background on Mozambique’s fisheries sector

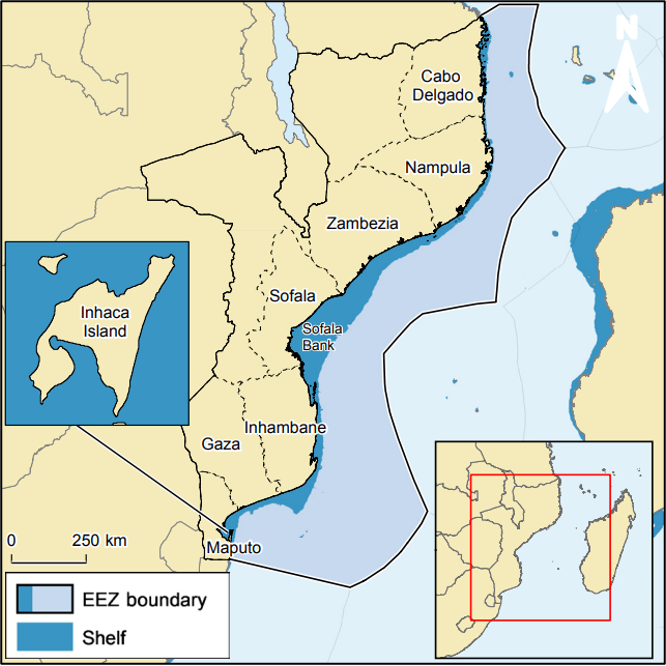

Mozambique in southeast Africa has a coastline facing the Indian Ocean (also known as the Mozambique channel region) stretching over 2,700 kilometres. Its territorial waters and exclusive economic zone – the area of the sea in which it has exclusive rights under international law regarding the use of marine resources such as fish species (as depicted in Figure 1) – constitutes around 587,000 km2 and a rich marine life (FAO 2023).

Figure 1: Map of Mozambique and its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), as well as the extent of the continental shelf (in darker blue).

Sourced from Doherty et al. 2015

Fishing in Mozambican waters has become a vital source of domestic income generation, representing approximately 10.3% of national GDP in 2017 (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a).

This figure aggregates production from industrial fisheries, semi-industrial fisheries and artisanal or small-scale fisheries (FAO 2023). Industrial fishing, which is led mainly by joint ventures between the government of Mozambique and foreign fishing companies, takes place largely in the centrally located Sofala Bank and Maputo regions for coastal shrimp and deep-sea shrimp, as well as the wider channel for migratory species such as tuna; semi-industrial fishing – domestically operated small trawlers – is also mostly carried out in the Sofala Bank and Maputo areas, often with a strong focus on shallow-water shrimp (FAO 2023). Artisanal fishing is carried out widely along the coast, primarily by sole traders and households – two-thirds of the country’s population of around 35 million people reside in the coastal area (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a) – and helps sustain the livelihoods of least 800,000 families (World Bank 2020; Sitoe 2022). Artisanal fishing constitutes around 90% of Mozambique’s total fishery production (FAO 2023). Fishing is also carried out in inland waters, especially for the kapenta fish (Limnothrissa miodon) in the Cahora Bassa reservoir and tilapia (tilapia rendalli) in several reservoirs such as Cahora Bassa and Massingir. Estimates from 2021 indicate around 73% of catches come from the ocean and the remainder from inland waters (FAO 2023).

Nevertheless, in the recent decades, the potential of the fisheries sector has come under threat of overexploitation of fish stocks as well as habitat destruction (FAO 2023). Zeller et al. (2016) found a significant decline in local fish stocks between 1950 and 2016, matched by a depreciating catch rate. FAO (2023) attributes this pattern to overfishing by industrial fleet trawlers and the accelerated expansion of artisanal fisheries, plus the prevalence of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. In 2024, the National Sea Institute (INAMAR) of Mozambique estimated that IUU fishing and related tax evasion causes annual losses of up to US$70 million in Mozambique (360Mozambique 2024a). In recent years, Mozambique's government and international donors have been investing in a Blue Economy approach2f097e0fe85f to revitalise the fisheries sector, which encompasses the creation of jobs and the stimulation of economic growth through the sustainable use of marine resources.

This Helpdesk Answer examines to what extent corruption shapes the state of the fisheries sector in Mozambique and the implications this holds for efforts to revitalise the sector.

Box 1: Fishing in the Cabo Delgado province

Since the discovery of large offshore natural gas reserves in 2010, the development of foreign-owned liquefied natural gas projects in the northern province of Cabo Delgado has resulted in the displacement of farmers and fishermen (FAO 2022: 14). Reports indicate that some fishermen have been relocated far from the coast, while gas drilling operations have affected fish stocks (Meek and Nene 2021).

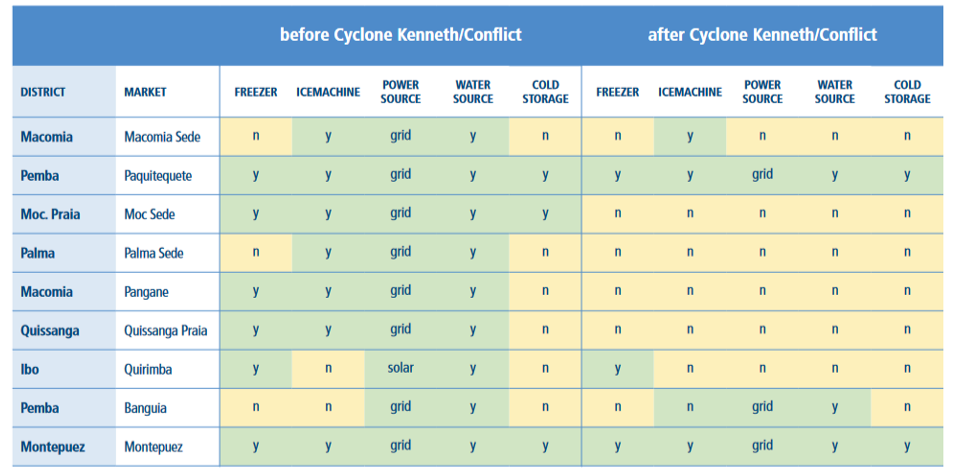

Moreover, fishing in Cabo Delgado province has been severely affected by the conflict that erupted in 2017, and by April 2021 had forced more than 1,000 businesses in the province to close and led to nearly 200,000 jobs being lost (ACAPS 2023: 6). Cyclone Kenneth further exacerbated the situation in April 2019. A 2022 assessment by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations has documented how the combined effect of conflict and cyclone led to widespread destruction of “landing sites, storage and processing facilities, fish markets, roads for accessibility and other relevant services” to the fisheries sector (FAO 2022: 22).

The precise nature of the impact on fishing communities has depended on their location. In areas less affected by conflict such as Ibo island, to which fisherman displaced by fighting in other regions migrated, there has been a reported decrease in the average size of fish landed and lower total catch per fisherman since the outbreak of the conflict, due to increased pressure on fish stocks in those areas (FAO 2022: 14). In those places that had been directly affected by the conflict, including Palma and Quissanga, fishermen reported losing equipment including their vessels and being unable to fish while fighting raged (Ewing-Chow 2023). When people began returning to these areas from late 2021 onwards as the level of violence reduced, fishermen stated that the catches were higher, presumably as fish stocks had recovered and matured during the period in which the fishermen had been displaced by conflict (FAO 2022: 14).

Nonetheless, problems remain, including the fact that the monitoring system of the fishery sector collapsed during the conflict as inspectors and members of local Community Fisheries Councils* fled and data on vessel activity and catches was no longer collected (FAO 2022: 18). Development agencies such as the UN Office for Project Services (UNOPS) have supported fishermen affected by the conflict, including through the provision of fishing supplies and equipment (Lusa 2023).

* Known as CCPs (Conselhos Comunitários de Pesca)

Figure 2: Availability of fishing equipment across Cabo Delgado province before and after Cyclone Kenneth and the conflict

FAO 2022: 16

Key actors

Government and state institutions

The key national authority for the fisheries sector is the Ministry of Fisheries, created in 2000 and renamed the Ministry of the Sea, Inland Waters and Fisheries (MIMAIP) in 2015. The ministry is responsible for developing and implementing the country’s fisheries policies and strategies, in addition to overseeing regulations, planning, licensing and inspection. The MIMAIP has also become responsible for developing and implementing the Blue Economy strategy, which encompasses additional sectors besides fisheries (such as tourism, sea transport, aquaculture and others).

The management of fisheries is largely the responsibility of the National Fisheries Administration (ADNAP) housed at the MIMAIP. The advisory body of the ADNAP is the Fisheries Management Council, which also facilitates the coordination between various entities (Mafuca et al. 2024: 18). The structure of the MIMAIP is currently divided into six thematic directorates: policies and cooperation; sea economy; planification and statistics; human resources; communication and information; and inspection of the sea, inland waters and fisheries. Furthermore, there are nine institutions with administrative autonomy that are under the responsibility of the ministry: Sea National Institute, Development Fund for the Blue Economy, National Institute for Development and Management of Fisheries Infrastructure, Oceanographic Institute of Mozambique, National Fisheries Administration, National Institute for Fisheries and Aquaculture Development, National Institute of Fish Inspection, Sea Museum, and Fishing School.

The efficiency and governance of the MIMAIP has been questioned by some observers. In a 2015 assessment, the International Law and Policy Institute (ILPI 2015: 16-17) highlighted technical and administrative capacities (such as the lack of specialised staff), lack of requisite funding, and political interference as the main challenges state institutions responsible for fisheries faced. A 2023 assessment by the NGO Centro de Integridade Pública (CIP 2023: 35, 51) similarly noted that political appointments and dismissals remain a challenge and that more personnel with operational expertise in the sector were needed.

Political actors

The main political force in Mozambique, the Frelimo party, has played an important role in shaping the fisheries sector, with some of its members facing allegations of political interference. After Mozambique achieved independence in 1975 from Portuguese colonial rule, state-owned enterprises were created to develop the national production and commercialisation of fisheries. With liberal reforms in the 1980s, the state privatised these companies, although reportedly through a process lacking transparency, meaning they were taken over by elites linked to Frelimo (CIP 2023: 26). At the same time, the government stimulated the creation of joint ventures through partnerships between the Mozambican state and foreign fishing companies with expertise and greater financial capacity. These two kinds of companies are still the major ones operating in the industrial fisheries sector (CIP 2023: 6-7).

In general, Frelimo influences the appointment of staff to public institutions, leading to patronage becoming a driving mechanism of the Mozambican political economy, according to Orre and Rønning (2017: 10). Specifically in fisheries, political elites linked to Frelimo reportedly exploit the sector for rent-seeking opportunities by, for example granting quotas and licences to operators who reciprocate their favours or in which they hold an interest (CIP 2023: 25-26). ILPI (2015: 26-27) argues this form of elite capture has been enabled by poor regulation and the lack of controls in the sector.

International actors

Foreign donors have played a key role in the fisheries sector in Mozambique, such as the European Union, Norway, Iceland and Denmark, which has, in turn, influenced policy formulation in the sector (ILPI 2015: 30-31). However, according to ILPI (2015: 30-31), donors have begun to prioritise small-scale fishing and aquaculture projects instead of the industrial and semi-industrial sectors, reportedly due to corruption, the persistence of IUU fishing and suspicions that aid was misappropriated to grant loans to Frelimo members (ILPI 2015: 30-31).

Following the tuna bonds case (described in more detail below), bilateral donors and international institutions reacted by suspending all general budget support to Mozambique. For example, the International Monetary Fund suspended disbursements of emergency loans and its financial programme with the country (England 2016; Cortez et al. 2021: 121). The reduction in donor support caused shocks to the Mozambican economy representing a break in what had been a trajectory of economic growth and positive diplomatic relations (Cortez et al. 2021: 121).

Some multilaterals have subsequently resumed direct budget support, first the EU in 2020, followed by the IMF and World Bank in 2022 (European Commission 2020; Club of Mozambique 2022a; Agenzia Nova 2022). However, it appears that bilateral donors remain wary of providing direct budget support and have focused their financial support on specific programming such as water and sanitation, rural electrification and support to civil society (360Mozambique 2024b; FCDO 2023; Openaid 2024).

Another area that has received continued donor support in recent years is the fisheries sector; for instance, Norway announced an investment of US$4 million for the conservation of the marine ecosystem and investing in the Blue Economy approach (Club of Mozambique 2024).

Fishing actors

Industrial fishing is still mostly carried out by foreign companies and joint ventures with the government of Mozambique. The major operators are companies with foreign capital, particularly Portuguese, Spanish and French, which have acted as important sources of foreign currency revenues in Mozambique (Buur, Tembe & Baloi 2012: 22; Benkenstein 2013: 26); these companies export in large quantities to other nations, especially Japan and Spain (FAO 2023). The largest companies currently active in the industrial fishing sector in Mozambique are Sociedade Industrial de Pesca (SIP), Pescamar, Efripel and Krustamoz, with all of them operating mostly in shrimp fishing (CIP 2023: 28-33).

The semi-industrial fisheries sector is primarily domestic, and its development was prioritised in the fisheries master plan in 1994 to create jobs and spread the wealth of the industry (Buur, Tembe & Baloi 2012: 22).

Approximately 300,000 Mozambicans engage in artisanal or small-scale fisheries (ILPI 2015: 12). Mafuca et al. (2024: 23-24) note that the scale of artisanal fishing makes it more difficult to manage in comparison to the other forms. The artisanal sector is an important pillar of food security for rural populations, but it has increasingly become vulnerable to climate change events and overexploitation of fish stocks (Benkenstein 2013: 44; Mafuca et al. 2024: 24).

Evidence indicates that subsets from all three categories of fishing actors have engaged in IUU fishing in Mozambican waters, which in some cases is enabled by political actors or government and state institutions. IUU fishing also involves other actors, such as local and transnational organised criminal networks (Club of Mozambique 2022b). Ikweli (2021) carried out an investigation in the Angoche region and uncovered evidence that many fishermen were using their boats to traffic hashish to South Africa; they hypothesised this was enabled due to corruption of law enforcement authorities.

Policy and legal frameworks

The most relevant laws and policies regulating the fisheries sector in Mozambique include:

- The Sea Act (1996) defined the general legal framework for the activities taking place in Mozambican waters. The "Law of the Sea" also defined the governmental bodies related to maritime policy.

- The Marine Fisheries’ Regulation (2003) regulates fishing activities, defined fishing types and vessels, established the Fishing Management Commission, and created the first monitoring and inspection procedures.

- The Policy of Monitoring, Control and Surveillance of Fisheries (MSC) (2008) aims to guarantee the sustainable development of fisheries resources, through curbing IUU and establishing a multi-sectoral system of surveillance. The MSC policy is divided into three axes: i) monitoring, including data collection and analysis on catches, vessel locations, fishing zones, ports and others; ii) control, adopting national legal and administrative measures, including terms and conditions of the fishing licence and its implementation; and iii) surveillance, including the supervision of fishing activities and related activities to ensure compliance with oversight measures.

- The National Plan to Prevent, Avoid and Eliminate IUU (2009) sets out a roadmap listing 85 different IUU countermeasures. According to the Environmental Justice Foundation (2024a: 18) the implementation and enforcement of the measures laid out in the national plan has been poor.

- The Fisheries Law (2013) establishes the legal regime for all fishing activities (for national and foreign fishing vessels) and sectors and defined the structure of fisheries management.

- The Fisheries Plan (2010-2019) was related to the action plan for poverty reduction and is focused on improving food security and nutrition in fish for the population, and improving the living conditions of fishers and small-scale fishing communities. An equivalent plan for the 2020s was not adopted.

- The Law for the Protection, Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biological Diversity (2017) establishes six marine protected areas (MPAs) in Mozambican waters under which special conservation measures and fishing restrictions apply (Mafuca et al. 2024: 2).

- The Policy and Strategy of the Sea (2017) consolidated the national strategy for the management of the sea, focusing on developing a blue and sustainable economy, developing responsible fisheries and aquaculture to ensure food security for the population.

- The Law of the Sea (2019) defines the exercise of sovereignty and jurisdiction over the national sea, including regulations on national and foreign vessels.

- The Marine Fisheries’ Regulation (2020) strengthened measures set out in the Fisheries Law (2013) banning, for example, fishing vessels with a history of IUU fishing infractions from flying the Mozambican flag.

- The Regulation for Inland Water Fisheries(2022) regulates fishing activities and related fishing operations carried out in inland waters.

- The Aquaculture Development Strategy (2020-2030)sets out measures to promote the development of aquaculture in a sustainable way, including by addressing fish stock deficits.

- The management plans (2021-2025)for shallow-water shrimp, deep-water crustaceans and rocky bottom demersal fish. These standalone plans define the maximum number of licences, the closed season for the industrial and semi-industrial sectors to protect species, and define which vessels with fishing licences are required to use a vessel monitoring system (VMS) device (Mafuca et al. 2024: 21).

- The Fisheries monitoring, control and surveillance policy (2024) aims to implement an efficient MSC system to counter IUU fishing and to promote sustainable and responsible fishing practices as part of the wider Blue Economy strategy.

Furthermore, Mozambique is a member or signatory of several international agreements, conventions and bodies. For instance, the Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA) which is a binding international agreement to prevent and eliminate IUU fishing, and the Southwest Indian Ocean Fisheries Commission (SWIOFC), which is a regional fisheries advisory body established to promote the sustainable use of marine resources including through curbing IUU fishing.

Mozambique is also a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) under which the Monitoring, Control and Surveillance Coordination Centre (MCSCC)leads regional efforts in Africa to counter IUU fishing. In 2023, the MCSCC began operating in Maputo, the capital of Mozambique, where it operates a regional fishing vessel register and monitoring system andcoordinates information sharing among SADC members (Stop Illegal Fishing 2024).

Blue Economy approach

In Mozambique’s five-year government programme (2020-2024), the main objective of the fisheries sector is described as:

[S]trengthen the development of artisanal fishing and value industrial fishing, in the context of the Blue Economy, as well as the development of aquaculture, creating more employment opportunities for Mozambicans, particularly young people, and directly contributing to improving the quality of life of the population from the perspective of combating hunger, poverty and malnutrition.

This reflects a shift in the fisheries sector to the adoption of a so-called Blue Economy approach, which is also aligned with the broader Agenda 2063 for Africa that holds:

the ocean/Blue Economy shall be a major contributor to continental transformation and growth, through knowledge on marine and aquatic biotechnology, the growth of an Africa-wide shipping industry, the development of sea, river and lake transport and fishing, and exploitation and beneficiation of deep-sea mineral and other resources.

More broadly, it is worth noting that the Blue Economy approach has been subject to critique on several counts. First, Germond-Duret et al. (2022) point to the “ambiguity of the Blue Economy concept and the confusion over its social and environmental sustainability, which can ultimately result in harmful practices.” In this view, the ‘Blue Economy’ terminology can serve as a means of legitimising the unsustainable extraction of maritime resources in a manner that imposes environmental and social costs. Similarly, Schutter et al. (2024) argue that the vague conceptualisation of the Blue Economy means it “risks being co-opted to facilitate further exploitation of ocean spaces and resources without contributing to environmental sustainability or social equity.”

Second, there is a lack of transparency with regard to financial resources allocated by both public and private sector actors to Blue Economy initiatives (Schutter al. 2024). Third, an assessment of Blue Economy approaches in Africa has concluded that weak governance, oversight and monitoring in the maritime sector on the continent is associated with a high risk of Blue Economy initiatives becoming “plagued by the corrupt tendencies of the political elite” and serving “the interests of foreign firms” rather than catering to local development priorities (Akpomera 2020).

In Mozambique, the MIMAIP has expanded its activities and departments to operationalise the Blue Economy, and the Blue Economy Strategy (2024-2033) was recently launched. This strategy intends to mobilise different government sectors, including the Office of the President and aims to promote the sustainable use of ocean resources, improve the living standards of coastal populations, protect the marine ecosystem, while supplying the domestic market and contributing to the national GDP. It recognises that IUU, poor monitoring capacities, pollution and climate change threatens the achievement of these goals (360Mozambique, 2024c). Nevertheless, the strategy does not establish concrete objectives or measures to counter corrupt practices in the fisheries sector.

Despite this, the national government and donors’ recent commitment to revitalising the sector through a Blue Economy approach has opened a window for reform that could potentially help to curb corrupt practices in the fisheries sector. Indeed, in recent years, several initiatives undertaken by the national government as well as regional and international have been developed under this broader approach of the Blue Economy, some of which also include measures to curb IUU and improve the governance of fisheries. These are described in an annex below.

Transparency levels and gaps

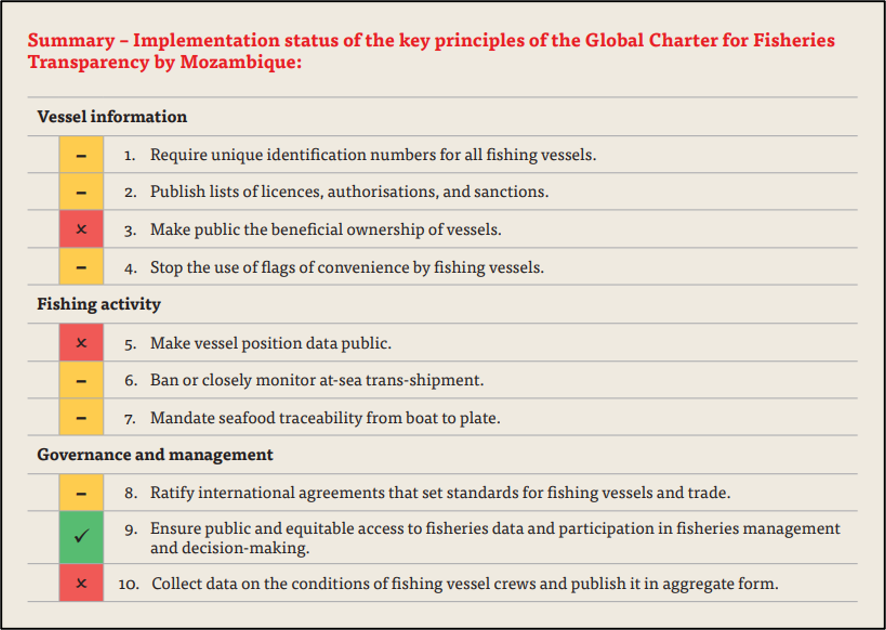

Fisheries value chains are typically long and complex, creating numerous opportunities for corruption (Freitas 2021: 1). Therefore, ensuring transparency at all stages of the fisheries value chain81fe5204aacf is commonly agreed as a significant way of detecting corruption and other forms of malpractice in the sector (Standing 2008: 22). Notwithstanding Mozambique’s legal and policy frameworks, several observers have highlighted the persistence of significant transparency gaps in its fisheries sector. CIP (2023: 22-26) highlights how the allocation of quotas and licences and access to loans and credit for acquiring fishing vessels has historically lacked transparency in Mozambique. The most extensive review undertaken thus far003f444193be has been the Environmental Justice Foundation’s (EJF) 2024 assessment of Mozambique’s implementation of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency.

Figure 3: Environmental Justice Foundation’s 2024 assessment of Mozambique’s implementation of the ten key principles of the Global Charter for Fisheries Transparency

Sourced from Environmental Justice Foundation (2024a: 18). A red cross indicates a principle of the Charter that has not been implemented, an orange dash indicates a principle that has been partially implemented and a green tick indicates a principle that has been successfully implemented.

Assessing the charter’s ten principles, it found that Mozambique had failed to implement three, had partially implemented six and had successfully implemented one (see Figure 3).

For principle 1, requiring unique identification number for all fishing vessels, EJF found that Mozambique had implemented a unique identification scheme, but this had not been made publicly available; furthermore, it flagged that having such a number was not required for vessels when applying for a licence (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 19).

For principle 2, requiring the publishing lists of licences, authorisations and sanctions, EJF found that while Mozambican authorities published a list of licences on the ADNAP website, data was often hard to access or was incomplete; furthermore, a list of sanctioned vessels did not appear to be available (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 19).

For principle 3, on publicising the beneficial ownership of vessels, it was found declaring beneficial ownership is not a requirement under Mozambican law and therefore no such database exists (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 20).

For principle 4, on stopping the use of flags of convenience51b30dc39b8b by fishing vessels, the Environmental Justice Foundation (2024a: 20) found that there was a registration process in place for vessels to be able to fly the Mozambican flag. However, they also concluded there is no legislation in place that prevents foreign vessels using flags of convenience from obtaining licences to operate in Mozambican waters.

For principle 5, on making vessel position data public, it was found that while industrial and semi-industrial fishing vessels are legally required to use a vessel monitoring system (VMS)88884f3ea349 (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 20), enforcement was poor, and the existing data was not made public (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 20).

For principle 6, on banning or closely monitoring at-sea trans-shipment,97ae310842fb it was found that while this was prohibited within Mozambican jurisdictional waters, certain checks such as reporting obligations were insufficient (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 47).

For principle 7, on mandating seafood traceability from boat to plate, EFJ assessed that Mozambican law requires vessels to use electronic catch reporting systems or use other forms of reporting, but this was insufficient to ensure full traceability (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 20).

For principle 8, on ratifying international agreements that set standards for fishing vessels and trade, it noted Mozambique was party to the 2009 Agreement on Port State Measures which targets IUU fishing, but highlighted it had not yet signed up to other relevant International Labour Organisation (ILO) treaties (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 21).

For principle 9, on ensuring public and equitable access to fisheries data and participation in fisheries management and decision-making, EJF found that relevant data was generally available on the MIMAIP and ADNAP websites, and that the 2020 regulation had introduced participatory mechanisms to the sector such as the formalisation of community fishing councils.

For principle 10, oncollecting data on the conditions of fishing vessel crews and publishing it in aggregate form, EJF assessed that this was not required under Mozambican law and nor was it publicly available (Environmental Justice Foundation 2024a: 21).

Corruption risks in Mozambique’s fisheries sector

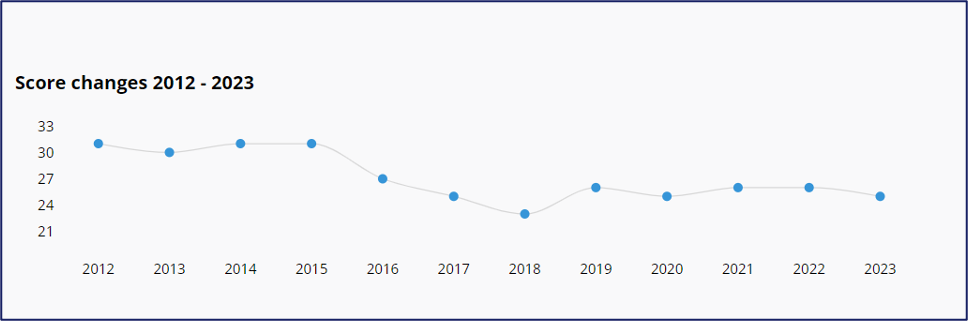

In general, available survey data suggests there is a medium-to-high prevalence of corruption in Mozambique. Its 2023 corruption perceptions index (CPI) score was 25/100, ranking it 145 out of 180 countries measured; this score has remained largely stagnant in recent years (see Figure 4). Furthermore, the 2019 Global Corruption Barometer found 35%t of public service users had paid a bribe in the previous 12 months to being surveyed (Transparency International 2019).

Figure 4: evolution of Mozambique’s CPI scores between 2012-2013

Sourced from Transparency International n.d.

There is no equivalent survey data specifically for the fisheries sector in the country, but cases and anecdotal evidence indicates that it is affected by corruption. This section describes corruption risks that are pronounced across fisheries value chains more generally, but also highlights where evidence points to these being present in Mozambique specifically.

Box 2: Corruption risks across the fishing value chain

In many countries, corruption in legal and illegal fishing takes different forms such as bribes, favouritism, conflicts of interests and undue influence (Martini 2013, 4). The fishing value chain can be divided into five main stages, each of them presenting different risks and opportunities for corruption. Camacho (2021: 4-6) defines the types of corruption that can arise in each of these stages.

- Stage 1: Preparation: bribes, illegal payments and conflicts of interests can affect processes which take place before vessels depart, such as licensing and registration.

- Stage 2: Fishing: falsification of records, bribes to inspectors and forced labour can be enablers of IUU.

- Stage 3: Landing: bribing inspectors and falsification of records can ensure illegal catches are not detected when vessels land in ports.

- Stage 4: Processing: the processing of fish products may also bring opportunities for bribes to officials to overlook irregularities, unreported catches or the falsification of data.

- Stage 5: Sales: sales and exports can also be vulnerable to bribery and other forms of corruption to enable the falsification of documents, trade misinvoicing, money laundering and tax evasion.

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing

One of the main ways corruption is linked to the fisheries sector is as an enabler of IUU fishing. IUU encompasses illegal fishing – such as fishing without the authorisation of the state which has jurisdiction over the waters, unreported fishing – such as misreporting details about catches – and unregulated fishing, for example, fishing in areas where there are no applicable conservation or management measures (FAO n.d.).bb63db992fa1

It is estimated that Mozambique loses around US$70 million annually as a result of IUU (Cossa 2023). In contrast, these losses were estimated at $US35 million in 2016, which signifies an increase in IUU activity in recent years (Biermann 2016). The analyst Moisés Mabunda has argued that IUU in Mozambique could not be resolved unless corruption was targeted, especially collusion between Mozambican authorities and foreign fishing actors (Miguel 2020).

This corruption often takes the form of payment of bribes by vessel operators to supervisory authorities in exchange for operating illegally, avoiding punishment, falsifying documents and licences, and using illegal gear (such as gill nets, fish and crab traps, set lines or springers, and others), methods and fishing techniques (Martini 2013: 1). Studies have found that low governance capacity and corruption in the sector are correlated with cases of IUU fishing (Agnew et al. 2009; Österblom et al. 2010).

Witbooi et al. (2020: 19) found that the main reasons for poor enforcement against IUU fishing include low resourcing of law enforcement agencies, lack of coordination between agencies (nationally and internationally), inadequate legislative frameworks and disputes over jurisdiction at sea and extraterritorial jurisdiction. Zeller et al. (2016) found that African countries are often particularly vulnerable to IUU fishing due to the absence of agreements for foreign fleets, the fact that the catch is often not landed or processed in the host country. Another factor relates to shortcomings in monitoring and enforcement of IUUs, which has long been considered weak in Mozambique (Standing 2008: 15). The areal size of Mozambican waters creates inherent surveillance challenges. For example, its coastline hosts an estimated 600 landing sites (Siebels 2020: 41). Furthermore, Mozambique has been historically reliant on other countries such as Tanzania to protect vessels travelling in its waters, especially from the threat of Somali piracy.

Other than detecting the illegal fishing practices, issuing and collecting fines can also pose a challenge. For instance, the Spanish vessel Txoi Argi was fined for fishing without a licence in Mozambican waters and received a fine of around US$ 1 million. According to Fish-i-Africa (2017: 7), this amount was not paid and after negotiations it was reduced to a fine of US$700,000. Cases such as this may point to the inability of national authorities to enforce rules in the sector and impose penalties on industry players.

Abuse of power by enforcement authorities

National enforcement authorities responsible for enforcing fisheries regulations, such as licensing or inspecting, may abuse their power to solicit bribes or other benefits. This can have a downstream effect on others’ conduct in the sector. Sundström (2012) has shown from a local experiment in South Africa that small-scale fishers’ perception of how corrupt the enforcing authority was affecting their willingness to comply with regulations, with the findings holding for both grand and petty corruption.

Decisions about licensing are often the responsibility of a single person, which increases the opportunities of corruption (Standing 2008: 18). In 2017, local authorities from Moma were investigated on suspicion of threatening to withhold authorisation for fishing firms not willing to pay bribes to them (Verdade 2017). In 2018, heads of an inspection team were accused of being involved in a corruption scheme related to fishing of the kapenta fish (Limnothrissa miodon) in the Cahora Bassa reservoir. They were suspected of receiving payments to allow illegal operators from other countries in the Great Lakes region to fish in the reservoir, as well as to invalidate fines which had previously been imposed on these operators (Iva 2018).

The Maritime Anti-Corruption Network (MACN) collects incident reports on port integrity; data from 2011 to 2024 suggests, based on 200 anonymised reports, that at least 177 incidents of bribery and facilitation payments took place in the ports of Mozambique, often at the point of vessel clearance. However, it should be stressed that this sample is not representative and many of the cases pertained to vessels not engaged in fisheries, but other activities (for example, cigarette trafficking).

Box 3: Mangroves

Mangroves are trees and shrubs adapted to growing in transitional coastal habitats in tropical and subtropical regions. These trees act as critical habitats for fish and crustaceans (Carrasquilla-Henao et al. 2019), and they therefore play a key role in maintaining fish stocks. Mozambique has around 12% of Africa’s mangroves, and in 2024 the continent’s largest mangrove restoration project was approved, promising 200 million trees to be planted over 60 years (Barron’s 2024).

There is some evidence linking mangrove destruction to the abuse of power of authorities responsible for licensing. The Maputo Municipal Council reportedly granted a construction licence for a housing project in the mangrove area of Costa do Sol despite it contravening environmental law; the licence was later revoked by the Mozambican attorney general’s office (Club of Mozambique 2023). In another case, police arrested five people in Beira for damaging mangrove forests and fishing for prawns during the closed season, including a police officer who was reported to have ‘authorised’ the crimes of the others (AllAfrica 2018).

The FAO (2022: 19) has noted that some local Community Fisheries Councils, known as CCPs (Conselhos Comunitários de Pesca) are involved in the restoration of mangrove forests in Mozambique, but that in other areas local communities damage the mangroves by harvesting wood from them.

Conflicts of interest

Private interests from fishing companies, political and/or foreign actors can sometimes influence policy decisions in opposition to the public interest. Conflicts of interests arise in cases when politically connected people have direct financial interests in commercial fishing ventures, often being the local partners in joint venture companies, or even when they act as licence holders who charter foreign vessels to fish on their behalf, or even by acting as local agents for foreign fishing companies (Standing 2017). In such cases, governments may unduly advantage the interests of foreign and commercial actors at the expense of their own welfare (Standing 2008, 16).

Conflicts of interest and undue influence in Mozambique’s fisheries has historical roots. During the structural adjustment programmes in the 1990s, Frelimo party members benefitted from privatisation and access to licences and quotas; for instance, former president Armando Guebuza and senior military officials are reported to have taken ownership of joint venture shrimp fishing companies. This reportedly led quotas for shrimp to be set at unsustainably high levels, as well as the decision to restrict the allocation of fishing rights to a few large firms (Buur, Tembe & Baloi 2012; Standing 2017).

Furthermore, as a group of top state and Frelimo party officials received shares in many of the privatised companies, they subsequently participated in their management (Buur, Tembe & Baloi 2012: 22-25), often allegedly to serve their own interests. CIP (2023, 30) also highlights the case of former Ministry of Fisheries director Mamad Sulemane who opened three semi-industrial fishing companies and a processing factory to benefit from shrimp quotas he acquired while in government. The family of the current leader of Frelimo and fourth president of Mozambique, Filipe Nyusi, also is reported to own companies in the fisheries sector; his son Florindo Nyusi owned a company called Motil, which reportedly granted its fishing concession to a Chinese company (Pessoa 2020).

Box 4: Chinese vessels

One notable example of a conflict of interest in fisheries occurs when wrongdoings and illegal activities are not denounced because the offender has ties to politicians and/or public officials (Martini 2013, 6).

While state officials have criticised foreign vessels from Russia, Panama and the Seychelles for IUU activity, some commentators have claimed there is a reluctance to do the same for Chinese vessels (Miguel 2020). Standing (2008) describes how Chinese foreign vessels operating in protected areas in Mozambique have historically been rarely sanctioned, possibly due to economic interests and political relations among the two countries.

In recent years, the industrial fishing sector in Mozambique has become more populated by Chinese vessels. For example, it is estimated that at least 60 Chinese vessels (The Economist 2024) entered Mozambican waters between 2017 and 2018. However, the licensing process was not made public, nor was it known to the Fisheries Administration Commission (CAP) (CIP 2023: 18).

The Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF) detected 86 cases of illegal fishing and human rights abuses in Chinese vessels in the Southwest Indian Ocean between 2017 and 2023 (EJF, 2024b). In Mozambique, the EJF interviewed 16 fishers working on Chinese trawlers who reported illegalities, half of whom reported the deliberate capture and/or injury of vulnerable marine fauna.

The tuna bonds case

The ‘tuna bonds’ or ‘hidden debts’ case is arguably the biggest corruption scandal in Mozambique in recent years, having contributed to a debt default and serious economic crisis (CIP 2023: 29). In the early 2010s, a group of bankers, businesspeople, politicians and public servants, from Mozambique and abroad, organised loans totalling US$2.007 billion from the Credit Suisse and VTB banks. The debt was raised with the aim of financing various maritime projects and three new state-owned companies – a tuna fishing fleet and factory, a maritime security company and a ship repair company. For example, the tuna company behind this factory – Empresa Moçambicana de Atum (EMATUM) – received US$850 million. Hanlon (2021) argues that the prevalence of IUU fishing by foreign vessels was one of the justifications for supporting the development of these companies.

The loans were backed by guarantees from the Mozambican state, but this had been done illegally without following required steps, most notably, without disclosing these loans to the parliament as stipulated by the state budget law. It later transpired that a large portion of the US$2.007 billion had been embezzled and used for the self-enrichment of the people involved in the scheme. Furthermore, the Lebanese naval construction company Privinvest – the contractor of the maritime projects and companies – was alleged to have paid at least US$100 million in bribes and kickbacks to senior politicians and Credit Suisse officials (Hanlon 2021). Many state actors were reportedly involved in setting up the companies, including the Ministry of Fisheries, even though not all of those involved benefitted from the bribes (Cortez et al. 2021: 68).

Since the loans were uncovered in 2016, legal proceedings have been taken against many of those culpable in the scheme. In total, 19 people were tried in Mozambique, including the son of former president Armando Guebuza and three senior officials from the state intelligence agency (Serviço de Informações e Segurança do Estado) (Massango 2024a). Of the 19 to stand trial, 11 were convicted (Checo 2022). Former finance minister Manuel Chang was extradited from South Africa to the US to face criminal trial and in 2024 was convicted for having accepted bribes and conspiring to divert funds (Booty and Bamford 2024). Three Credit Suisse bankers also pled guilty to money laundering charges in the US and the bank itself agreed to pay a fine of US$475 million as part of a settlement with Swiss, UK and US regulators over the case (Booty and Bamford 2024). Furthermore, Mozambique won a “US$3.1 billion lawsuit” in the UK High Court against Privinvest in relation to the alleged bribes paid in the tuna bond scandal (Tobin 2024).

The tuna bonds case had profound repercussions for Mozambique’s economy and international reputation. From 2013 to 2019, Mozambique was one of the countries whose ratings for the V-Dem governance indicators deteriorated most rapidly, including its corruption score (Cortez et al. 2021: 124). It also had severe impacts on the fisheries sector where it played out, including a dip in investment in the sector (Cortez et al. 2021: 125). Siebels (2020: 38) argues the scandal has held back efforts to improve the maritime security and the patrolling capacity of Mozambique’s fisheries enforcement authorities. However, the Mozambican government has committed a series of reforms such as strengthening the debt record and transparency, reforming state-owned enterprises, and establishing a public investment management system and regulatory framework (World Bank Blogs 2022).

In addition, after Mozambique was placed on the grey list of the Financial Action Task Force for an observation period of two years (2022-2024), a new Anti-Money Laundering / Combating Terrorist Financing Law was passed in August 2023 that replaces the previous legislation (Morais Leitão Legal Circle 2024: 136-139). The new AML/CTF regime requires all ‘obliged entities’ – including both financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions – to conduct customer due diligence to verify the identity of their business partners’ ultimate beneficial owners. The law also prescribes the establishment of an Ultimate Beneficial Owner registry (Morais Leitão Legal Circle 2024: 139). The impact of this new law on the maritime sector is not yet fully clear. However, given that many of the illicit activities that serve as predicate crimes to money laundering occur in coastal areas, such as drug trafficking and smuggling, any coordinated attempt to crack down on these activities under the new legal framework could potentially affect fisheries and IUU fishing.

Indeed, in its 2024 Investment Climate Statement on Mozambique, the US State Department commended Mozambique’s justice sector for increased efforts to hold corruption offenders accountable, citing the tuna bonds case.

Countermeasures

Countering IUU fishing

The risks set out in the previous section suggest there is scope for enhanced efforts to counter IUU fishing in Mozambique. This could include improving the monitoring of foreign fishing vessels in Mozambican waters and ports, increasing traceability of the international fleet and increasing efforts to prosecute companies and individuals that engage in illegal activities (Standing 2017).

The Environmental Justice Foundation (2024a: 21) recommended that IUU fishing could be more effectively tackled in Mozambique if the government closed the transparency gaps identified, such as mandating the beneficial ownership data of vessel owners, making VMS data public and publishing information about all arrests and sanctions imposed on individuals and companies for IUU fishing activities. Orofino et al. (2023: 685) recommend widening the adoption of the VMS system or GPS trackers and making VSM data public to enhance accountability. Long (2018) describes how Mozambican authorities in cooperation with partners such as Interpol tracked VMS signals from a vessel engaging in the illegal fishing of toothfish, and then intercepted it in Maputo.

The role of multistakeholder partnerships in curbing IUU fishing has also been stressed. For example, in Tanzania, the Multi-agency Task Team on Environmental and Wildlife Crime (MATT) involves different ministries to coordinate efforts and resources to target environmental and fisheries crime (Witbooi et al. 2020: 20). Furthermore, Witbooi et al. (2020: 20), stress the importance of international cooperation for the investigation and the prosecution of offenders by, for example, requesting support from Interpol and multilateral teams of experts to facilitate information sharing and analysis across jurisdictions. There may also be a role for civil society organisations such as Stop Illegal Fishing who supported the inspection of fishing vessels in Maputo (Stop Illegal Fishing 2020) during the Covid-19 pandemic by piloting body cameras on inspectors to facilitate remote inspections.

Notwithstanding its importance, Standing (2015: 18-19) emphasises that the traditional law enforcement approach has its limitations and should be implemented with other social measures. For example, in some cases artisanal fishers engage in IUU fishing as a survival mechanism, leading CIP to argue that efforts against IUU fishing should be undertaken in tandem with measures targeting poverty and supporting the diversification of economic income opportunities (CIP 2023: 59-50).

Governance and anti-corruption

State actors and public servants’ engagement in corruption is an important enabler of IUU fishing, but it also leads to mismanagement of the fisheries sector.

In this sense, strengthening anti-corruption policies and governance of supervisory actors is an important measure. Some corruption risks in fisheries can be overcome by closer monitoring, setting effective benchmarks and stakeholder engagement (IDLP 2015: 48). Stop Illegal Fishing implemented a project in Mozambique in which frontline fisheries inspectors were equipped with body cameras; this was found to be effective in reducing opportunities for corruption (Stop Illegal Fish 2021: 2). UNODC (2019: 53) also highlights the importance of creating a whistleblowing policy, publishing rules and regulations and increasing digitalisation as important anti-corruption measures for the sector. Furthermore, it recommends enhanced awareness raising for a range of stakeholders about the risks and effects of corruption in the fisheries sector, what they could do to help prevent it, along with increased availability of information to foster a zero-tolerance approach to corruption (UNODC 2019: 45).

In terms of addressing the political corruption and conflict of interest risks Mozambique faces, continuing the trend set by the tuna bonds case and holding offenders accountable is an important step, as well as integrating meritocratic recruitment processes into key bodies such as MIMAIP (CIP 2023). Promoting a greater level of participatory governance in fisheries can also mitigate the potential for conflicts of interests and avoid regulatory and policy capture by politically tied individuals. In Mozambique, civil society oversight of MIMAIP and other bodies relevant to the fisheries industry could help to enhance transparency and guarantee that multiple interests are represented in decision-making (Standing 2017).

Annex

This annex includes a non-exhaustive list of concluded and ongoing initiatives undertaken in Mozambique that align with a Blue Economy approach. These initiatives are naturally multifaceted, but for the purposes of this paper, components relating to IUU fishing and the governance of fisheries are highlighted:

- A World Wildlife Fund implemented project funded by the Blue Action Fund for Marine Protection (2018-2023) recognised the impact of illegal and unsustainable fishing in Mozambique and aimed to support monitoring, control and enforcement to prevent these illegal practices, as well as managing the marine protected areas (MPAs) of Mozambique.

- The World Bank’s Pro-blue Programme (2019) develops activities related to the sea (tourism, renewable energy, maritime transportation) in Mozambique. Relevant initiatives for fisheries included:

- The South West Indian Ocean Fisheries Governance and Shared Growth Programme (SWIOFish) (2015-2021) which brought together different countries of the South West Indian Ocean to develop sustainable practices of fisheries, improve governance and increase the contribution of fisheries to the economy. Upon the project’s conclusion, Mozambique was considered to have achieved the project’s governance indicators by developing and improving management plans and fisheries policies or legal instruments.

- The Artisanal Fisheries and Climate Change (FishCC) (2015-2019) aimed to improve the livelihoods of poor fishing communities through rights based fisheries management and the development of co-management plans for fisheries.

- More Sustainable Fish (2015-2021) also focused on small-scale fisheries, providing support through financial subsidies to artisanal fishing, aquaculture and blue business. A second phase was launched in 2022.

- Fish-i-Africa was a regional project involving eight Eastern African countries led by Stop Illegal Fishing from 2012 until 2020. These countries participated in a task force that enabled the sharing of intelligence on fishing vessels to counter IUU fishing. The task force resulted in nearly US$3 million being collected in fines (Ssemakula 2019). The eight countries continue to cooperate through the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Monitoring, Control and Surveillance Coordination Centre (MCSCC) (Stop Illegal Fishing 2019).

- Lusophone Countries Cooperation to Fight IUU is an ongoing initiative led by Stop Illegal Fishing that promotes the exchange of experiences, identifies common needs, awareness raising and commitment to curb IUU fishing in nine Portuguese speaking countries including Mozambique.

- The International Fund for Agricultural Development(IFAD)’s PRODAPE (2019-2026) project aims to increase the production and consumption of aquaculture products to contribute to poverty reduction and food security among rural households (IFAD 2021).

- The Pro-Peixe (2023-2030) policy supported by IFAD focuses on promoting sustainable fishing practices among artisanal fisheries in coastal communities that are more vulnerable to extreme climate conditions.

- Various definitions of the blue economy have been collected by the United Nations and are available at: https://www.un.org/regularprocess/sites/www.un.org.regularprocess/files/rok_part_2.pdf.

- It should be noted that the Fisheries Transparency Initiative (n.d.) has publicised its intention to carry out an assessment of Mozambique during 2024/2025, but at the point of publication, this has not yet been released. The FiTI Standard is a framework that lists 39 types of information which governments should make transparent, divided into 12 themes such as beneficial ownership, labour standards, law enforcement, subsidies and access agreements.

- UNODC (2019) has developed a value chain approach to identify corruption vulnerabilities at each of the seven stages of the chain: preparation, fishing, landing, processing, sales, transit, and consumer.

- A flag of convenience refers to where a vessel flies a national flag different to that where it is owned or registered.

- VMS systems allow vessels to broadcast their geographical position at set intervals.

- At-sea trans-shipment refers to the transfer of cargo, including fish, from one vessel to another while at sea rather than a port.

- The Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) describes in more detail the various activities which may be considered under the umbrella of IUU.